[/caption]

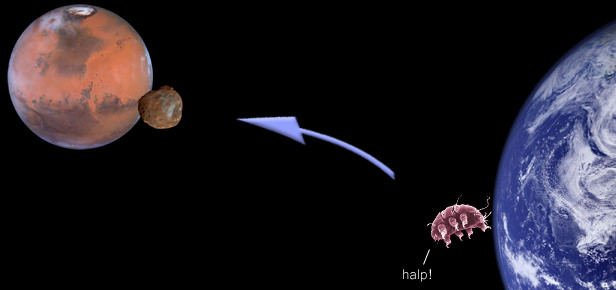

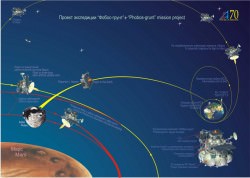

How ironic. Not content with searching for life on Mars, the Russian space agency and the US-based Planetary Society will soon be sending terrestrial life to the Martian moon Phobos. The mini-interplanetary travellers will consist of bacteria, spores, seeds, crustaceans, insects and fungi. Why? To see how biological life, in various forms, deals with space travel spanning three years.

So if you thought that a human (or monkey) would be the first of Earth’s ambassadors to land on Mars or one of its moons, you’d be very mistaken…

The mosquito was a part of the Biorisk project, and the scientists knew the insect had the ability to drop into a “suspended animation” during times of draught in Africa. The African mosquito can turn its bodily water into tricallosa sugar, slowing its functions nearly to a stop. When the rain returns, the crystallised creature is rehydrated and it can carry on its lifecycle. The Biorisk mosquito however survived 18 months with no sustenance, exposed to temperatures ranging from -150°C to +60°C. When returned to Earth, Russian scientists gave the hardy mozzie a health check, declaring:

“We brought him back to Earth. He is alive, and his feet are moving.” — Anatoly Grigoryev, Vice President of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

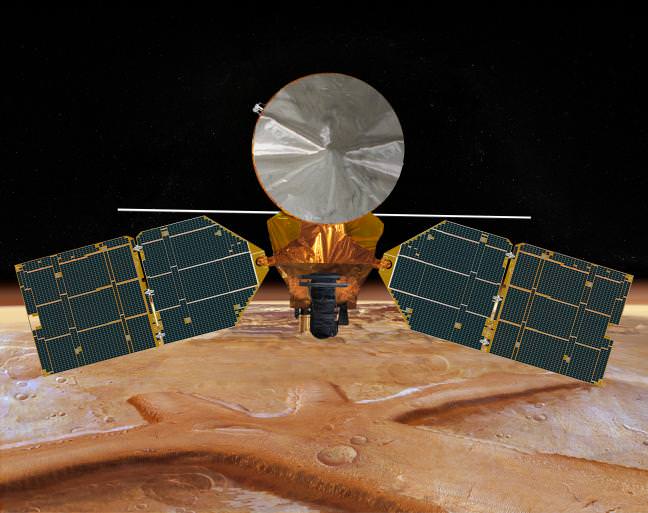

So that’s the idea behind sending creatures into space: we need to understand how animals and plants deal with space travel. This will aid the understanding of how humans will cope in space for long periods, plus we need to understand if there are any harmful effects from growing foodstuffs away from our planet. This is why the Russian space agency wants to go one step further when it launches its Phobos-Grunt mission next year, to send biological specimens on a voyage of a lifetime. A return trip to the Martian moon Phobos.

Russia on the other hand has far loftier goals; the space agency will attach a small petting zoo. Inside the Russian experiment will include crustaceans, mosquito larvae (already proven to be enthusiastic space travellers), bacteria and fungi. The Russian experiment will specifically look at how cosmic radiation can effect these different types of life during an interplanetary trip (essential ahead of any manned attempt to the Red Planet).

Naturally, there are some concerns about contamination to the moon (if Phobos-Grunt doesn’t do the “return” part of the mission), but the chances of any extraterrestrial life being harboured on this tiny piece of airless rock are low. Having said that, we just don’t know, so the mission scientists will have to be very careful to ensure containment. Besides, there’s something unsettling about infecting an alien world with our bacteria before we’ve even had the chance to get there ourselves…

Source: Discovery