Greetings, fellow SkyWatchers! Let’s begin the week with some awesome galactic studies and enjoy a meteor shower during Summer Solstice! We’ll be studying variable stars, the planet Mars, Saturn, the Moon and Mercury, too! There’s always a bit of astronomy history and some unusual things to learn about. When you’re ready, just meet me in the back yard…

Monday, June 18 – With dark skies on our side, we’ll spend the next few days concentrating on a very specific region of the night sky. Legend tells us the constellation of Crater is the cup of the gods – cup befitting the god of the skies, Apollo. Who holds this cup, dressed in black? It’s the Raven, Corvus. The tale is a sad one – a story of a creature sent to fetch water for his master, only to tarry too long waiting on a fig to ripen. When he realized his mistake, the sorry Raven returned to Apollo with his cup and brought along the serpent Hydra in his claws as well. Angry, Apollo tossed them into the sky for all eternity and it is in the south they stay until this day.

For the next few days, it will be our pleasure to study the Cup and the Raven. The galaxies I have chosen are done particularly for those of us who still star hop. I will start with a “marker” star that should be easily visible unaided on a night capable of supporting this kind of study. The field stars are quite recognizable in the finder and this is an area that takes some work. Because these galaxies approach magnitude 13, they are best suited to the larger telescope.

Now, let’s go between map and sky and identify both Zeta and Eta Crater and form a triangle. Our mark is directly south of Eta the same distance as between the two stars. At low power, the 12.7 magnitude NGC 3981 (Right Ascension: 11 : 56.1 – Declination: -19 : 54) sits inside a stretched triangle of stars. Upon magnification, an elongated, near edge-on spiral structure with a bright nucleus appears. Patience and aversion makes this “stand up” galaxy appear to have a vague fading at the frontiers with faint extensions. A moment of clarity is all it takes to see tiny star caught at the edge.

Tuesday, June 19 – New Moon! Tonight’s first study object, 12.7 magnitude NGC 3956 (Right Ascension: 11 : 54.0 – Declination: -20 : 34) is about a degree due south of NGC 3981. When first viewed, it appears as edge-on structure at low power. Upon study it takes on the form of a highly inclined spiral. A beautiful multiple star, and a difficult double star also resides with the NGC 3956 – appearing almost to triangulate with it. Aversion brings up a very bright core region which over the course of time and study appears to extend away from the center, giving this very sweet galaxy more structure than can be called from it with one observation.

Our next target is a little more than two degrees further south of our last study. The 12.8 magnitude NGC 3955 (Right Ascension: 11 : 54.0 – Declination: -23 : 10) is a very even, elongated spiral structure requiring a minimum of aversion once the mind and eye “see” its position. Not particularly an impressive galaxy, the NGC 3955 does, however, have a star caught at the edge as well. After several viewings, the best structure I can pull from this one is a slight concentration toward the core.

Now we’ll study an interacting pair and all that is required is that you find 31 Corvii, an unaided eye star west of Gamma and Epsilon Corvii. Now we’re ready to nudge the scope about one degree north. The 11th magnitude NGC 4038/39 (Right Ascension: 12 : 01.9 – Declination: -18 : 52) is a tight, but superior pair of interacting galaxies. Often referred to as either the “Ringtail” or the “Antenna”, this pair deeply captured the public’s imagination when photographed by the Hubble. (Unfortunately, we don’t have the Hubble, but what we have is set of optics and the patience to find them.) At low power the pair presents two very stellar core regions surrounded by a curiously shaped nebulosity. Now, drop the power on it and practice patience – because it’s worth it! When that perfect moment of clarity arrives, we have crackling structure. Unusual, clumpy, odd arms appear at strong aversion. Behind all this is a galactic “sheen” that hints at all the beauty seen in the Hubble photographs. It’s a tight little fellow, but worth every moment it takes to find it.

Return to 31 Corvii and head one half degree northwest to discover 11.6 magnitude NGC 4027 (Right Ascension: 11 : 59.5 – Declination: -19 : 16). Relatively large, and faint at low power, this one also deserves both magnification and attention. Why? Because it rocks! It has a wonderful coma shape with a single, unmistakable bold arm. The bright nucleus seems to almost curl along with this arm shape and during aversion a single stellar point appears at its tip. This one is a real treat!

Wednesday, June 20 – Today marks the official date of 2012 Summer Solstice!

With no Moon to contend with in the predawn hours, we welcome the “shooting stars” as we pass through another portion of the Ophiuchid meteor stream. The radiant for this pass will be nearer Sagittarius and the fall rate varies from 8 to 20, but it can sometimes produce unexpectedly more.

Tonight let’s look to the sky again and fixate on Eta Crater – our study lay one half degree southeast. The 12.8 magnitude NGC 4033 (Right Ascension: 12 : 00.6 – Declination: -17 : 51) is a tough call even for a large scope. Appearing elliptical at low power, it does take on some stretch at magnification. It is smallish, even and quite unremarkable. It requires good aversion and a bit of patience to find. Good luck!

The last of our studies resides by a star, one degree west of Beta Corvii. In order to “see” anything even remotely called structure in NGC 4462 (Right Ascension: 12 : 29.3 – Declination: -23 : 10), this one is a high power only galaxy that is best when the accompanying star is kept out of the field as much as possible. It holds a definite stellar nucleus and a concentration that pulls away from it making it almost appear barred. On an exceptional night with a large scope, wide aversion and moments of clarity show what may be three to four glints inside the structure. Ultra tiny pinholes in another universe? Or perhaps an unimaginably huge, bright globular clusters? While attention is focused on trying to draw out these points, you’ll notice this galaxy’s structure much more clearly. Another true beauty and fitting way to end this particular study field!

Thursday, June 21 – Keep an eye out for the exiting planet Mars! It’s been on the move and has now crossed the border of Virgo and returned to Leo. Have you noticed it quickly changing in both apparent brightness and size? It won’t be long until it’s gone! And speaking of planets on the move, have you spotted Mercury yet? You can find the swift little planet low on the western horizon just after sunset. Look for it just to the south of Castor and Pollux!

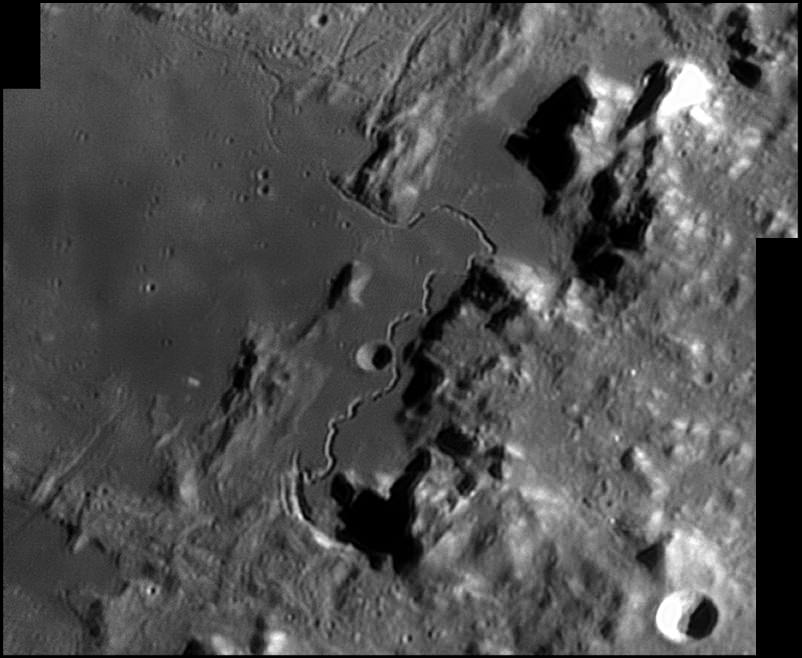

For challenging larger telescope studies, return to eastern edge of Mare Crisium and Promontorium Agarum to identify shallow crater Condorcet to its east. Look along the shore of the mare for a mountain to the south known as Mons Usov. Just to its north Luna 24 landed and directly to its west are the remains of Luna 15. We’ll study more about them in the future. Can you spot the tiny dark well of crater Fahrenheit nearby? Continue with your telescope north of Mare Crisium for even more challenging features such as northeast limb studies Mare Smythii and Mare Marginis. Between them you will see the long oval crater Jansky – bordered by Jansky A at the very outer edge.

While you’re out tonight, take a look at the skies for a circlet of seven stars that reside about halfway between orange Arcturus and brilliant blue/white Vega. This quiet constellation is named Corona Borealis – or the “Northern Crown.” Just northwest of its brightest star is a huge concentration of over 400 galaxies that reside over a billion light-years away from us. This area is so small from our point of view that we could cover it with our thumbnail held at arm’s length!

For variable star fans, let’s explore Corona Borealis and focus our attention on S – located just west of Theta – the westernmost star in the constellation’s arc formation. At magnitude 5.3, this long-term variable takes almost a year to go through its changes; usually far outshining the 7th magnitude star to its northeast – but will drop to a barely visible magnitude 14 at minimum. Compare it to the eclipsing binary U Coronae Borealis about a degree northwest. In slightly over three days this Algol-type will range by a full magnitude as its companions draw together.

Friday, June 22 – Today celebrates the founding of the Royal Greenwich Observatory in 1675. That’s 332 years of astronomy! Also on this date in history, in 1978, James Christy of the US Naval Observatory in Flagstaff Arizona discovered Pluto’s satellite Charon.

If you’d like to practice some unaided eye astronomy, then look no further than the western skyline as the Sun sets. At twilight you’ll first notice the very slender crescent Moon – but don’t delay your observations as you can spot Mercury to the west! The inner planet will set very fast, so you’ll need an open horizon. But that’s not all… the speedy little dude is lined up perfectly with Castor and Pollux! With the foursome nearly “in a row” this will make a very cool apparition to remind friends and family to watch for!

Now, grab your favorite optics for a selenographic treat tonight return to the area just north of Mare Crisium area to observe spectacular crater Cleomides. This two million year old crater is separated from Crisium by some 60 kilometers of mountainous terrain. Telescopically, Cleomides is a true delight at high power. To Cleomides’ east, begin by identifying Delmotte, and to the northwest, Trailes and Debes. About twice Clemoides’ width northwest, you will see a sharply well-defined Class I crater Geminus. Named for the Greek astronomer and mathematician Geminos, this 86 kilometer wide crater shows a smooth floor and displays a long, low dune across its middle.

When you’re finished, point your binoculars or telescopes back towards Corona Borealis and about three fingerwidths northwest of Alpha for variable star R (Ra 15. 48.6 Dec +28 09). This star is a total enigma. Discovered in 1795, most of the time R carries a magnitude near 6, but can drop to magnitude 14 in a matter of weeks – only to unexpectedly brighten again! It is believed that R emits a carbon cloud which blocks its light. When studied at minima, the light curve resembles a “reverse nova,” and has a peculiar spectrum. It is very possible this ancient Population II star has used all of its hydrogen fuel and is now fusing helium to carbon. It’s so odd that science can’t even directly determine its distance!

Saturday, June 23 – If you missed yesterday’s apparition of Mercury, then try again tonight. While the small planet might be dim, just look for the brighter pairing of Castor and Pollux above the western horizon at twilight. Can’t find it? Then try this. When you look at this famous pair of stars, judge the distance between the two. Now, apply that same distance and angle to the left (southern) star, Pollux, and you’ve found Mercury! Need more? Then check out the Moon and you’ll see Regulus is about a fistwidth to the east/southeast and Mars is a little more than two handspans to the southeast. Still more? Then continue on from Mars southeast about about another two handspans and you’ll see the pairing of Spica and Saturn!

Using your telescope tonight on the Moon will call up previous study craters, Atlas and Hercules to the lunar north. If you walk along the terminator to the due west of Atlas and Hercules, you’ll see the punctuation of 40 kilometer wide Burg just emerging from the shadows. While it doesn’t appear to be a grand crater just yet, it has a redeeming feature – it’s deep – real deep. If Burg were filled with water here on Earth, it would require a deep submergence vehicle like ALVIN to reach its 3680 meter floor! This class II crater stands nearly alone on an expanse of lunarscape known as Lacus Mortis. If the terminator has advanced enough at your time of viewing, you may be able to see this walled-plain’s western boundary peeking out of the shadows.

While we’re out, let’s have a look at Delta Serpens. To the eye and binoculars, 4th magnitude Delta is a widely separated visual double star… But power up in the telescope to have a look at a wonderfully difficult binary. Divided by no more than 4 arc seconds, 210 light-year distant Delta and its 5th magnitude companion could be as old as 800 million years and on the verge of becoming evolved giants. Separated by about 9 times the distance of Pluto from our Sun, the white primary is a Delta Scuti-type variable which changes subtly in less than four hours. Although it takes the pair 3200 years to orbit each other, you’ll find Delta Serpens to be an excellent challenge for your optics.

Sunday, June 24 – On this day in 1881, Sir William Huggins made the first photographic spectrum of a comet (1881 III) and discovered cyanogen (CN) emission at violet wavelengths. Unfortunately, his discovery caused public panic around 29 years later when Earth passed through the tail of Halley’s Comet. What a shame the public didn’t realize that cyanogens are also released organically! More than fearing what is in a comet’s tail, they should have been thinking about what might happen should a comet strike. Tonight look at the wasted Southern Highland area of the Moon with new eyes… Many of these craters you see were caused by impacts – some as large as the nucleus of Halley itself.

Now let’s pick up a binocular curiosity located on the northeast shore of Mare Serenitatis. Re-identify the bright ring of Posidonius, which contains several equally bright points both around and within it – and look at Mare Crisium and get a feel for its size. A little more than one Crisium’s length west of Posidonius you’ll meet Aristotle and Eudoxus. Drop a similar length south and you will be at the tiny, bright crater Linne on the expanse of Mare Serenitatis. So what’s so cool about this little white dot? With only binoculars you are resolving a crater that is one mile wide, in a seven mile wide patch of bright ejecta – from close to 400,000 kilometers away! While you were there, did you notice how much Proclus has changed tonight? It is now a bright circle and beginning to show bright lunar rays…

Before we head for deep sky, be sure to at least take a look at Saturn and Mars. Right now the Ring King has reached its greatest westward position and will begin its tour back to the east. Now, check out Mars’ position to the west and measure with your hands roughly how far apart they are. At this point they are separated by about two handspans. Check again in a few weeks to see planetary motion displayed right before your eyes!

Now let’s turn binoculars or telescopes towards magnitude 2.7 Alpha Librae – the second brightest star in the celestial “Scales.” Its proper name is Zuben El Genubi, and even as “Star Wars” as that sounds, the “Southern Claw” is actually quite close to home at a distance of only 65 light-years. No matter what size optics you are using, you’ll easily see Alpha’s 5th magnitude companion widely spaced and sharing the same proper motion. Alpha itself is a spectroscopic binary which was verified during an occultation event, and its inseparable companion is only a half magnitude dimmer according to the light curves. Enjoy this easy pair tonight!

Until next week? Ask for the Moon… But keep on reaching for the stars!