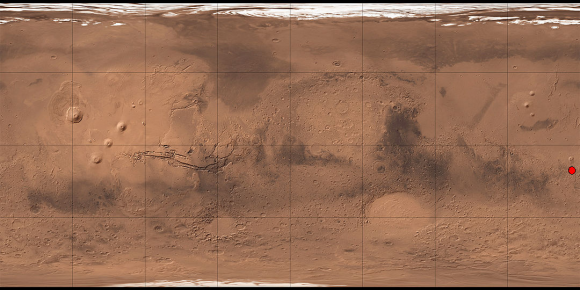

The planet Mars has few things in common. Both planets have roughly the same amount of land surface area, sustained polar caps, and both have a similar tilt in their rotational axes, affording each of them strong seasonal variability. Additionally, both planets present strong evidence of having undergone climate change in the past. In Mars’ case, this evidence points towards it once having a viable atmosphere and liquid water on its surface.

At the same time, our two planets are really quite different, and in a number of very important ways. One of these is the fact that gravity on Mars is just a fraction of what it is here on Earth. Understanding the effect this will likely have on human beings is of extreme importance when it comes time to send crewed missions to Mars, not to mention potential colonists.

Mars Compared to Earth:

The differences between Mars and Earth are all crucial for the existence of life as we know it. For instance, atmospheric pressure on Mars is a tiny fraction of what it is here on Earth – averaging 7.5 millibars on Mars to just over 1000 here on Earth. The average surface temperature is also lower on Mars, ranking in at a frigid -63 °C compared to Earth’s balmy 14 °C.

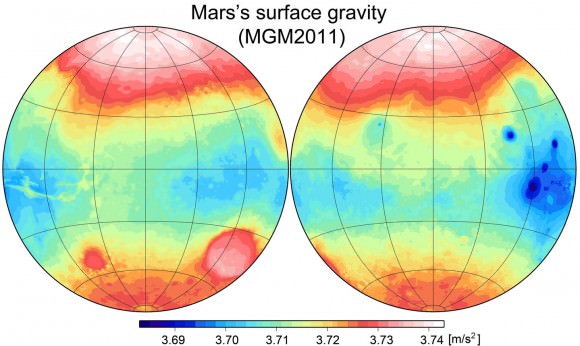

And while the length of a Martian day is roughly the same as it is here on Earth (24 hours 37 minutes), the length of a Martian year is significantly longer (687 days). On top that, the gravity on Mars’ surface is much lower than it is here on Earth – 62% lower to be precise. At just 0.376 of the Earth standard (or 0.376 g), a person who weighs 100 kg on Earth would weigh only 38 kg on Mars.

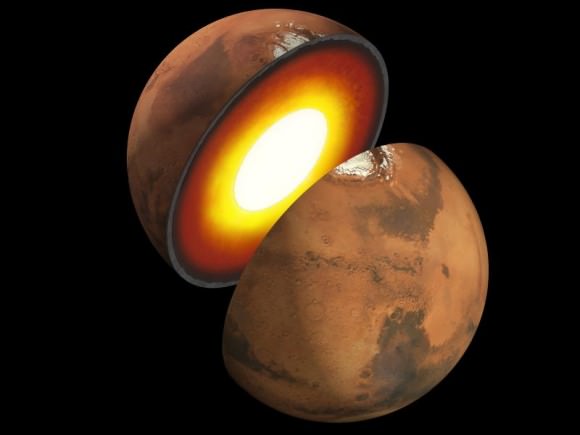

This difference in surface gravity is due to a number of factors – mass, density, and radius being the foremost. Even though Mars has almost the same land surface area as Earth, it has only half the diameter and less density than Earth – possessing roughly 15% of Earth’s volume and 11% of its mass.

