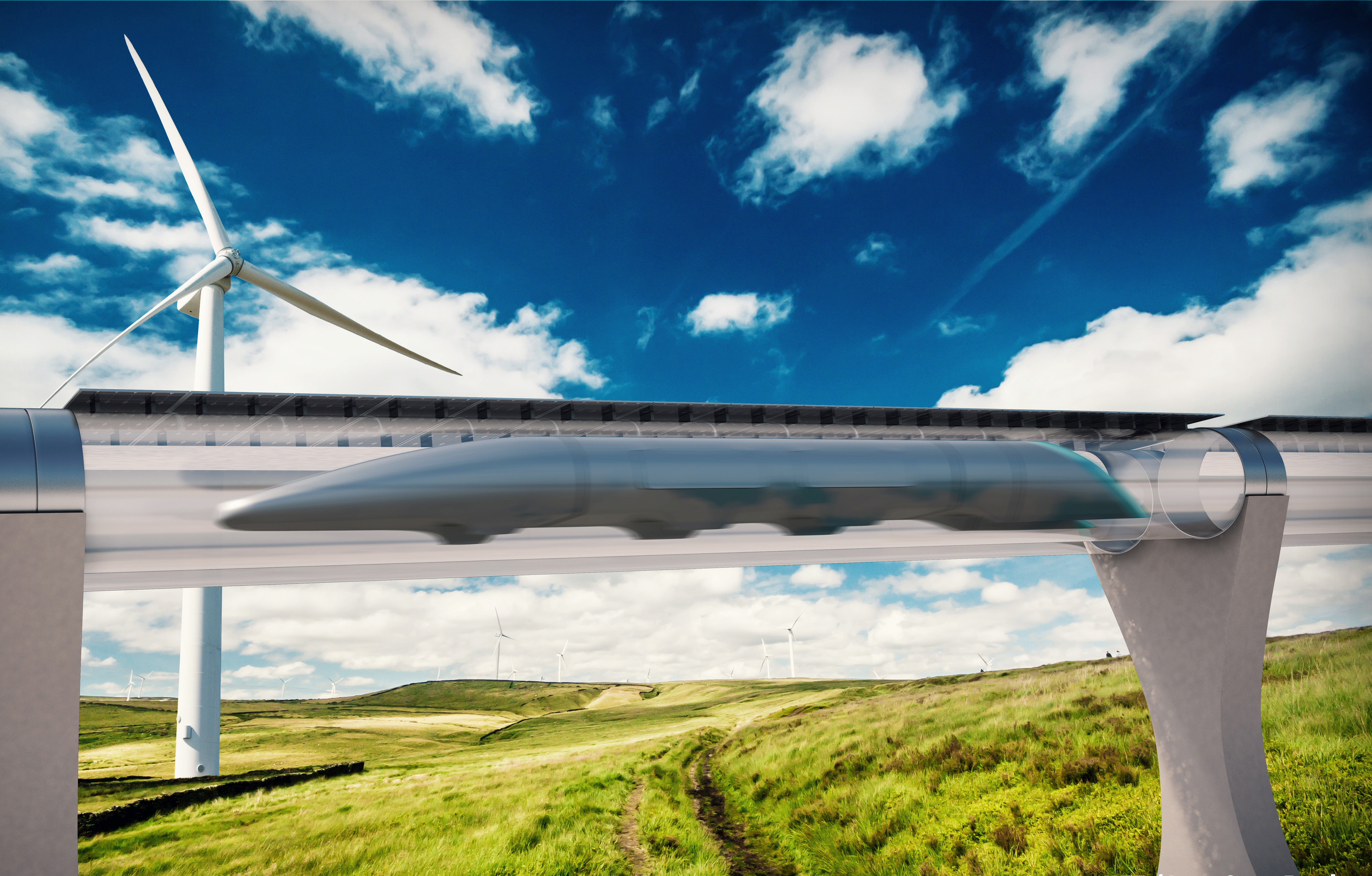

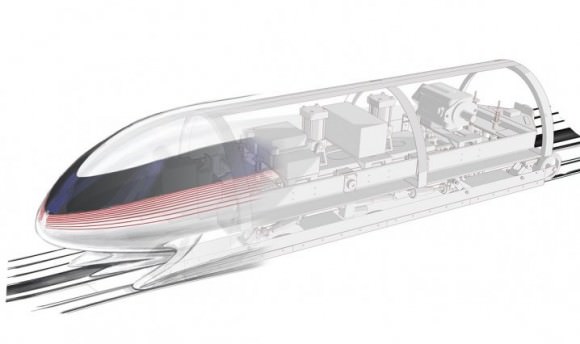

In 2012, SpaceX founder Elon Musk unveiled his idea for what he called the “fifth mode of transportation”. Known as the Hyperloop, his proposal called for the creation of a high-speed mass transit system where aluminum pod cars traveled through a low-pressure steel tube. This system, he claimed, would be able to whisk passengers from San Francisco to Los Angeles in just 35 minutes.

