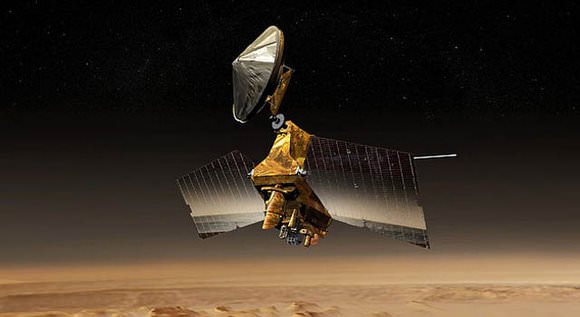

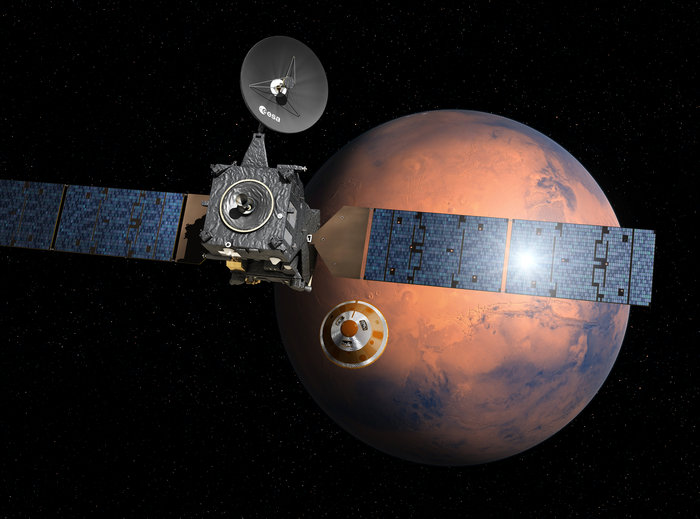

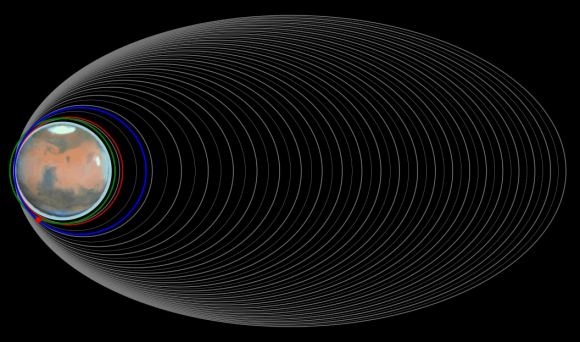

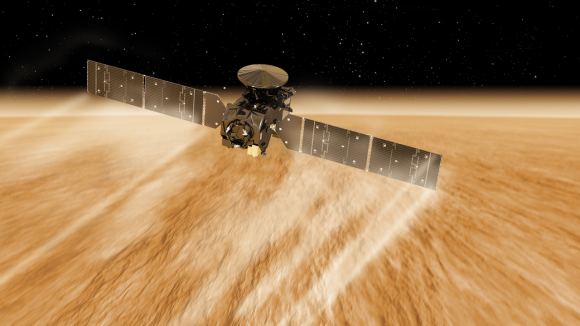

The ESA’s Mars Express probe has been studying Mars and its Moons for many years. While there are several missions currently in orbit around Mars, Mars Express‘s near-polar elliptical orbit gives it some advantages over the others. For one, its orbital path takes it closer to Phobos than any other spacecraft, which allows it to periodically observe the moon from distances of around 150 km (93 mi).

Because of this, the probe is in an ideal position to study Mars’ moons and capture images of them. On occasion, this allows for some interesting photo opportunities. For example, in November of 2017, while taking pictures of Phobos and Deimos, the probe spotted Saturn in the background. This fortuitous event led to the creation of some beautiful images, which were put together to produce a video.

Since 2003, Mars Express has been studying Phobos and Deimos in the hopes of learning more about these mysterious objects. While it has learned much about their size, appearance and position, much remains unknown about their composition, how and where they formed, and what their surface conditions are like. To answer these questions, the probe has been conducting regular flybys of these moons and taking pictures of them.

The video that was recently released by the ESA combines 30 such images which show Phobos passing through the frame. In the background, Saturn is visible as a small ringed dot, despite being roughly 1 billion km away. The images that were used to create this video were taken by the probes High Resolution Stereo Camera on November 26th, 2016, while the probe was traveling at a speed of about 3 km/s.

This photobomb was not unexpected, since the Mars Express repeatedly uses background reference stars and other bodies in the Solar System to confirm positions of the moons in the sky. In so doing, the probe is able to calculate the position of Phobos and Deimos with an accuracy of up to a few kilometers. The probes ideal position for capturing detailed images has also helped scientists to learn more about the surface features and structure of the two moons.

For instance, the pictures taken during the probe’s close flybys of Phobos showed its bumpy, irregular and dimpled surface in detail.The moon’s largest impact crater – the Stickney Crater – is also visible in one of the frames. Measuring 9 km ( mi) in diameter, this crater accounts for a third of the moon’s diameter, making it one the largest impact craters relative to body size in the Solar System.

In another image, taken on January 15th, 2018, Deimos is visible as an irregular and partially shadowed body in the foreground, while the delicate rings of Saturn are just visible encircling the small dot in the background (see below). In addition, Mars Express also obtained images of Phobos set against a reference star on January 8th, 2018 (see above) and close-up images of Phobos’ pockmarked surface on September 12th, 2017.

In the future, the Mars Express probe is expected to reveal a great deal more about Mars’ system of moons. In addition to the enduring questions of their origins, formation and composition, there are also questions about where future missions could land in order to study the surface directly. In particular, Phobos has been considered for a possible landing and sample-return mission.

Because of its nearness to Mars and the fact that one side is always facing towards the planet, the moon could make for an ideal location for a permanent observation post. This post would allow for the long-term study of the Martian surface and atmosphere, could act as a communications relay for other spacecraft, and could even serve as a base for future missions to the surface.

If and when such a mission to Phobos becomes a reality, it is the Mars Express probe that will determine where the ideal landing site would be. In essence, by studying the Martian moons to learning more about them, Mars Express is helping to prepare future missions to the Red Planet.

Be sure to check out the time-lapse video of Phobos and Saturn, courtesy of the ESA:

Further Reading: ESA

![The Viking 2 lander captured this image of itself on the Martian surface. The Viking Landers were the last missions to directly look for life on Mars. By NASA - NASA website; description,[1] high resolution image.[2], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17624](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/608px-Viking2lander1-580x458.jpg)