Simple choices can sometimes lead to dramatic turns of events in our lives. Before turning in for the night last night, I opened the front door for one last look at the night sky. A brighter-than-normal auroral arc arched over the northern horizon. Although no geomagnetic activity had been forecast, there was something about that arc that hinted of possibility.

It was 11:30 at the time, and it would have been easy to go to bed, but I figured one quick drive north for a better look couldn’t hurt. Ten minutes later the sky exploded. The arc subdivided into individual pillars of light that stretched by degrees until they reached the zenith and beyond. Rhythmic ripples of light – much like the regular beat of waves on a beach — pulsed upward through the display. You can’t see a chill going up your spine, but if you could, this is what it would look like.

Auroras can be caused by huge eruptions of subatomic particles from the Sun’s corona called CMEs or coronal mass ejections, but they can also be sparked by holes in the solar magnetic canopy. Coronal holes show up as blank regions in photos of the Sun taken in far ultraviolet and X-ray light. Bright magnetic loops restrain the constant leakage of electrons and protons from the Sun called the solar wind. But holes allow these particles to fly away into space at high speed. Last night’s aurora traces its origin back to one of these holes.

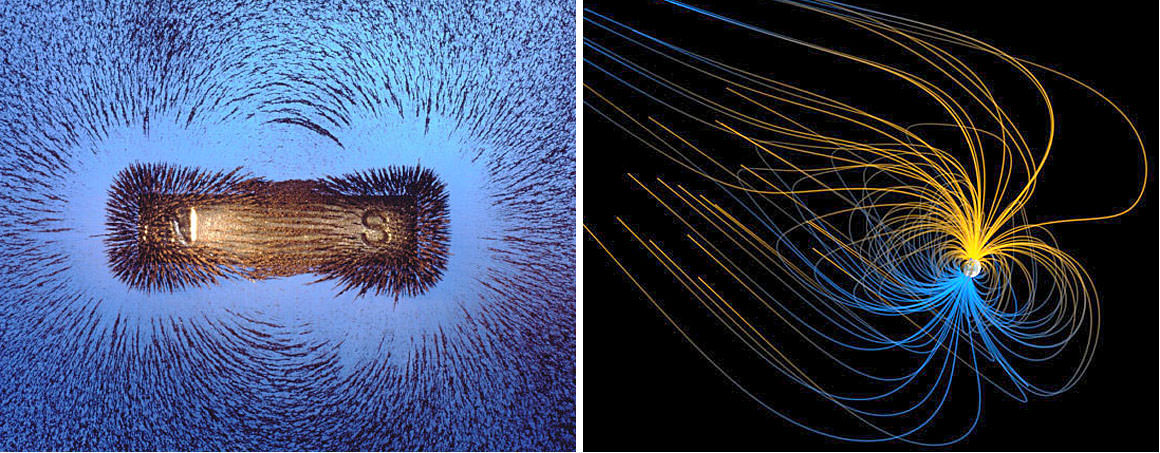

The subatomic particles in the gusty wind come bundled with their own magnetic field with a plus or positive pole and a minus or negative pole. Recall that an ordinary bar magnet also has a “+” and “-” pole, and that like poles repel and opposite poles attract. Earth likewise has magnetic poles which anchor a large bubble of magnetism around the planet called the magnetosphere.

Field lines in the magnetosphere — those invisible lines of magnetic force around every magnet — point toward the north pole. When the field lines in the solar wind also point north, there’s little interaction between the two, almost like two magnets repelling one another. But if the cloud’s lines of magnetic force point south, they can link directly into Earth’s magnetic field like two magnets snapping together. Particles, primarily electrons, stream willy-nilly at high speed down Earth’s magnetic field lines like a zillion firefighters zipping down fire poles. They crash directly into molecules and atoms of oxygen and nitrogen around 60-100 miles overhead, which absorb the energy and then release it moments later in bursts of green and red light.

