In perhaps the neatest astronomical application of geneology yet, astronomers found 28 “hidden” families of asteroids that could eventually show them how some rocks get into orbits that skirt the Earth’s path in space.

From scanning millions of snapshots of asteroid heat signatures in the infrared, these groups popped out in an all-sky survey of asteroids undertaken by NASA’s orbiting Wide-Field Infrared Survey Explorer. This survey took place in the belt of asteroids between Mars and Jupiter, where most near-Earth objects (NEOs) come from.

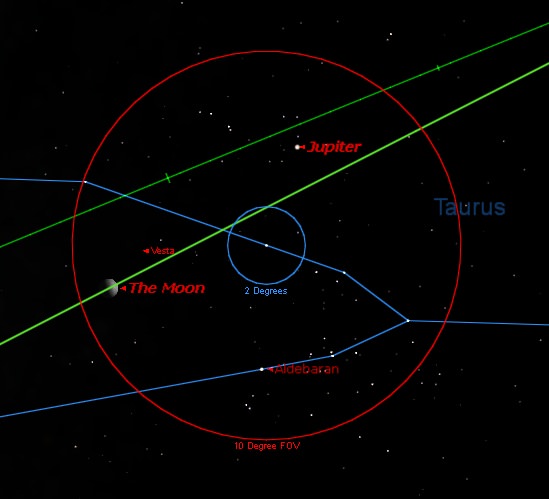

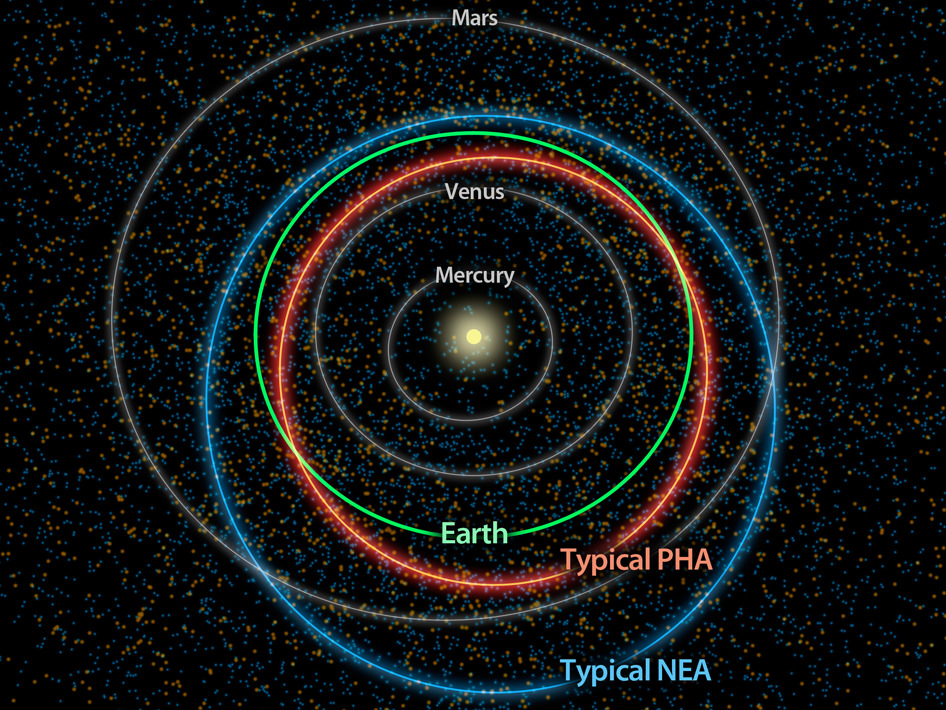

NEOs, to back up for a second, are asteroids and comets that approach Earth’s orbit from within 28 million miles (45 million kilometers). Sometimes, a gravitational push can send a previously unthreatening rock closer to the planet’s direction. The dinosaurs’ extinction roughly 65 million years ago, for example, is widely attributed to a massive rock collision on Earth.

Part of NASA’s job is to keep an eye out for potentially hazardous asteroids and consider approaches to lessen the threat.

There are about 600,000 known asteroids between Mars and Jupiter, and the survey looked at about 120,000 of them. Astronomers then attempted to group some of them into “families”, which are best determined by the mineral composition of an asteroid and how much light it reflects.

While it’s hard to measure reflectivity in visible light — a big, dark asteroid reflects a similar amount of light as a small shiny one — infrared observations are harder to fool. Bigger objects give off more heat.

This allowed astronomers to reclassify some previously studied asteroids (which were previously grouped by their orbits), and come up with 28 new families.

“This will help us trace the NEOs back to their sources and understand how some of them have migrated to orbits hazardous to the Earth,” stated Lindley Johnson, NASA’s program executive for the Near-Earth Object Observation Program.

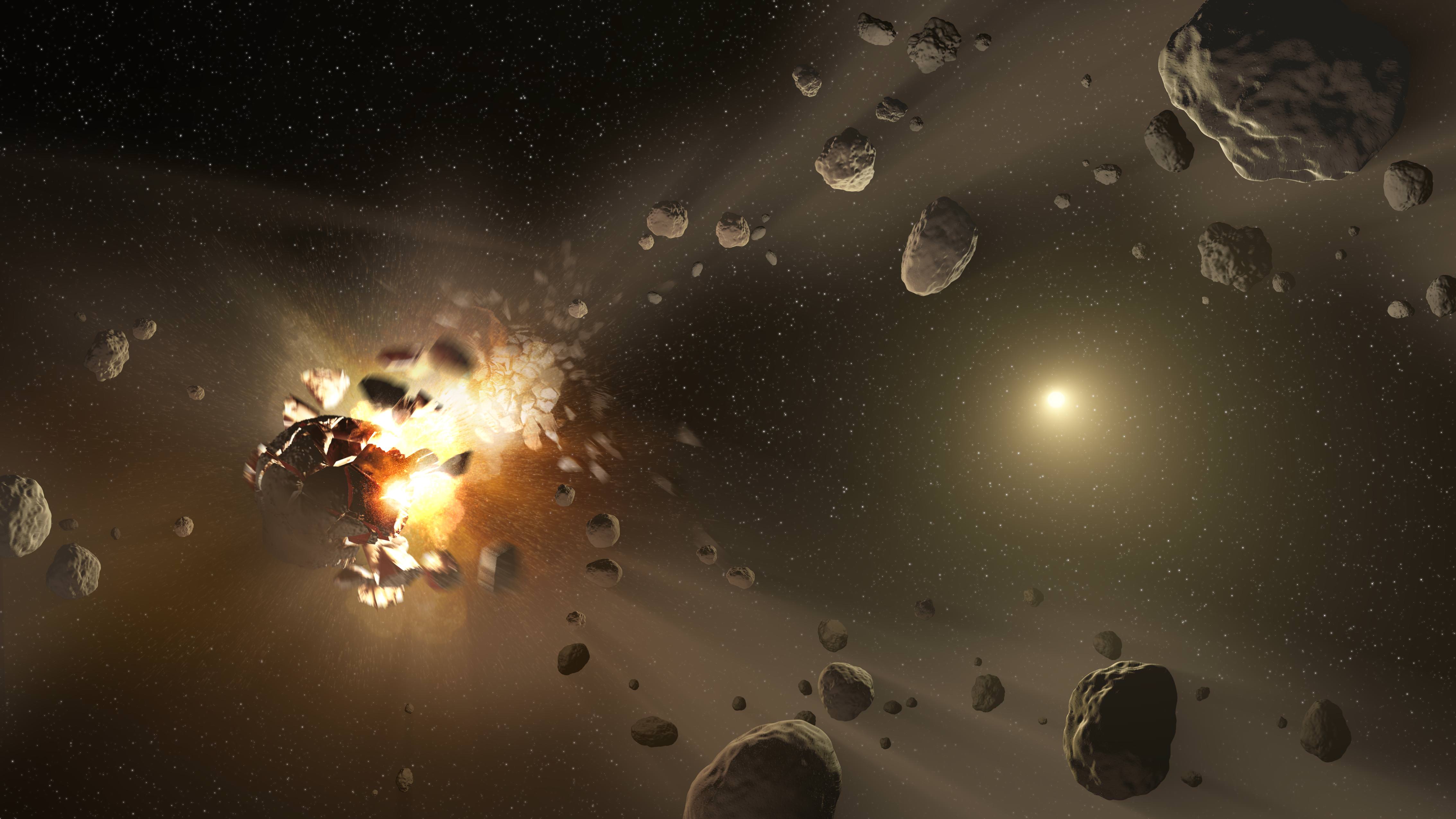

The astronomers next hope to study these different families to figure out their parent bodies. Astronomers believe that many asteroids we see today broke off from something much larger, most likely through a collision at some point in the past.

While Earthlings will be most interested in how NEOs came from these larger bodies and threaten the planet today, astronomers are also interested in learning how the asteroid belt formed and why the rocks did not coalesce into a planet.

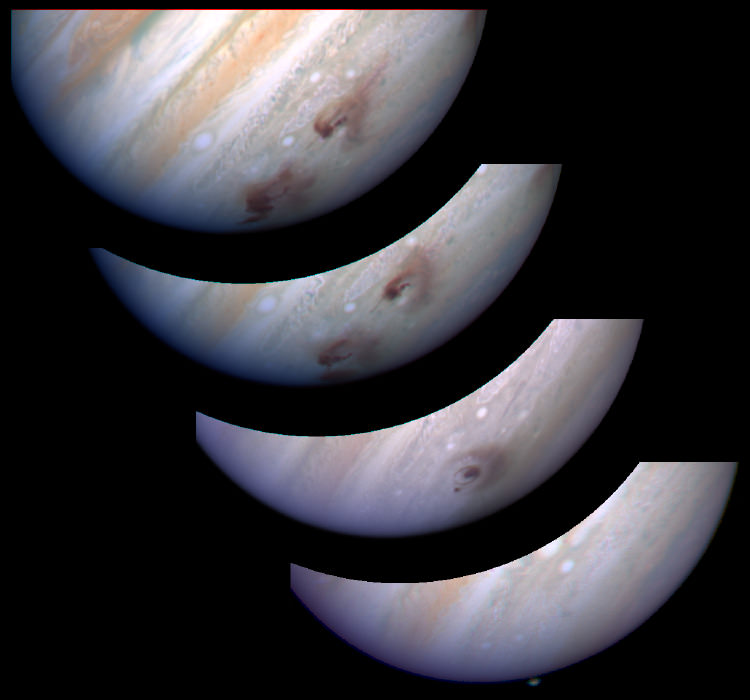

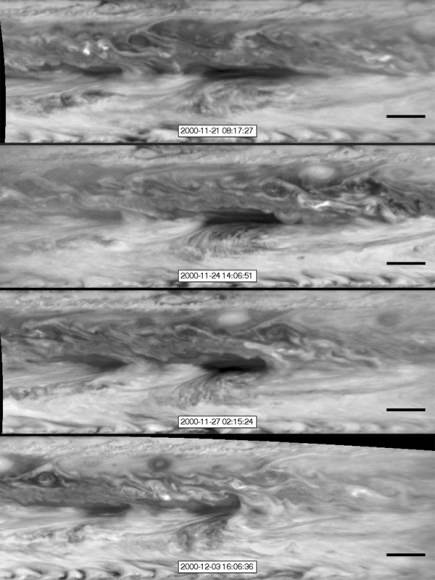

The prevailing theory today says that was due to influences from giant Jupiter’s strong gravity, which to this day pulls many incoming comets and asteroids into different orbits if they swing too close. (Just look at what happened to Shoemaker-Levy 9 in 1994, for example.)

Source: NASA