Since that time, many companies have emerged that are dedicated to making this proposal a reality, which include the Los Angeles-based company known as Hyperloop One. Back in 2016, this company launched the Hyperloop One Global Challenge to determine where Hyperloop routes should be built. Earlier this month, the winners of this competition were announced, which included the team recommending a route from Toronto to Montreal.

The Toronto-Montreal team (aka. team HyperCan) was just one of over 2600 teams that registered for the competition, a combination of private companies, engineers, and urban planners. After the field was narrowed down to the 35 strongest proposals, ten finalists were selected. These included team HyperCan, as well as teams from India, Mexico, the UK and the US.

As Rob Lloyd, the CEO of Hyperloop One, said about the competition in a company statement:

“The results of the Hyperloop One Global Challenge far exceeded our expectations. These 10 teams each had their unique strengths in showcasing how they will alleviate serious transportation issues in their regions… Studies like this bring us closer to our goal of implementing three full-scale systems operating by 2021.”

Team HyperCAN was led by AECOM Canada, the Canadian-subsidiary of the multinational engineering firm. For their proposal, they considered how a Hyperloop system would address the transportation needs of Canada’s largest megacity region. This region is part of what is sometimes referred to as the Quebec City-Windsor corridor, which has remained the most densely-populated region in modern Canadian history.

The region that extends from Montreal to Toronto, and includes the nation’s capitol of Ottawa, is by the far the most populated part of this corridor. It is the fourth most populous region in North America, with roughly 1 in 4 Canadians – over 13 million people – living in a region that measures 640 km (400 mi) long. Between the density, urban sprawl, and sheer of volume of business that goes on in this area, traffic congestion is a natural problem.

In fact, traveling from Montreal to Ottawa to Toronto can take a minimum of five hours by car, and the highway connections between them – Highway 417 (the “Queensway”) and Highway 401 – are the busiest in all of Canada. Within the greater metropolitan area of Toronto alone, the average daily traffic on the 401 is about 450,000 vehicles, and this never drops below 20,000 vehicles between urban centers.

In Montreal, the situation is much the same. In an average year, commuters spend an estimated 52 hours stuck in peak hour traffic, which earned the city the dubious distinction of having the worst commute in the country. To make matters worse, it is anticipated that population and urban growth are going to make congestion grow by about 6% in the next few years (by 2020).

Hence why team HyperCAN thinks a Hyperloop network would be ideally suited for this corridor. Not only would it offer commuters an alternative to driving on busy highways, it would also address the current lack of rapid and on-demand mass transport in this region. According to AECOM Canada’s proposal:

“No mode of transportation has existing or planned capacity to accommodate the growth in traffic along this corridor. By moving higher volumes of people in less time, Hyperloop could generate greater returns socially and provide much-needed capacity to accommodate the forecasted growth in demand for travel in the corridor.”

The benefits of such a high-speed transit system are also quite clear. Based on its top projected speeds, a Hyperloop trip between Ottawa and Toronto – which ideally takes about 3 hours by car – could be reduced to 27 minutes. A trip from Montreal to Ottawa could be done in 12 minutes instead of 2 hours, and a trip between Toronto and Montreal could be done in just 39 minutes.

And since the Hyperloop would make its transit from city-center to city-center, it offers something that high-speed rail and air travel do not – on-demand connections between cities. The existence of such a system could therefore attract business, investment, workers and skilled professionals to the region and allow the Toronto-Montreal corridor to gain an advantage in the global economy.

Of course, whenever major projects come up, it’s only a matter of time before the all-important aspect of cost rears its head. However, as Hyperloop One indicated, such a project could benefit from existing infrastructure spending in Canada. Recently, the Trudeau administration created an infrastructure bank that pledged $81.2 billion CAD ($60.8 billion USD) in spending over the next 12 years for public transit, transport/trade corridors, and green infrastructure.

