[/caption]

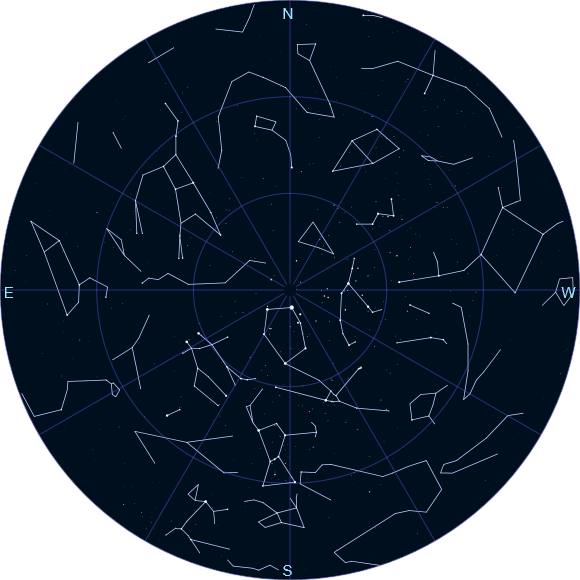

Greetings, fellow SkyWatchers! It’s going to be a great week for lunar studies and an even better time to study some interesting single stars. Need more? Then keep an eye on the skies as the Delta Leonid meteor shower heats up towards its later week peak. Get out those binoculars and telescopes and I’ll see you in the backyard…

Monday, February 27 – With tonight’s Moon in a much higher position to observe, let’s begin with an investigation of Mare Fecunditatis – the Sea of Fertility. Stretching 1463 kilometers in diameter, the combined area of this mare is equal in size to the Great Sandy Desert in Australia – and almost as vacant in interior features. It is home to glasses, pyroxenes, feldspars, oxides, olivines, troilite and metals in its lunar soil, which is called regolith. Studies show the basaltic flow inside of the Fecunditatis basin perhaps occurred all at once, making its chemical composition different from other maria. The lower titanium content means it is between 3.1 and 3.6 billion years old!

The western edge of Fecunditatis is home to features we share terrestrially – grabens. These down-dropped areas of landscape between parallel fault lines occur where the crust is stretched to the breaking point. On Earth, these happen along tectonic plates, but on the Moon they are found around basins. The forces created by lava flow increase the weight inside the basin, causing a tension along the border which eventually fault and cause these areas. Look closely along the western shore of Fecunditatis where you will see many such features.

Today is the birthday of Bernard Lyot. Born in 1897, Lyot went on to become the inventor of the coronagraph in 1930. By all accounts, Lyot was a wonderful and generous man who sadly died of a heart attack when returning from a trip to view a total eclipse. Although we cannot hand you a corona, we can show you a star that wears its own gaseous envelope.

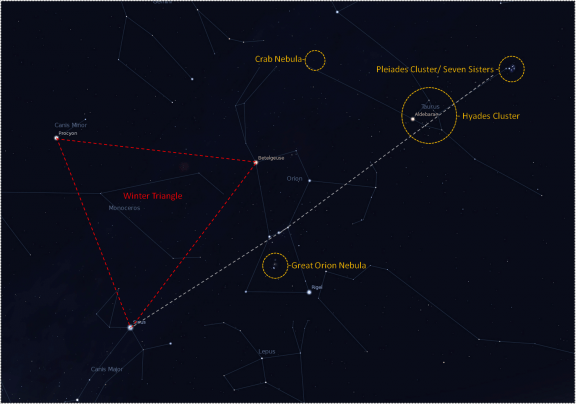

Let’s go to our maps west of M36 and M38 to identify AE Aurigae. As an unusual variable, AE is normally around 6th magnitude and resides approximately 1600 light years distant. The beauty in this region is not particularly the star itself but the faint nebula in which it resides known as IC 405, an area of mostly dust and very little gas. What makes this view so entertaining is that we are looking at a “runaway” star. It is believed that AE once originated from the M42 region in Orion. Cruising along at a very respectable speed of 80 miles per second, AE flew the “stellar nest” some 2.7 million years ago! Although IC 405 is not directly related to AE, there is evidence within the nebula that areas have been cleared of their dust by the rapid northward motion of the star. AE’s hot, blue illumination and high energy photons fuel what little gas is contained within the region. Its light also reflects off the surrounding dust. Although we cannot “see” with our eyes like a photograph, together the pair forms an outstanding view for the small backyard telescope and it is known as “The Flaming Star.”