Calculating Martian Gravity:

Scientists have calculated Mars’ gravity based on Newton’s Theory of Universal Gravitation, which states that the gravitational force exerted by an object is proportional to its mass. When applied to a spherical body like a planet with a given mass, the surface gravity will be approximately inversely proportional to the square of its radius. When applied to a spherical body with a given average density, it will be approximately proportional to its radius.

These proportionalities can be expressed by the formula g = m/r2, where g is the surface gravity of Mars (expressed as a multiple of the Earth’s, which is 9.8 m/s²), m is its mass – expressed as a multiple of the Earth’s mass (5.976·1024 kg) – and r its radius, expressed as a multiple of the Earth’s (mean) radius (6,371 km).

For instance, Mars has a mass of 6.4171 x 1023 kg, which is 0.107 times the mass of Earth. It also has a mean radius of 3,389.5 km, which works out to 0.532 Earth radii. The surface gravity of Mars can therefore be expressed mathematically as: 0.107/0.532², from which we get the value of 0.376. Based on the Earth’s own surface gravity, this works out to an acceleration of 3.711 meters per second squared.

Implications:

At present, it is unknown what effects long-term exposure to this amount of gravity will have on the human body. However, ongoing research into the effects of microgravity on astronauts has shown that it has a detrimental effect on health – which includes loss of muscle mass, bone density, organ function, and even eyesight.

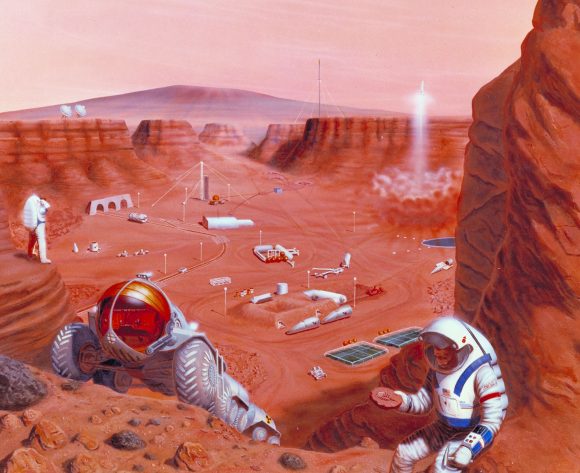

Understanding Mars’ gravity and its affect on terrestrial beings is an important first step if we want to send astronauts, explorers, and even settlers there someday. Basically, the effects of long-term exposure to gravity that is just over one-third the Earth normal will be a key aspect of any plans for upcoming manned missions or colonization efforts.

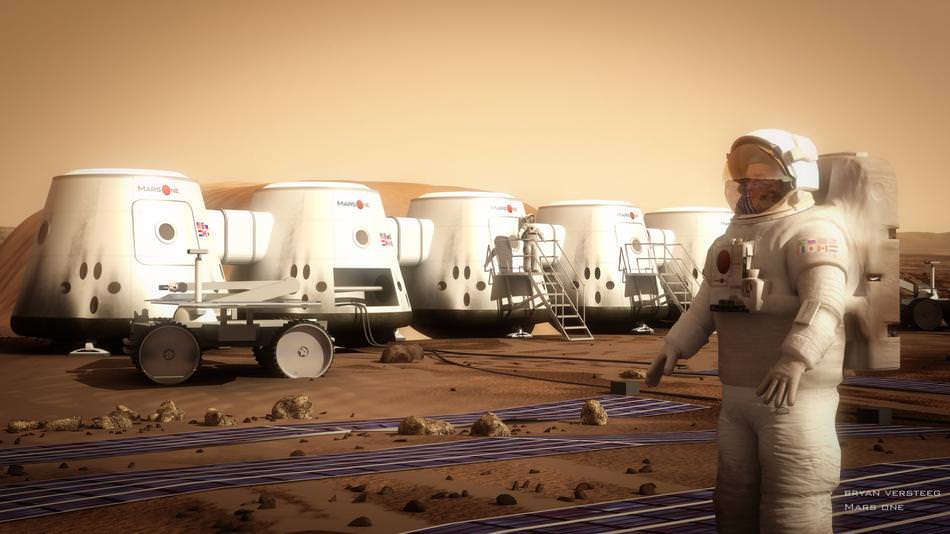

For example, crowd-sourced projects like Mars One make allowances for the likelihood of muscle deterioration and osteoporosis for their participants. Citing a recent study of International Space Station (ISS) astronauts, they acknowledge that mission durations ranging from 4-6 months show a maximum loss of 30% muscle performance and maximum loss of 15% muscle mass.

