The Kansas Cosmosphere and Space Center. (Elizabeth Howell)

Hutchinson, KS — While the nation is polarized between choosing Barack Obama or Mitt Romney as the next American president, voters going to the polls in this city of 40,000 will have another matter to weigh during elections today.

Along with their ballot, residents will consider whether the Kansas Cosmosphere and Space Center will continue to receive funding from city coffers. Since it represents 18% of revenues for the science museum, Cosmosphere president Jim Remar says his colleagues have been paying close attention.

The city sales tax sets aside 33% of a quarter-cent for the Cosmosphere, and some additional funding for a nearby underground salt museum and other city initiatives. Money to the museum goes for general operations.

“I feel good that it’s going to pass, although we do have some nervous moments,” Remar says. Supporters of the tax have been spreading the word through radio, billboards, editorials in local newspapers and any other means possible to get out the word.

Museum president Jim Remar, inside the Cosmosphere’s restoration facility. (Elizabeth Howell)

Sales tax funding for the Cosmosphere renews every five years, with the current iteration set to expire in 2014. The city tries to get the vote out for the sales tax at the same time as the general election, for convenience and financial sake.

While 18% of the museum’s funding lie in the hands of voters, Remar is trying to increase the share of the remaining 82% under the Cosmosphere’s control.

Getting visitors out to the museum is always a challenge; it’s an hour from the nearest major center (Wichita), a city that itself is many hours’ drive from any city to speak of. Still, the museum brings in 120,000 people every year, an attendance figure that includes space camps, museum visits and other events.

For the city itself, though, the museum is a jewel: “I can’t think of any other town of 40,000 that has such a facility,” says Remar, speaking proudly of how he grew up in the area, left and then chose to come back to help lead the museum’s management. His focus now is on trying to bring in business connections to enhance the Cosmosphere’s power in the community.

One of the most promising aspects is the Cosmosphere’s restoration and fabrication facility. The museum is perhaps most famous for putting the pieces of the Apollo 13 Odyssey spacecraft back together around the same time the movie came out in 1995. This was no easy task, as Odyssey was disassembled and scattered during an investigation into a near-fatal explosion aboard the spacecraft in 1970.

The restored control panel in Apollo 13’s Odyssey spacecraft, which sits in the Cosmosphere. (Elizabeth Howell)

The Cosmosphere required the Smithsonian’s help as the museum hunted through NASA centers, contract facilities and other spots for months in search of missing pieces. More than 85% of the spacecraft, which is on display at the Cosmosphere, was retrieved. The rest of the components came from spares and other odd pieces the Cosmosphere could find.

Restoration capabilities came out of necessity, Remar says. In the mid-1980s, the museum had a need to put spacecraft on display and spiffy them up for visitors. As other museums had the same requirement, the Cosmosphere gradually built out capabilities in restoration.

“It’s not something where somebody can come in a day and do it. It is a lot of trial and error,” Remar says of the employees who work in the facility. The lead mechanic has been around for 14 years, though, and there are two other workers with him who have adapted well over the years.

Cosmosphere officials realized there are only so many spacecraft to restore, and added exhibitions, replication and fabrication to their capabilities. This positioned them well for a surge of Hollywood films and other productions in the 1990s, such as Apollo 13, HBO’s From the Earth to the Moon, a short-lived TV series in the ’90s called The Cape and (in the 2000s) the IMAX film Magnificent Desolation: Walking on the Moon 3D.

An individual project will cost anywhere from $10,000 to $2.5 million to build; overall revenues from this division are 15 to 20% of the museum’s coffers every year. And that could grow bigger very soon.

A tool box inside the Cosmosphere’s restoration facility. (Elizabeth Howell)

On Saturday, a “Science of Aliens” exhibit will open in Taipei at the National Taiwan Science Education Center. One major part is a UFO spacecraft – 19 feet wide by 7 feet tall – that the Cosmosphere built for the exhibit. It includes running lights and some alien-sounding noises.

Asia happens to be a hot economy these days compared with North America and Europe, where the Comosphere’s work historically went.

The Cosmosphere is in discussions with Taipei-based Universal Impression, a broker that negotiated the science museum work, to do more work in the future. Remar says he hopes the Cosmosphere’s presence there will serve as a calling card to other Asian clients.