Tuesday, February 28 – Since the stars of our study constellation of Monoceros are quite dim when the Moon begins to interfere, why not spend a few days really taking a look at the Moon’s surface and familiarizing yourself with its many features? Tonight would be a great time for us to explore “The Sea of Nectar.” At around 1000 meters deep, Mare Nectaris covers an area of the Moon equal to that of the Great Sandhills in Saskatchewan, Canada. Like all maria, it is part of a gigantic basin that is filled with lava, and evidence of grabens exists along its western basin edge. While Nectaris’ basaltic flows appear darker than those in most maria, it is one of the older formations on the Moon and as the terminator progress, you’ll be able to see where ejecta belonging to Tycho crosses its surface. For now? Let’s have a closer look at the mare itself and its surrounding craters… Enjoy these many features which are also lunar challenges – and we’ll be back to study each later in the year!

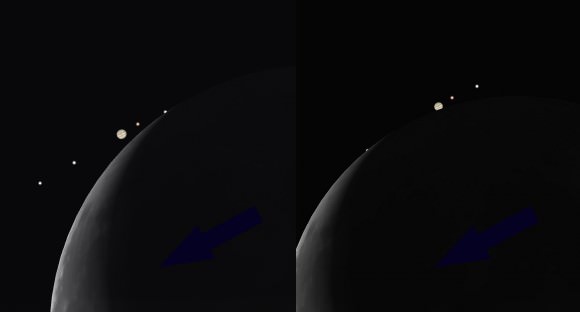

Now, let’s have a look about a fistwidth north-northwest of Sirius – for Beta Monocerotis. Discovered by Sir William Herschel in 1781, Beta is perhaps one of the most outstanding triple systems in the sky, with each of its three bright, white components near equal magnitude. Residing about 100-200 light-years away, these identical spectral type stars are separated by no more than 400 AU and don’t appear to have changed positions since measured by Struve in 1831. Although you won’t be able to split this system with binoculars, even a small telescope will pick apart their brilliancy and make Beta a star to remember!

Wednesday, February 29 – Tonight let your imagination sweep you away as we go mountain climbing – on the Moon! Tonight all of Mare Serenitatis will be revealed and along its northwestern shore lie some of the most beautiful mountain ranges you’ll ever view – The Caucasus to the north and the Apennines to the south. Like its earthly counterpart, the Caucasus Mountain range stretches almost 550 kilometers and some of its peaks reach upwards to 6 kilometers – a summit as high as Mount Elbrus!

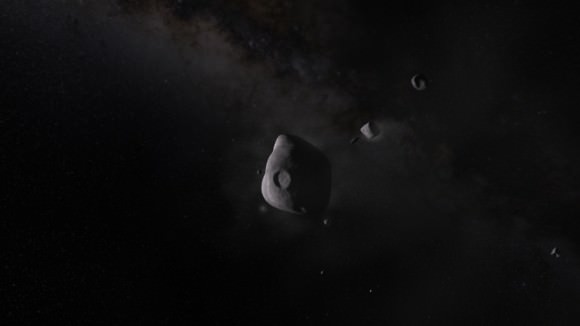

Slightly smaller than its terrestrial namesake, the lunar Apennine mountain range extends some 600 kilometers with peaks rising as high as 5 kilometers. Be sure to look for Mons Hadley, one of the tallest peaks that you will see at the northern end of this chain. It rises above the surface to a height of 4.6 kilometers, making that single mountain about the size of asteroid Toutatis.

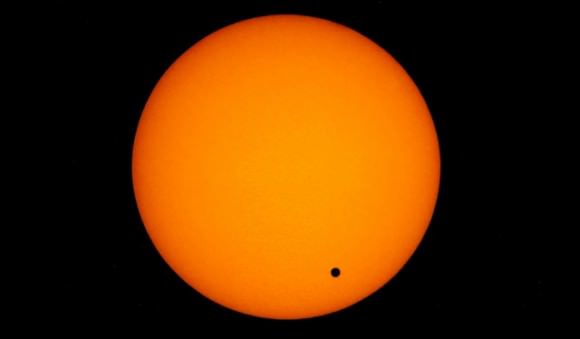

Thursday, March 1 – In 1966 Venera 3 became the first craft to touch another world as it impacted Venus. Although its communications failed before it could transmit data, it was a milestone achievement.

George Abell was born on this day in 1927. Abell was the man responsible for cataloging 2712 clusters of galaxies from the Palomar sky survey, which was completed in 1958. Using these plates, Abell put forth the idea that the grouping of such clusters distinguished the arrangement of matter in the universe. He developed the “luminosity function,” which shows relationship between brightness and number of members in each cluster, allowing you to infer their distances. Abell also discovered a number of planetary nebulae and developed the theory (along with Peter Goldreich) of their evolution from red giants. Abell was a fascinating lecturer and a developer of many television series dedicated to explaining science and astronomy in a fun and easy to understand format. He was also a president and member of the Board of Directors for the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, as well as serving in the American Astronomical Society, the Cosmology Commission of the International Astronomical Union, and he accepted editorship of the Astronomical Journal just before he died.

Tonight your lunar assignments are relatively easy. We will begin by identifying “The Sea of Vapors.” Look for Mare Vaporum on the southwest shore of Mare Serenitatis. Formed from newer lava flow inside an old crater, this lunar sea is edged to its north by the mighty Apennine Mountains. On its northeastern edge, look for the now washed-out Haemus Mountains. Can you see where lava flow has reached them? This lava has come from different time periods and the slightly different colorations are easy to spot even with binoculars.

Further south and edged by the terminator is Sinus Medii – “The Bay in the Middle.” With an area about the size of both Massachusetts and Connecticut, this lunar feature is the mid-point of the visible lunar surface. In 1930, experiments were underway to test this region for surface temperature – a project begun by Lord Rosse in 1868. Surprisingly enough, results of the two studies were very close, and during full daylight temperatures in Sinus Medii can reach the boiling point as evidenced by Surveyors 4 and 6 – which landed near its center.

Now take a hop north of Mare Vaporum for a look at “The Rotten Swamp” – Palus Putredinus. More pleasingly known as the “Marsh of Decay,” this nearly level surface of lava flow is also home to a mission – the hard-landing of Lunik 2. On September 13, 1959 astronomers in Europe reported seeing the black dot of the crashing probe. The event lasted for nearly 300 seconds and spread over an area of 40 kilometers

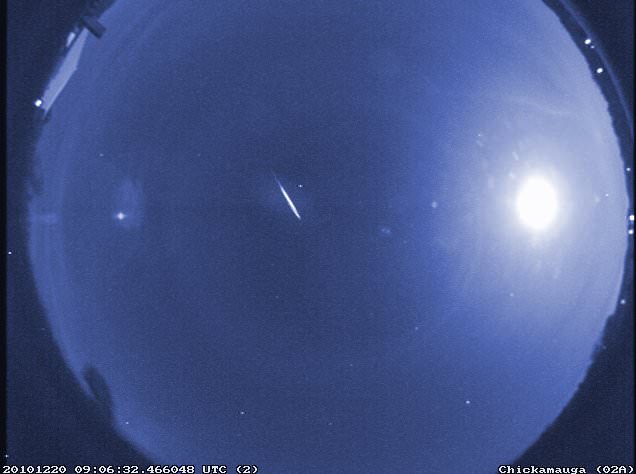

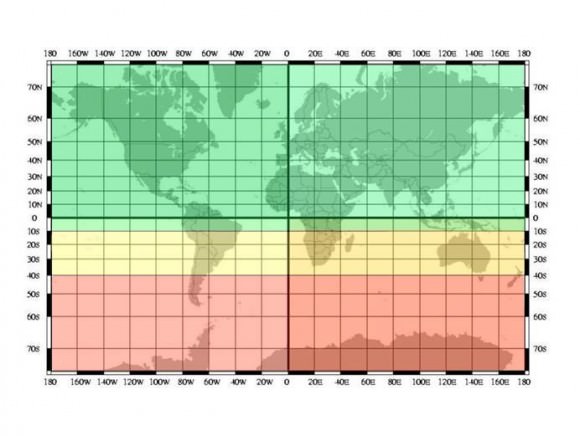

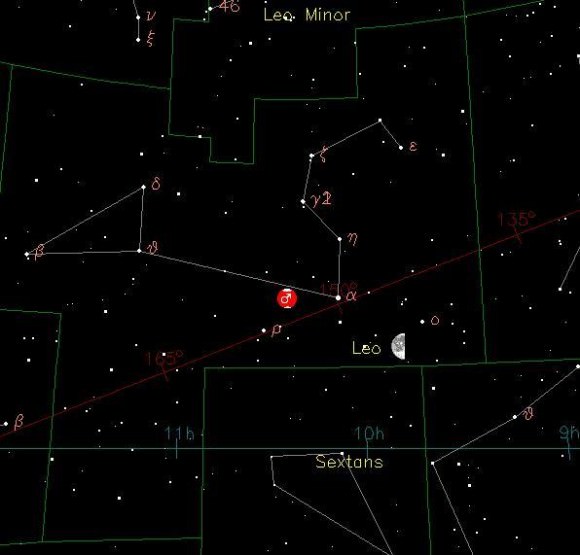

Friday, March 2 – Tonight it’s time to relax and enjoy the Delta Leonid meteor shower. Burning through our atmosphere at speeds of up to 24 kilometers per second, these slow travelers will seem to radiate from a point around the middle of Leo’s “back.” The fall rate is rather slow at around 5 per hour, but they are still worth keeping a watch for!

Tonight let’s return again to the lunar surface to study how the terminator has moved and take a close look at the way features change as the Sun brightens the moonscape. Can you still see Langrenus? How about Theophilus, Cyrillus and Catharina? Does Posidonius still look the same? Each night features further east become brighter and harder to distinguish – yet they also change in subtle and unexpected ways. We’ll look at that in the days ahead, but tonight let’s walk the terminator as one of the most beautiful features has now come into view – “The Bay of Rainbows.” Sinus Iridum’s C-shape is easily recognizable in even small binoculars – yet there are a wonderland of small details in and around the area for the small telescope that we’ll study as the year goes by.

Saturday, March 3 – Tonight’s bright skies are brought to you by the Moon! Have you noticed how difficult it is to see any stars belonging to Monoceros with these conditions? Don’t worry. We’ll be back. For now, let’s continue onwards with our lunar studies as we locate the emerging “Sea Of Islands.” Mare Insularum will be partially revealed tonight as one of the most prominent of lunar craters – Copernicus – now comes into view. While only a small section of this reasonably young mare is now visible southeast of Copernicus, the lighting will be just right to spot its many different colored lava flows. To the northeast is a lunar club challenge: Sinus Aestuum. Latin for the Bay of Billows, this mare-like region has an approximate diameter of 290 kilometers, and its total area is about the size of the state of New Hampshire. Containing almost no features, this area is low albedo – providing very little surface reflectivity.

Tonight let’s try a lovely triple star system – Beta Monocerotis. Located about a fist width northwest of Sirius, Beta is a distinctive white star with blue companions. Separated by about 7 arc seconds, almost any magnification will distinguish Beta’s 4.7 magnitude primary from its 5.2 magnitude secondary to the southeast. Now, add a little power and you’ll see the fainter secondary has its own 6.2 magnitude companion less than 3 arc seconds away to the east.

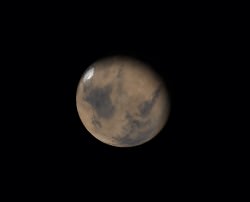

Before you call it a night, be sure to have a quick look at Mars. Right now the red planet is at opposition and can be seen from sunset until sunrise in the constellation of Leo. You may have also noticed that it is dimming slightly, too. It has now reached an estimated -1.23 magnitude. Be sure to look for wonderful features like Sytris Major and the polar caps!

Sunday, March 4 – In 1835, Giovanni Schiaparelli opened his eyes for the very first time and opened ours with his accomplishments! As the director of the Milan Observatory, Schiaparelli (and not Percival Lowell) was the fellow who popularized the term “Martian canals” somewhere around the year 1877. Far more importantly, Schiaparelli was the man who made the connection between the orbits of meteoroid streams and the orbits of comets almost eleven years earlier!

Tonight let’s turn binoculars or telescopes toward the southern lunar surface as we set out to view one of the most unusually formed craters – Schiller. Located near the lunar limb, Schiller appears as a strange gash bordered on the southwest in white and black on the northeast. This oblong depression might be the fusion of two or three craters, yet shows no evidence of crater walls on its smooth floor. Schiller’s formation still remains a mystery. Be sure to look for a slight ridge running along the spine of the crater to the north through the telescope. Larger scopes should resolve this feature into a series of tiny dots.

Let’s try our hand at Beta Orionis … the bright, blue/white star in the southwestern corner of Orion. As you may have noticed for the most part – the brighter the stars are, the closer they are. Not so Rigel! As the seventh brightest star in the sky, it breaks all the “rules” by being an amazing 900 light years away! Can you imagine what an awesome supergiant this white hot star really is? Rigel is actually one of the most luminous stars in our galaxy and if it were as close as Sirius it would be 20% as bright as tonight’s Moon! As an added bonus, most average backyard telescopes can also reveal Rigel’s 6.7 magnitude blue companion star. And if these “two” aren’t enough – note the companion is also a spectroscopic double!

Until next week? Ask for the Moon… but keep on reaching for the stars!

If you enjoy the weekly observing column, why not consider buying the fully illustrated book, The Night Sky Companion 2012. It’s available in both a softcover and Kindle format!