[/caption]

Every year from late July to mid-August, the Earth encounters a trail of debris left behind from the tail of a comet named Swift-Tuttle. This isn’t the only trail of debris the Earth encounters throughout the year, but it might be one of the most notorious as it is responsible for the annual Perseid meteor shower, one of the best and well-known yearly meteor showers.

Comet Swift-Tuttle is a very long way away from us right now, but when it last visited this part of the Solar system, it left behind a stream of debris made up of particles of dust and rock from the comet’s tail.

Earth encounters this debris field for a few weeks, reaching the densest part on the 11th to 13th August.

The tiny specs of dust and rock collide with the Earth’s atmosphere, entering at speeds ranging from 11 km/sec (25,000 mph), to 72 km/sec (160,000 mph). They are instantly vaporised, emitting bright streaks of light. These tiny particles are referred to as meteors or for the more romantic, shooting stars.

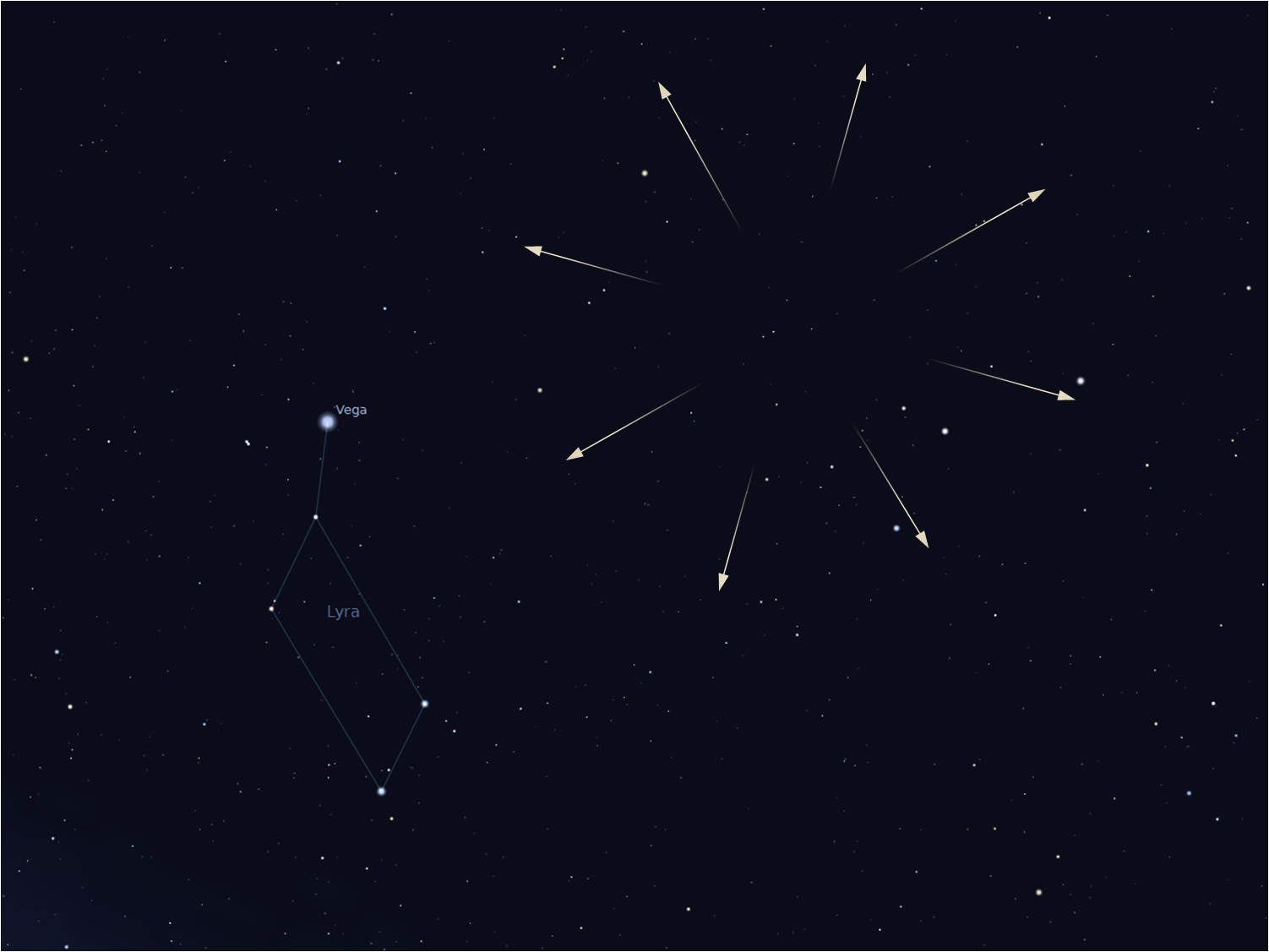

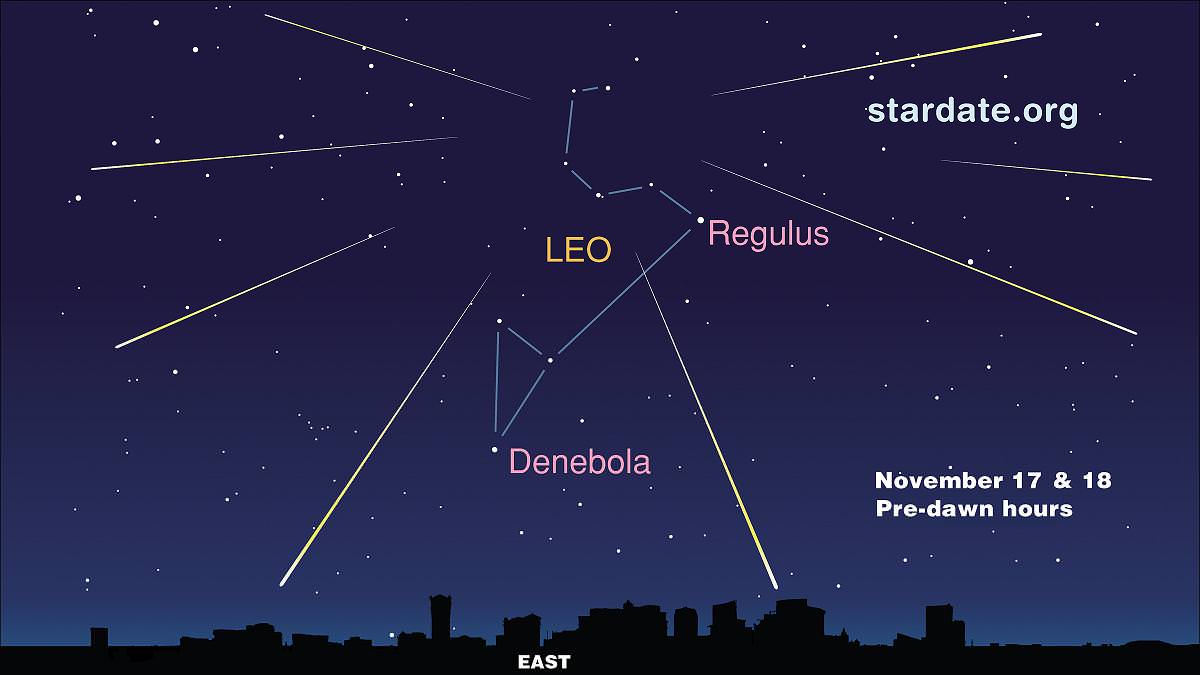

The reason the meteor shower is called the Perseid, is because the point of the sky or radiant where the meteors appear to originate from is in the constellation of Perseus, hence Perseid.

When the Perseid meteor shower reaches its peak, up to 100 meteors an hour can be seen under ideal dark sky conditions, but in 2011 this will be greatly reduced due to a full Moon at this time. Many of the fainter meteors (shooting stars) will be lost to the glare of the Moon, but do not despair as some Perseids are bright fireballs made from larger pieces of debris, that can be golf ball size or larger.

These amazingly bright meteors can last for a few seconds and can be the brightest thing in the sky. They are very dramatic and beautiful, and seeing one can be the highlight of your Perseid observing experience.

So while expectations may be low for the Perseids this year, keep an eye out for the bright ones and the fireballs. You will not be disappointed, even if you only see one!

Join in on twitter with a worldwide event with Universe Today and Meteorwatch.org just follow along using the hashtag #meteorwatch ask questions, post images, enjoy and share your Perseid Meteor Shower experience.