“International work can explode here,” he says. “There’s a lot of potential.”

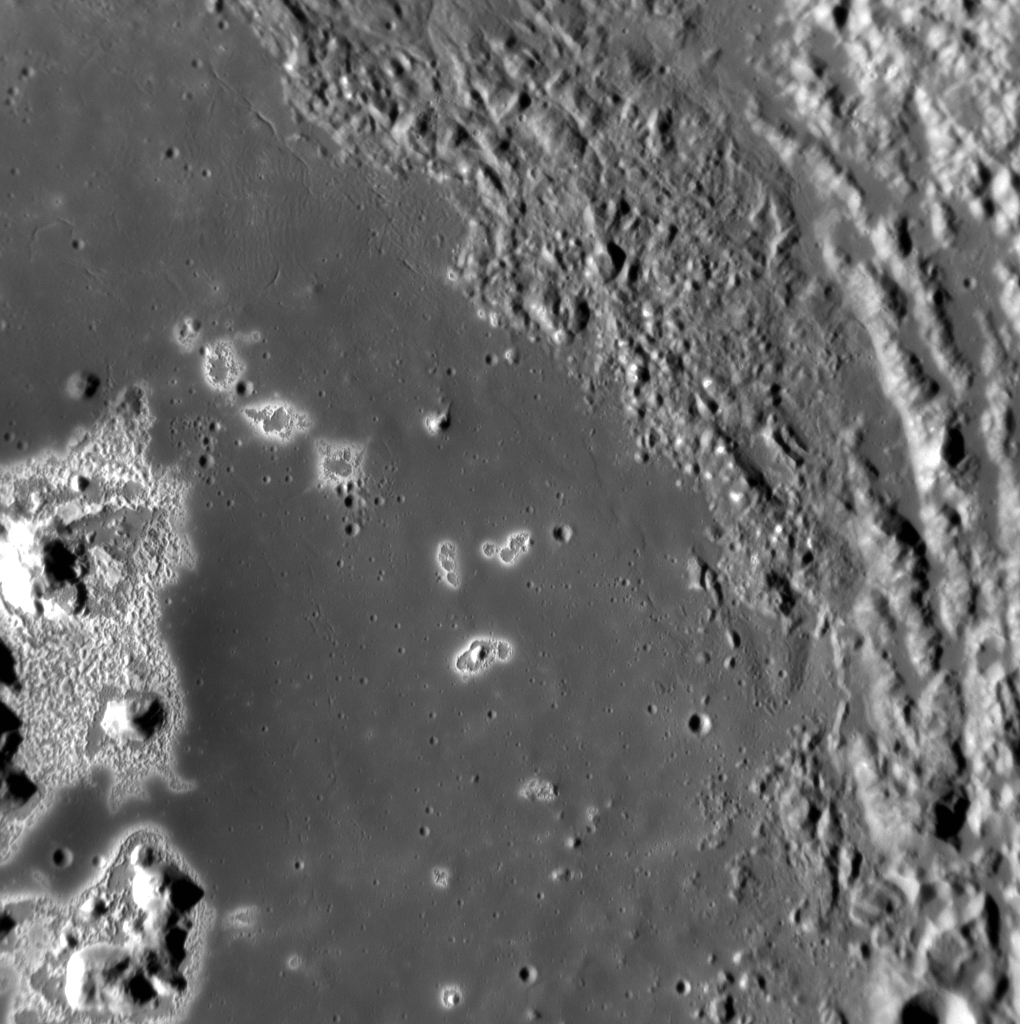

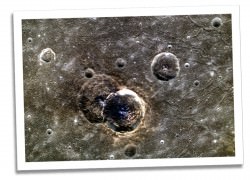

And even though the ratio of calcium silicates is higher than what’s found on Mercury today, Irving speculates that the fragments of NWA 7325 could have come from a deeper part of Mercury’s crust, excavated by a powerful impact event and launched into space, eventually finding their way to Earth.

And even though the ratio of calcium silicates is higher than what’s found on Mercury today, Irving speculates that the fragments of NWA 7325 could have come from a deeper part of Mercury’s crust, excavated by a powerful impact event and launched into space, eventually finding their way to Earth.