Their proposed mission calls for many months in space to get to Mars, and for those volunteering to spend the rest of their lives living on the Martian surface. Naturally, they also claim that their astronauts will be “well prepared with a scientifically valid countermeasures program that will keep them healthy, not only for the mission to Mars, but also as they become adjusted to life under gravity on the Mars surface.” What these measures are remains to be seen.

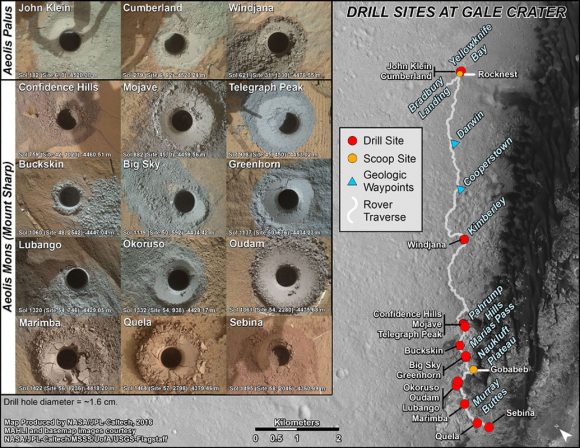

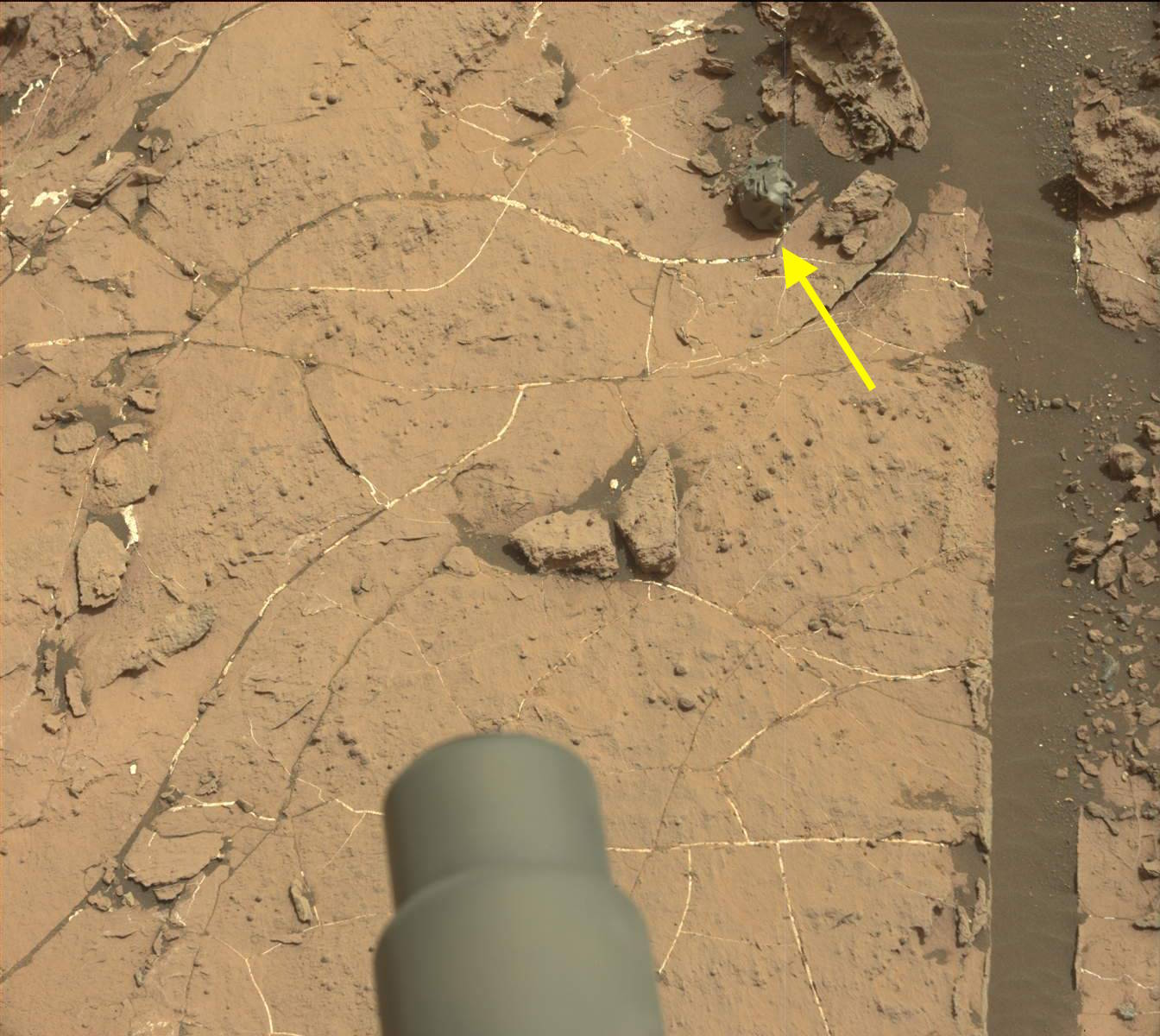

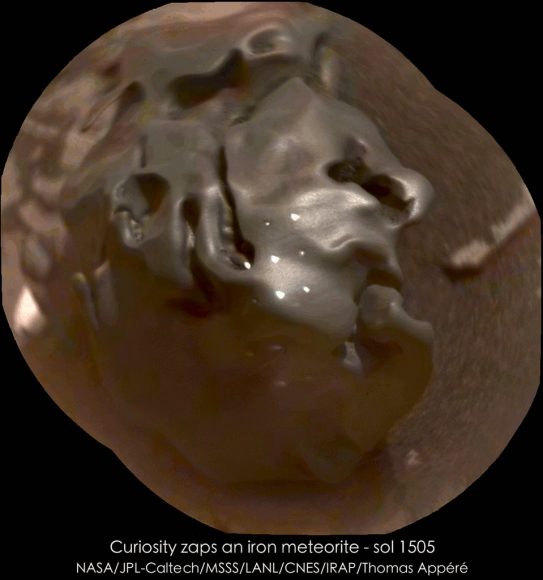

Learning more about Martian gravity and how terrestrial organisms fare under it could be a boon for space exploration and missions to other planets as well. And as more information is produced by the many robotic lander and orbiter missions on Mars, as well as planned manned missions, we can expect to get a clearer picture of what Martian gravity is like up close.

As we get closer to NASA’s proposed manned mission to Mars, which is currently scheduled to take place in 2030, we can certainly expect that more research efforts will be attempted.

We have written many interesting articles about Mars here at Universe Today. Here’s How Strong is the Gravity on Other Planets?, Martian Gravity to be Tested on Mice, Mars Compared to Earth, Asteroids Can Get Shaken and Stirred by Mars’ Gravity, How Do We Colonize Mars? How Can We Live on Mars?, and How Do We Terraform Mars?

Information on the Mars Gravity Biosatellite. And the kids might like this; a project they can build to demonstrate Mars gravity.

Astronomy Cast also has some wonderful episodes on the subject. Here’s Episode 52: Mars, and Episode 95: Humans to Mars, Part 2 – Colonists.

Sources: