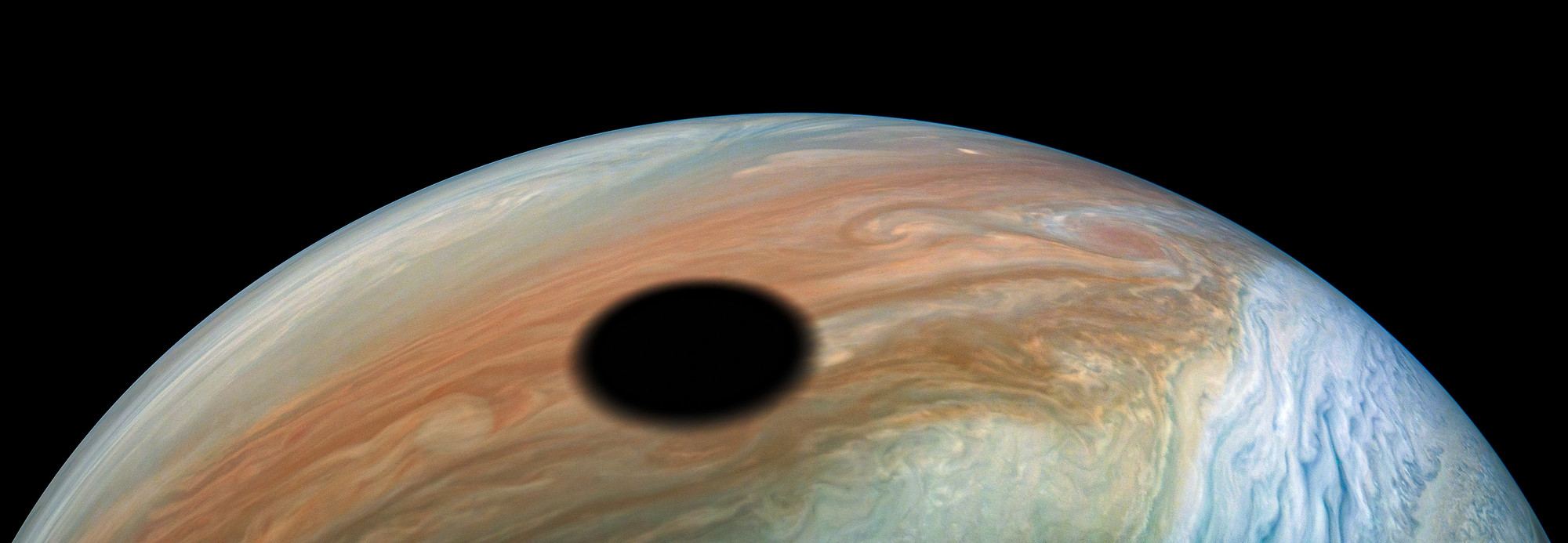

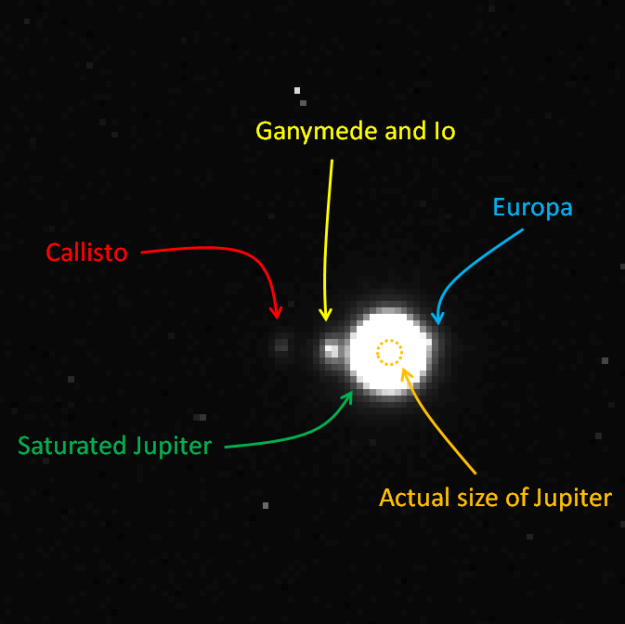

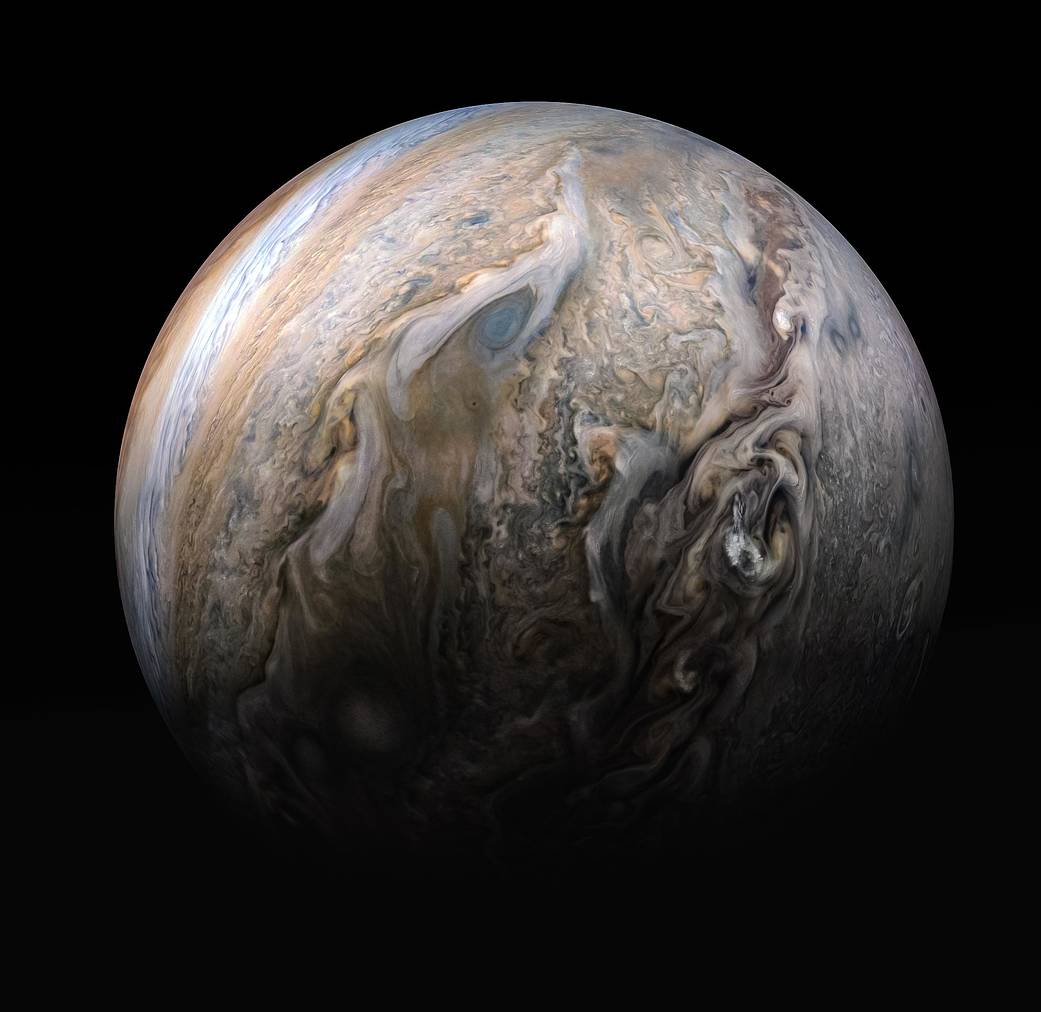

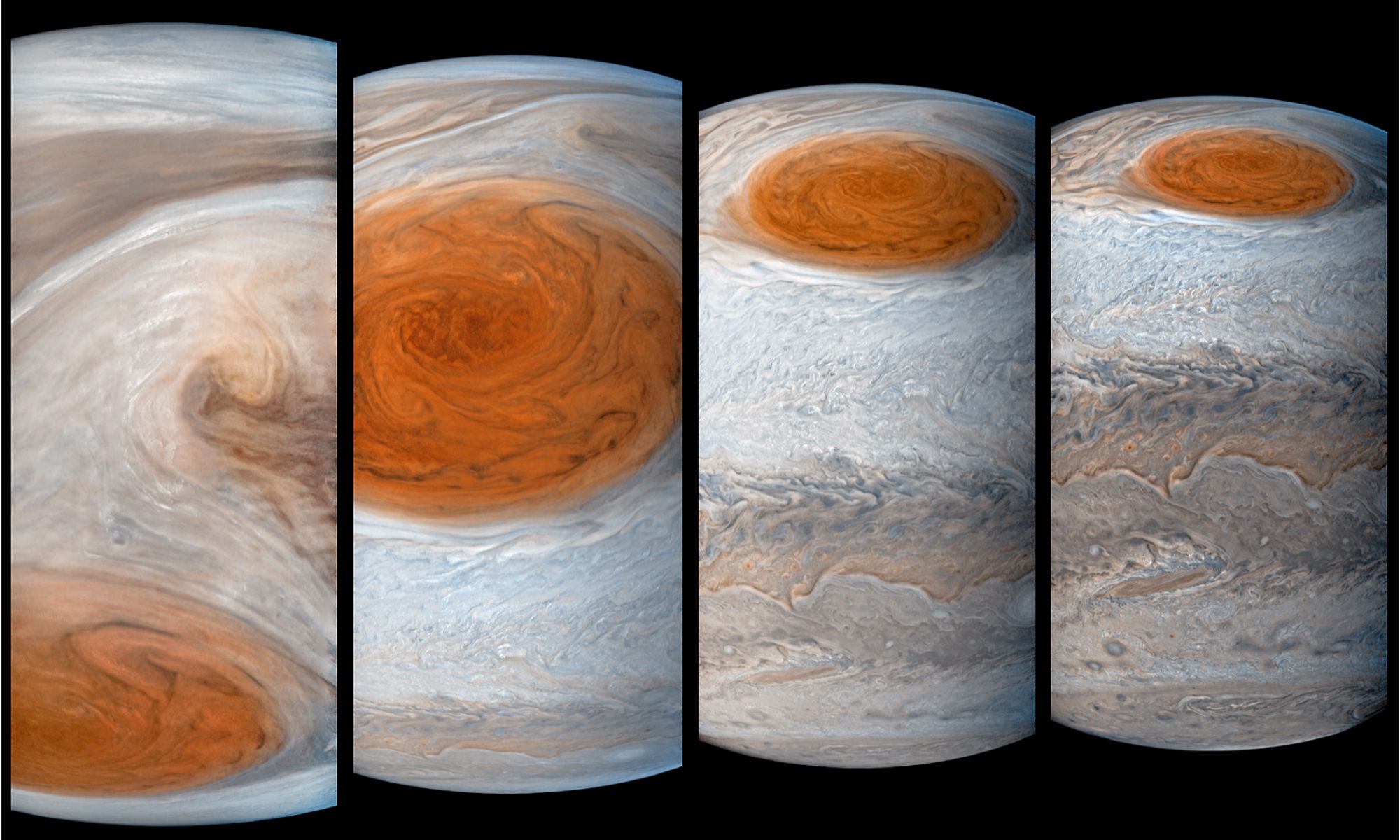

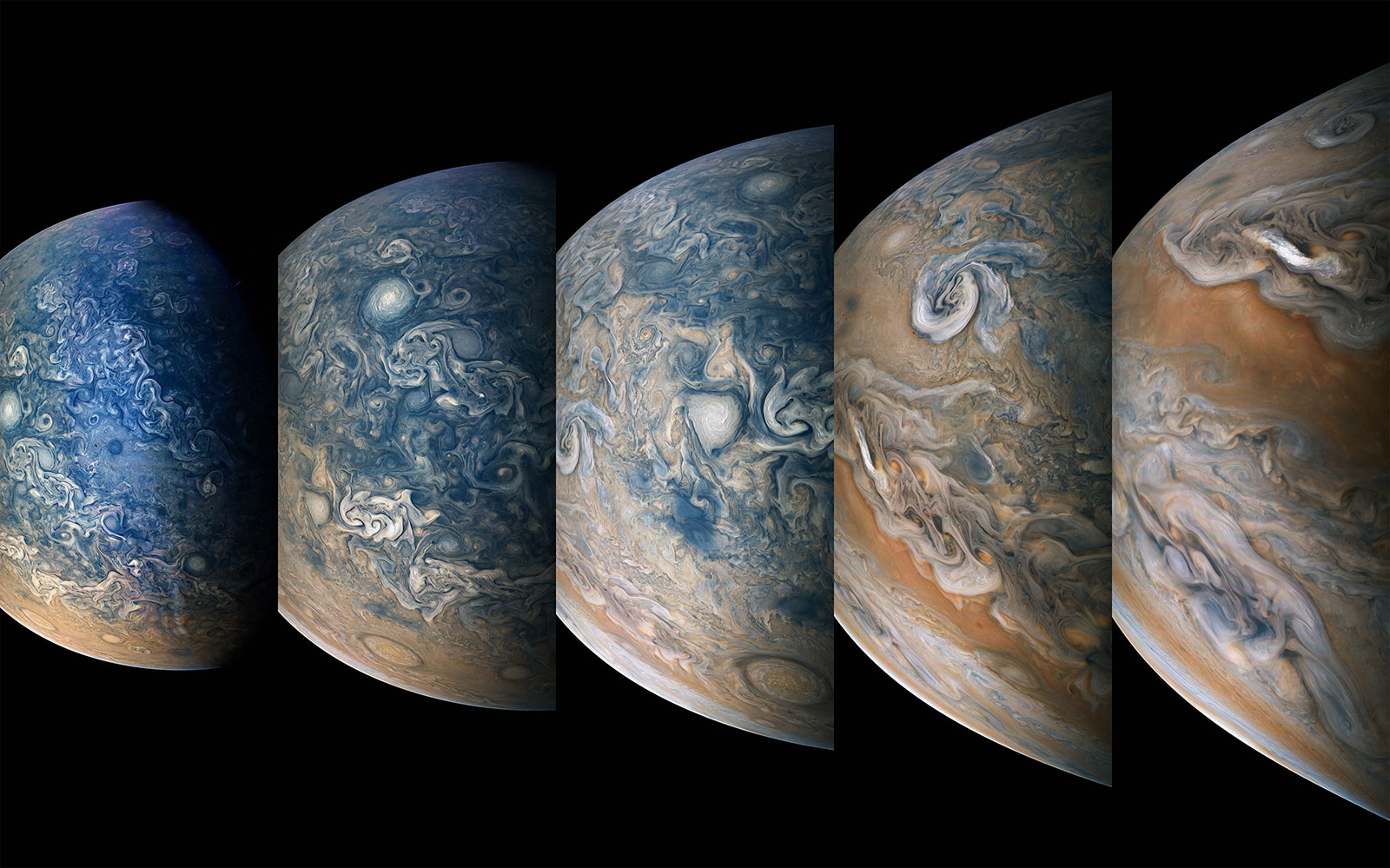

Thanks to a mission extension, NASA’s Juno