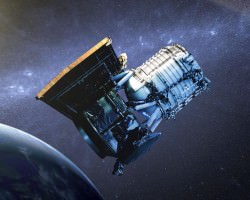

Astronomers wanting a closer look at the recent Type Ia supernova that erupted in M82 back in January are in luck. Thanks to NASA’s Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) near-infrared observations have been made from 43,000 feet — 29,000 feet higher than some of the world’s loftiest ground-based telescopes.

(And, technically, that is closer to M82. If only just a little.)

All sarcasm aside, there really is a benefit from that extra 29,000 feet. Earth’s atmosphere absorbs a lot of wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum, especially in the infrared and sub-millimeter ranges. So in order to best see what’s going on in the Universe in these very active wavelengths, observational instruments have to be placed in very high, dry (and thus also very remote) locations, sent entirely out into space, or, in the case of SOFIA, mounted inside a modified 747 where they can simply be flown above 99% of the atmosphere’s absorptive water vapor.

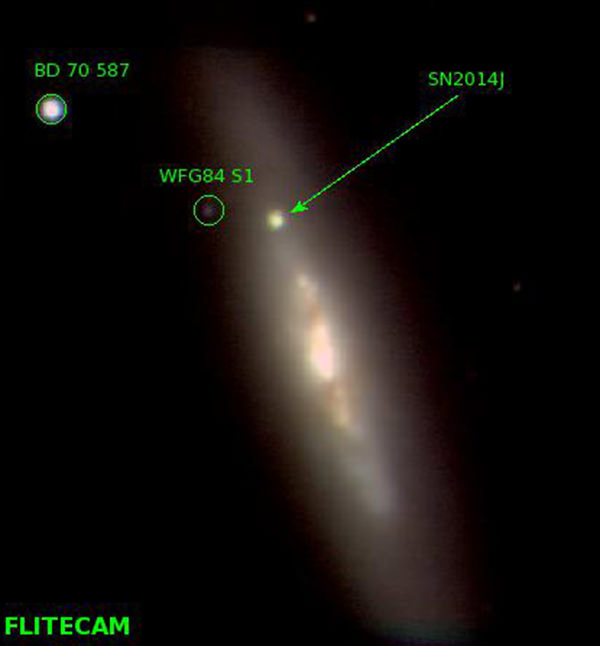

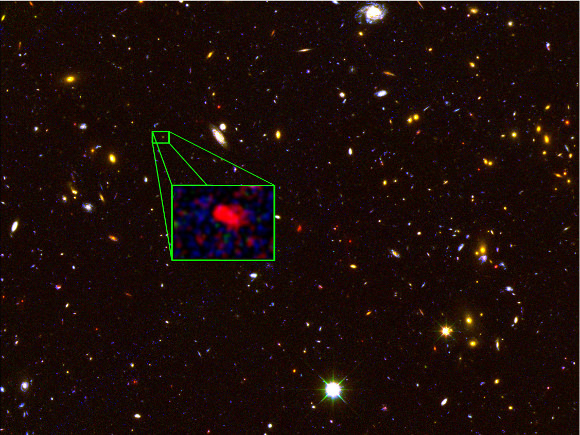

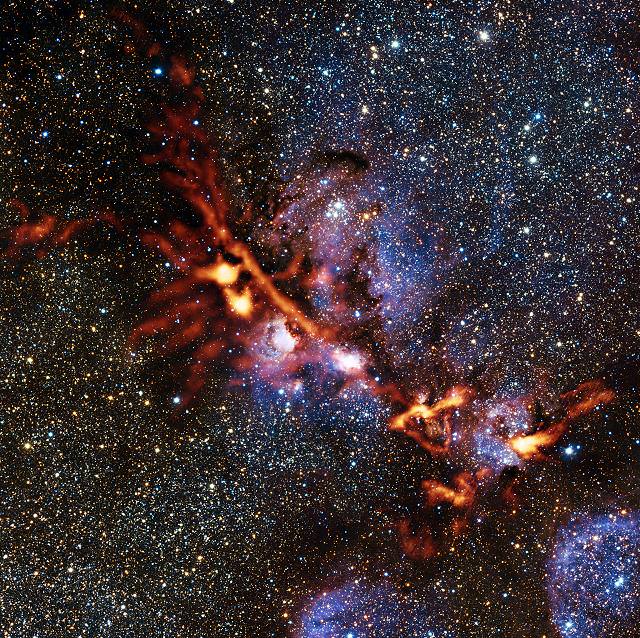

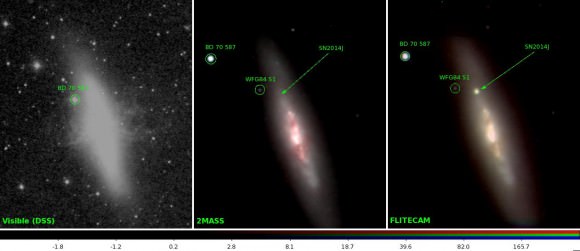

During a recent 10-hour flight over the Pacific, researchers aboard SOFIA turned their attention to SN2014J, one of the closest Type Ia “standard candle” supernovas that have ever been seen. It appeared suddenly in the relatively nearby Cigar Galaxy (M82) in mid-January and has since been an exciting target of observation for scientists and amateur skywatchers alike.

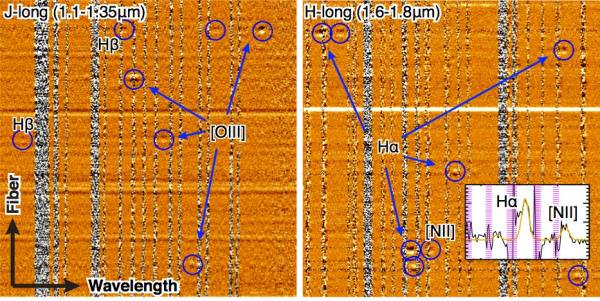

In addition to getting a bird’s-eye-view of a supernova, they used the opportunity to calibrate and test the FLITECAM (First Light Infrared Test Experiment CAMera) instrument, a near infrared camera with spectrographic capabilities mounted onto SOFIA’s 2.5-meter German-built main telescope.

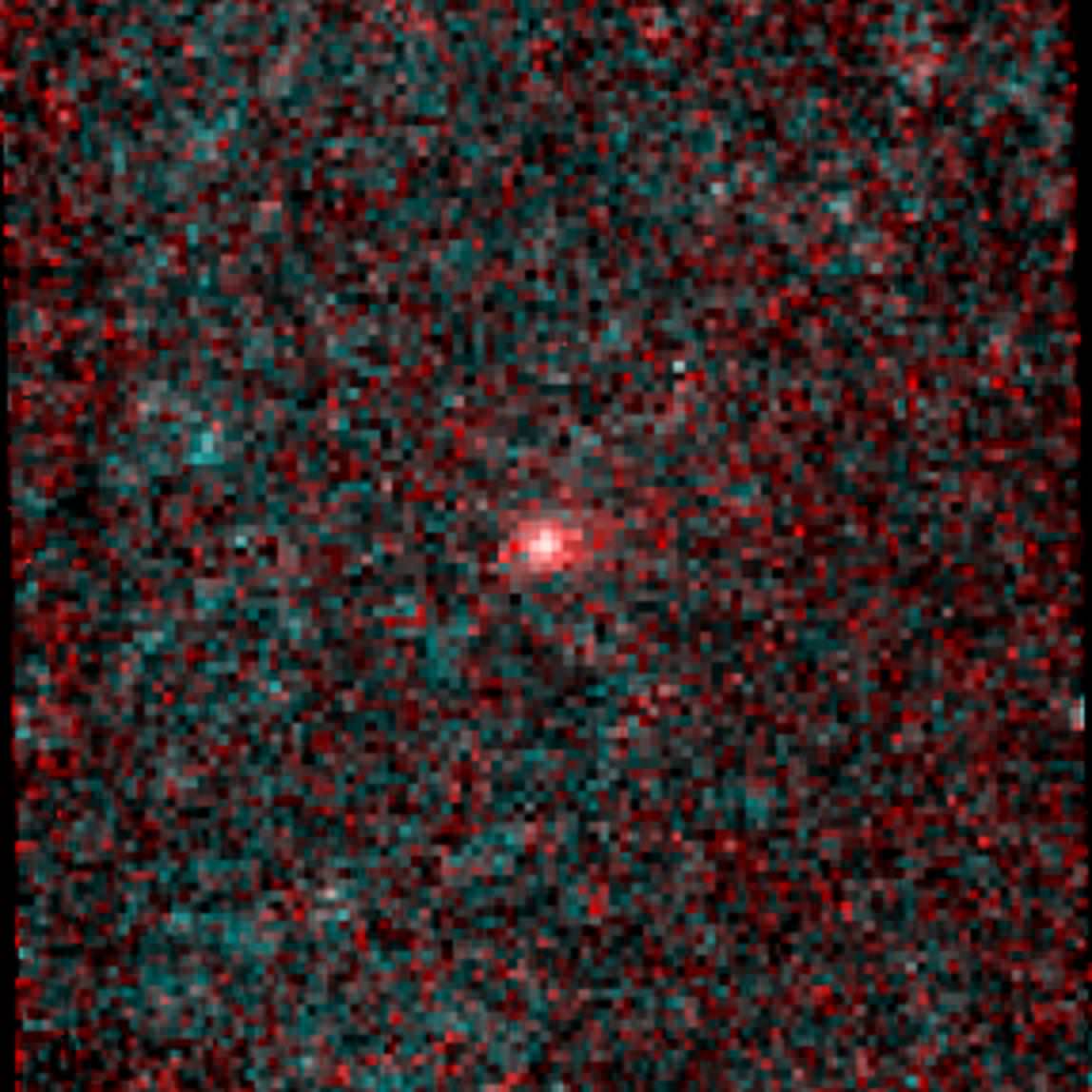

What they’ve found are the light signatures of heavy metals being ejected by the exploding star. (Rock on, SN2014J.)

“When a Type Ia supernova explodes, the densest, hottest region within the core produces nickel 56,” said Howie Marion from the University of Texas at Austin, a co-investigator aboard the flight. “The radioactive decay of nickel-56 through cobalt-56 to iron-56 produces the light we are observing tonight. At this life phase of the supernova, about one month after we first saw the explosion, the H- and K-band spectra are dominated by lines of ionized cobalt. We plan to study the spectral features produced by these lines over a period of time and see how they change relative to each other. That will help us define the mass of the radioactive core of the supernova.”

Further observations from SOFIA will help researchers learn more about the evolution of Type Ia supernovas, which in addition to being part of the life cycles of certain binary-pair stars are also valuable tools used by astronomers to determine distances to far-off galaxies.

“To be able to observe the supernova without having to make assumptions about the absorption of the Earth’s atmosphere is great,” said Ian McLean, professor at UCLA and developer of FLITECAM. “You could make these observations from space as well, if there was a suitable infrared spectrograph to make those measurements, but right now there isn’t one. So this observation is something SOFIA can do that is absolutely unique and extremely valuable to the astronomical community.”

Read more in a SOFIA news article by Nicholas Veronico here.

Source: SOFIA Science Center, NASA Ames

UPDATE 4 March 2014: The FY 2015 budget request proposed by the White House will effectively shelf the SOFIA mission, redirecting its funding toward planetary missions like Cassini and an upcoming Europa mission. Unfortunately, SOFIA’s flying days are now numbered, unless German partner DLR increases its contribution. Read more here.