So do great forces act on the tiniest of things to produce a vibrant display of northern lights. Last night’s show began at nightfall and lasted into dawn. Good news! The latest forecast calls for another round of aurora tonight from about 7 p.m. to 1 a.m. CDT (0-6 hours UT). Only minor G1 storming (K index =5) is expected, but that was last night’s expectation, too. Like the weather, the aurora can be tricky to pin down. Instead of a G1, we got a G3 or strong storm. No one’s complaining.

So if you’re looking for that perfect last minute Mother’s Day gift, take your mom to a place with a good view of the northern sky and start looking at the end of dusk for activity. Displays often begin with a low, “quiet” arc and amp up from there.

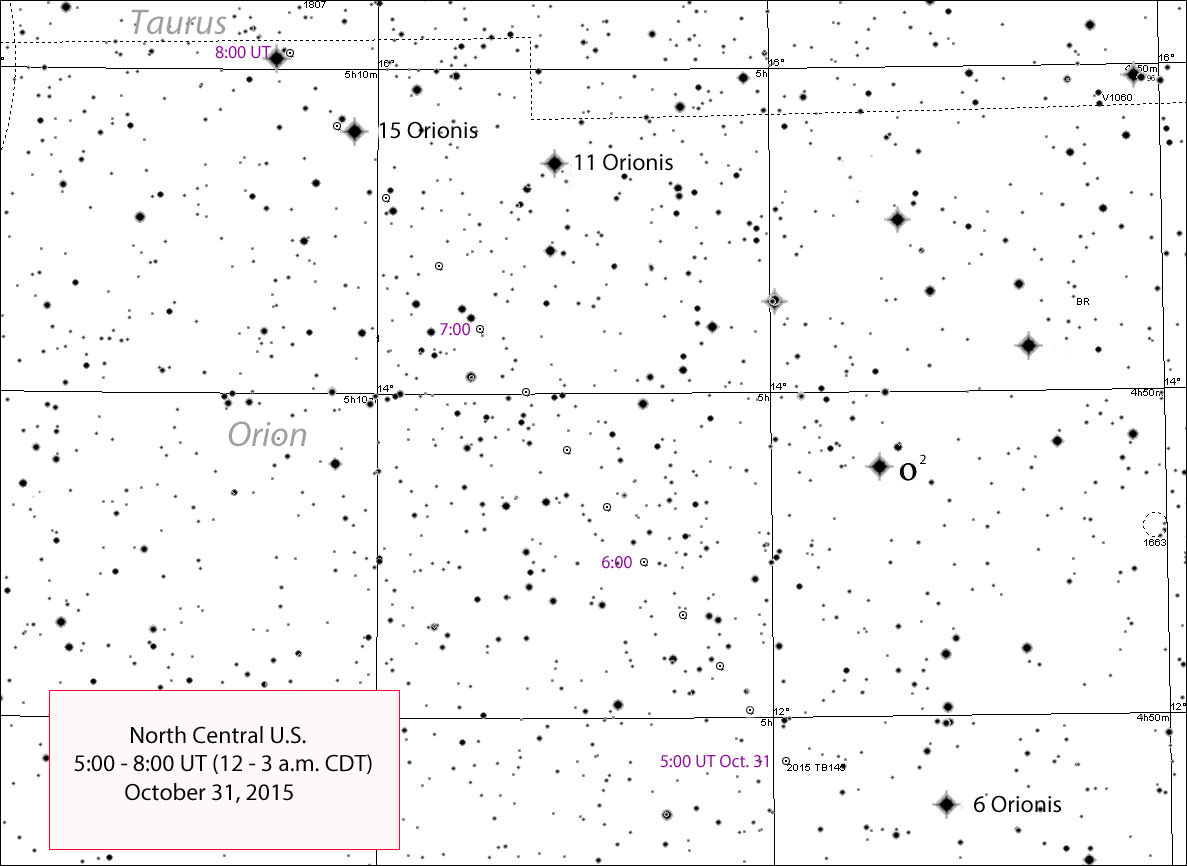

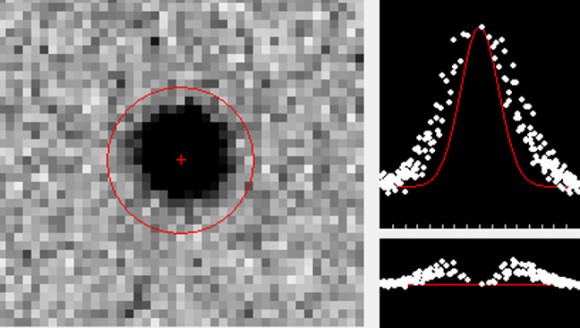

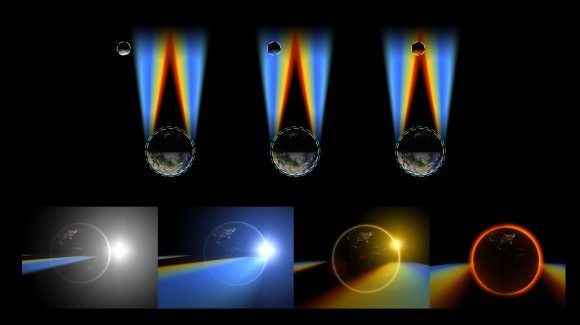

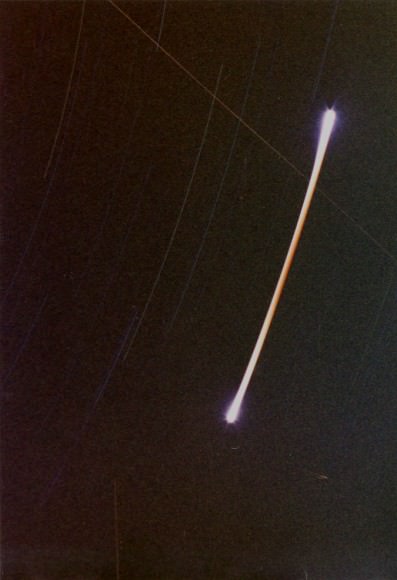

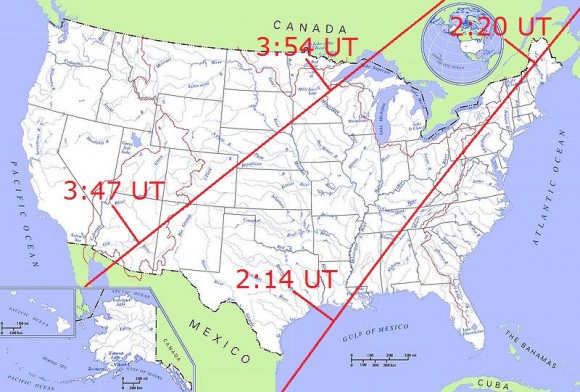

Aurora or not, tomorrow features a big event many of us have anticipated for years — the transit of Mercury. You’ll find everything you’ll need to know in this earlier story, but to recap, Mercury will cross directly in front of the Sun during the late morning-early evening for European observers and from around sunrise (or before) through late morning-early afternoon for skywatchers in the Americas. Because the planet is tiny and the Sun deadly bright, you’ll need a small telescope capped with a safe solar filter to watch the event. Remember, never look directly at the Sun at any time.

If you’re greeted with cloudy skies or live where the transit can’t be seen, be sure to check out astronomer Gianluca Masi’s live stream of the event. He’ll hook you up starting at 11:00 UT (6 a.m. CDT) tomorrow.

The table below includes the times across the major time zones in the continental U.S. for Monday May 9:

| Time Zone | Eastern (EDT) | Central (CDT) | Mountain (MDT) | Pacific (PDT) |

| Transit start | 7:12 a.m. | 6:12 a.m. | 5:12 a.m. | Not visible |

| Mid-transit | 10:57 a.m. | 9:57 a.m. | 8:57 a.m. | 7:57 a.m. |

| Transit end | 2:42 p.m. | 1:42 p.m. | 12:42 p.m. | 11:42 a.m. |