probe continues to orbit Jupiter, being only the second spacecraft in history to do so. Since it arrived around the gas giant on July 5th, 2016, Juno has managed to gather a great deal of information on Jupiter’s atmosphere, magnetic and gravity environment, and its interior structure.

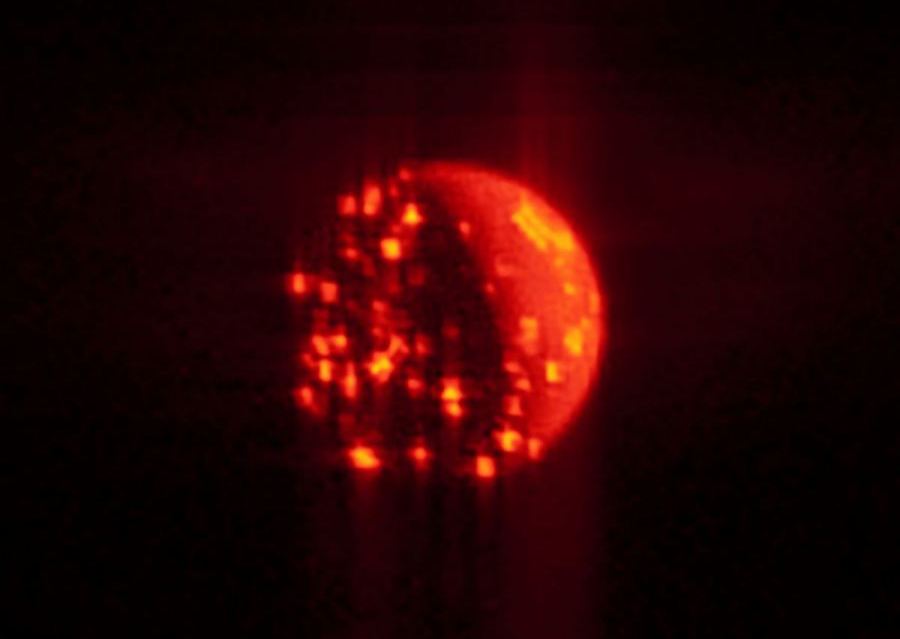

In that time, the probe has also managed to capture some breathtaking images of Jupiter as well. But on December 21st, during the probe’s sixteenth orbit of the gas giant, the Juno probe changed things up when four of its cameras captured images of the Jovian moon Io, showcasing its polar regions and spotting what appeared to be a volcanic eruption.

Continue reading “Juno Saw One of Io’s Volcanoes Erupting During its Recent Flyby”