Data from Mars orbiters and landers have suggested that any past water on the Red Planet’s surface probably came from subsurface moisture bubbling up from underground. But a new study of Martian soil data implies that Mars’ atmosphere was once thick enough to hold moisture and that dew or even drizzle hit the ground. Geoscientists at the University of California Berkeley combined data from the Viking 1 and 2 landers, the Pathfinder rover, and the current rovers Spirit and Opportunity. The scientists say tell-tale signs of this type of moisture are evident on the planet’s surface.

“By analyzing the chemistry of the planet’s soil, we can derive important information about Mars’ climate history,” said Ronald Amundson, UC Berkeley professor of ecosystem sciences and the study’s lead author. “The dominant view, put forward by many now working on the Mars missions, is that the chemistry of Mars soils is a mix of dust and rock that has accumulated over the eons, combined with impacts of upwelling groundwater, which is almost the exact opposite of any common process that forms soil on Earth. In this paper, we try to steer the discussion back by re-evaluating the Mars data using geological and hydrological principles that exist on Earth.”

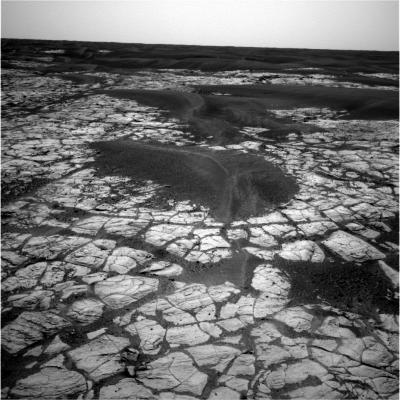

The team says soil at the various spacecraft landing sites have lost significant fractions of the elements that make up the rock fragments from which the soil was formed. This is a sign, they say, that water once moved downward through the dirt, carrying the elements with it. Amundson also pointed out that the soil also shows evidence of a long period of drying, as evidenced by surface patterns of the now sulfate-rich land. The distinctive accumulations of sulfate deposits are characteristic of soil in northern Chile’s Atacama Desert, where rainfall averages approximately 1 millimeter per year, making it the driest region on Earth.

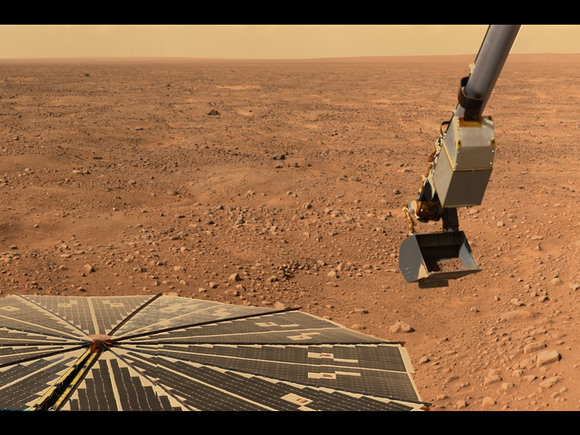

Researchers compared images such as this image of the Atacama Desert with the above image taken by the Opportunity rover on Mars, which show similar surface patterns.

“The Atacama Desert and the dry valleys of Antarctica are where Earth meets Mars,” said Amundson. “I would argue that Mars has more in common geochemically with these climate extremes on Earth than these sites have in common with the rest of our planet.”

Amundson noted that sulfate is prevalent in Earth’s oceans and atmosphere, and is incorporated in rainwater. However, it’s so soluble that it typically washes away from the surface of the ground when it rains. The key for the distinctive accumulation in soil to appear is for there to be enough moisture to move it downward, but not so much that it is washed away entirely.

The researchers also noted that the distribution of the chemical elements in Martian soil, where sulfates accumulate on the surface with layers of chloride salt underneath, suggest atmospheric moisture.

“Sulfates tend to be less soluble in water than chlorides, so if water is moving up through evaporation, we would expect to find chlorides at the surface and sulfates below that,” said Amundson. “But when water is moving downward, there’s a complete reversal of that where the chlorides move downward and sulfates stay closer to the surface. There have been weak but long-term atmospheric cycles that not only add dust and salt but periodic liquid water to the soil surface that move the salts downward.”

Amundson pointed out that there is still debate among scientists about the degree to which atmospheric and geological conditions on Earth can be used as analogs for the environment on Mars. He said the new study suggests that Martian soil may be a “museum” that records chemical information about the history of water on the planet, and that our own planet holds the key to interpreting the record.

“It seems very logical that a dry, arid planet like Mars with the same bedrock geology as many places on Earth would have some of the same hydrological and geological processes operating that occur in our deserts here on Earth,” said Amundson. “Our study suggests that Mars isn’t a planet where things have behaved radically different from Earth, and that we should look to regions like the Atacama Desert for further insight into Martian climate history.”

Original News Source: EurekAlert