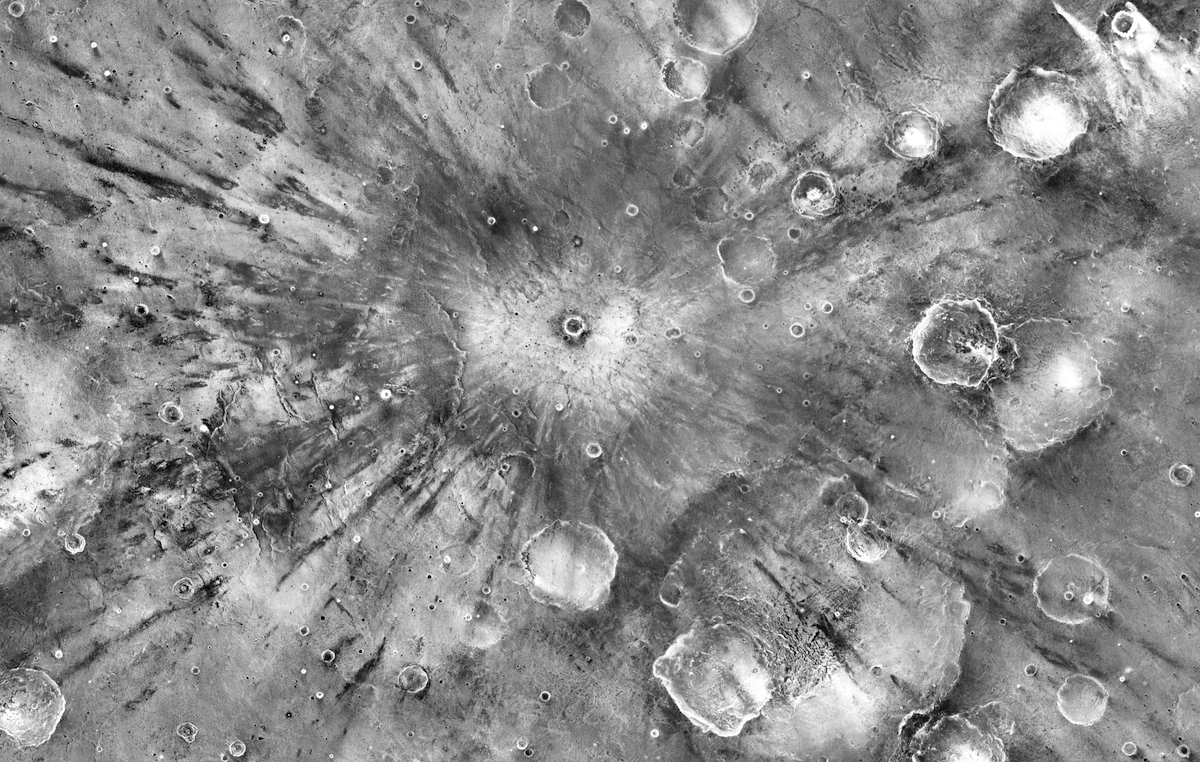

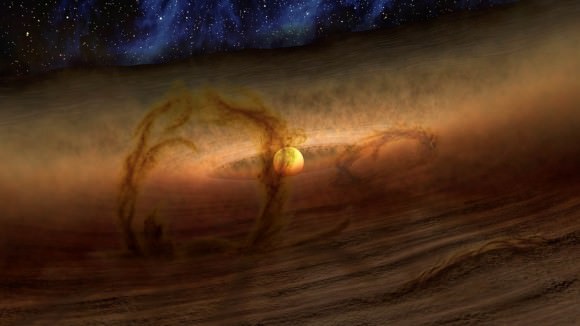

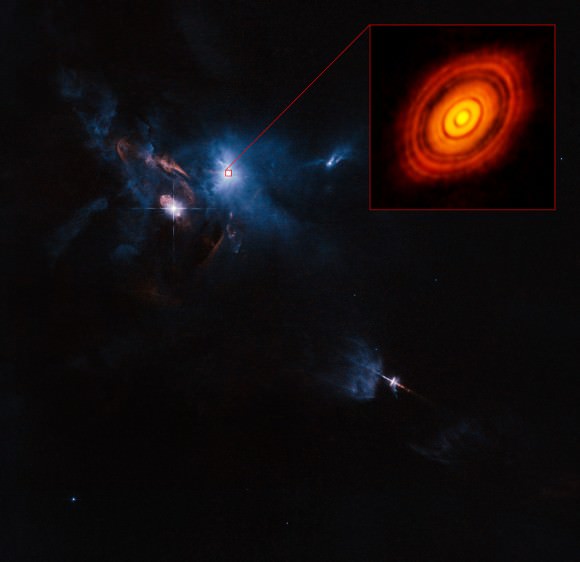

In a test of its new high resolution capabilities, the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) is happily sharing some family snapshots with us. Astronomers manning the cameras have captured one of the best images so far of a newly-forming planet system gathering itself around a recently ignited star. Located about 450 light years from us in the constellation of Taurus, young HL Tau gathers material around it to hatch its planets and fascinate researchers.