A Hyperloop that connects three of Canada’s largest and most dynamic cities together certainly meets all these criteria. In fact, according to team HyperCAN, green infrastructure would be yet another benefit of a Toronto-Montreal Hyperloop system. As they argued in their proposal, the Hyperloop can be powered by hydro or other renewables and would be 100% emissions-free.

This would be consistent with the Canadian government commitment to reducing carbon emissions by 30% by 2030 (from their 2005 levels). According to figures compiled by Environment and Climate Change Canada, in 2015:

“Canada’s total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions were 722 megatonnes (Mt) of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2 eq). The oil and gas sector was the largest GHG emitter in Canada, accounting for 189 Mt CO2 eq (26% of total emissions), followed closely by the transportation sector, which emitted 173 Mt CO2 eq (24%).”

By allowing commuters to switch to a mass transit system that would reduce the volume of cars traveling between cities, and produces no emissions itself, a Hyperloop would help Canadians meet their reduced-emission goals. Last, but certainly not least, there is the way that such a system would create opportunities for economic growth and cooperation between Canada and the US.

On the other side of the border from the Quebec City-Windsor Corridor, there is the extended urban landscape that includes the cities of Chicago, Detroit, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, Indianaopli, Pittsburgh, and St. Louis. This transnational mega-region, which has over 55 million people living within it, is sometimes referred to as the Great Lakes Megalopolis.

Not only would a Hyperloop connection between two of its northernmost urban centers offer opportunities for cross-border commerce, it would also present the possibility of extending this line down into the US. With a criss-cross pattern of Hyperloops that can whisk people from St. Louis and Pittsburgh to Montreal, business would move at a speed never before seen!

Given the litany of reasons for building a Hyperloop along this corridor, it should come as no surprise that AECOM and team HyperCAN are not alone in proposing that it be built. TransPod Inc, a Toronto-based Hyperloop company, is also interested in constructing Hyperloop lines in countries where aging infrastructure, high-density populations, and a need for new transportation networks coincide.

As Sebastien Gendron, the CEO of TransPod, recently indicated in an interview with Huffington Post Canada, his company hopes to have a Hyperloop up and running in Canada by 2025. He also expressed high-hopes that the public will embrace this new form of transit once its available. “We already travel at that speed with an aircraft and the main difference with our system is we are on the ground,” he said. “And it’s safer to be on the ground than in the air.”

According to Gendron, TransPod is currently engaged in talks with the federal transportation department to ensure safety regulations are in place for when the technology is ready to be implemented. In addition, his company is also bidding for provincial and city support to build a 4 to 10 km (2.5 to 6 mi) track between the cities of Calgary-Edmonton in Alberta, which would connect the roughly 3 million people living there.

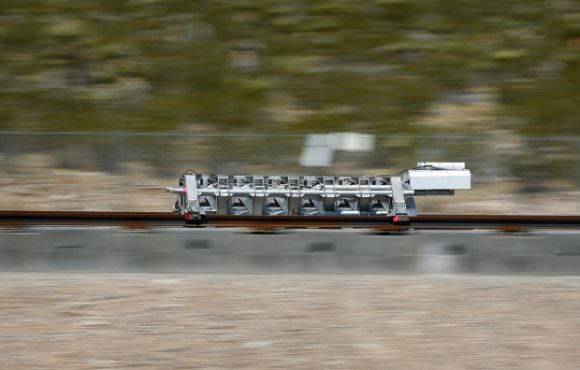

When Musk first unveiled his vision for the Hyperloop, he indicted that he was too busy with other projects to pursue it, but others were free to take a crack at it. In the five years that have followed, several companies have emerged that have been more than happy to oblige him. And Musk, to his credit, has offered support by holding events like Pod Design Competitions and offering the use of his company’s own test track.

And despite misgivings by those who claimed that such a system posed too many technical and engineering challenges – not to mention that the cost would be prohibitive – those who are committing to building Hyperloops remain undeterred. With every passing year, the challenges seem that much more surmountable, and support from the public and private sector is growing.

By the 2020s and 2030s, we could very well be seeing Hyperloops running between major cities in every mega-region in the world. These could include Toronto and Montreal, Boston and New York, Los Angeles and San Fransisco, Moscow and St. Petersburg, Tokyo to Nagoya, Mumbai to New Delhi, Shanghai to Beijing, and London to Edinburgh.

Of course, that’s just for starters!

Further Reading: Hyperloop One, Huffington Post Canada