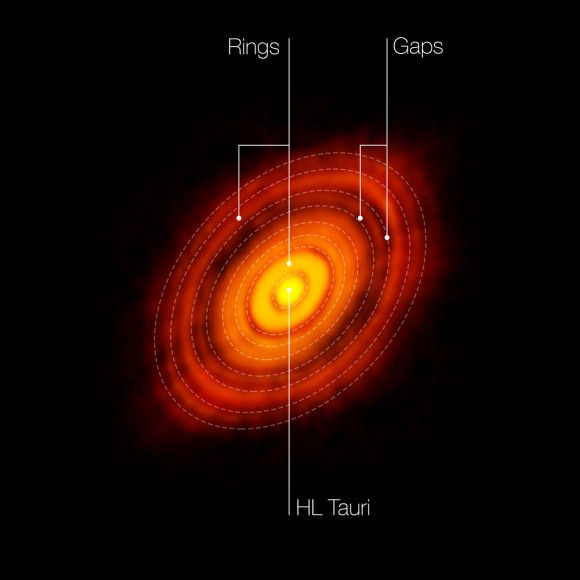

Thanks to ALMA images, scientists have been able to witness stages of planetary formation which have been suspected, but never visually confirmed. This very young star is surrounded by several concentric rings of material which have neatly defined spacings. Is it possible these clearly marked gaps in the solar rubble disc could be where planets have started to gel?

“These features are almost certainly the result of young planet-like bodies that are being formed in the disk. This is surprising since HL Tau is no more than a million years old and such young stars are not expected to have large planetary bodies capable of producing the structures we see in this image,” said ALMA Deputy Director Stuartt Corder.

“When we first saw this image we were astounded at the spectacular level of detail. HL Tauri is no more than a million years old, yet already its disc appears to be full of forming planets. This one image alone will revolutionize theories of planet formation,” explained Catherine Vlahakis, ALMA Deputy Program Scientist and Lead Program Scientist for the ALMA Long Baseline Campaign.

Let’s take a look at what we understand about solar system formation…

Through repeated research, astronomers suspect that all stars are created when clouds of dust and gas succumb to gravity and collapse on themselves. As the star begins to evolve, the dust binds together – turning into “solar system soup” consisting of an array of different sized sand and rocks. This rubble eventually congeals into a thin disc surrounding the parent star and becomes home to newly formed asteroids, comets, and planets. As the planets collect material into themselves, their gravity re-shapes to structure of the disc which formed them. Like dragging a lawn sweeper over fallen leaves, these planets clear a path in their orbit and form gaps. Eventually their progress pulls the gas and dust into an even tighter and more clearly defined structure. Now ALMA has shown us what was once only a computer model. Everything we thought we knew about planetary formation is true and ALMA has proven it.

“This new and unexpected result provides an incredible view of the process of planet formation. Such clarity is essential to understand how our own solar system came to be and how planets form throughout the universe,” said Tony Beasley, director of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) in Charlottesville, Virginia, which manages ALMA operations for astronomers in North America.

“Most of what we know about planet formation today is based on theory. Images with this level of detail have up to now been relegated to computer simulations or artist’s impressions. This high resolution image of HL Tauri demonstrates what ALMA can achieve when it operates in its largest configuration and starts a new era in our exploration of the formation of stars and planets,” says Tim de Zeeuw, Director General of ESO.

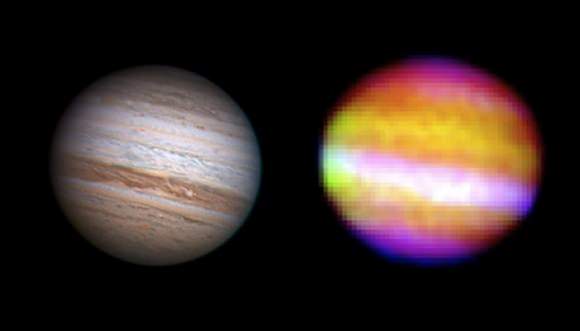

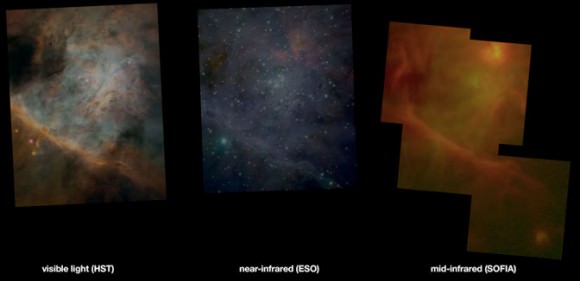

The major reason astronomers have never seen this type of structure before is easy to envision. The very dust which creates the planetary disc around HL Tau also conceals it to visible light. Thanks to ALMA’s ability to “see” at much longer wavelengths, it can image what’s going on at the very heart of the cloud. “This is truly one of the most remarkable images ever seen at these wavelengths. The level of detail is so exquisite that it’s even more impressive than many optical images. The fact that we can see planets being born will help us understand not only how planets form around other stars but also the origin of our own solar system,” said NRAO astronomer Crystal Brogan.

How does ALMA do it? According to the research staff, its new high-resolution capabilities were achieved by spacing the antennas up to 15 kilometers apart. This baseline at millimeter wavelengths enabled a resolution of 35 milliarcseconds, which is equivalent to a penny as seen from more than 110 kilometers away. “Such a resolution can only be achieved with the long baseline capabilities of ALMA and provides astronomers with new information that is impossible to collect with any other facility, including the best optical observatories,” noted ALMA Director Pierre Cox.

The long baselines spell success for the ALMA observations and are a tribute to all the technology and engineering that went into its construction. Future observations at ALMA’s longest possible baseline of 16 kilometers will mean even more detailed images – and an opportunity to further expand our knowledge of the Cosmos and its workings. “This observation illustrates the dramatic and important results that come from NSF supporting world-class instrumentation such as ALMA,” said Fleming Crim, the National Science Foundation assistant director for Mathematical and Physical Sciences. “ALMA is delivering on its enormous potential for revealing the distant universe and is playing a unique and transformational role in astronomy.”

Pass them baby pictures our way, Mama ALMA… We’re delighted to take a look!

Original Story Source: “Revolutionary ALMA Image Reveals Planetary Genesis” – ESO Press Release