[/caption]

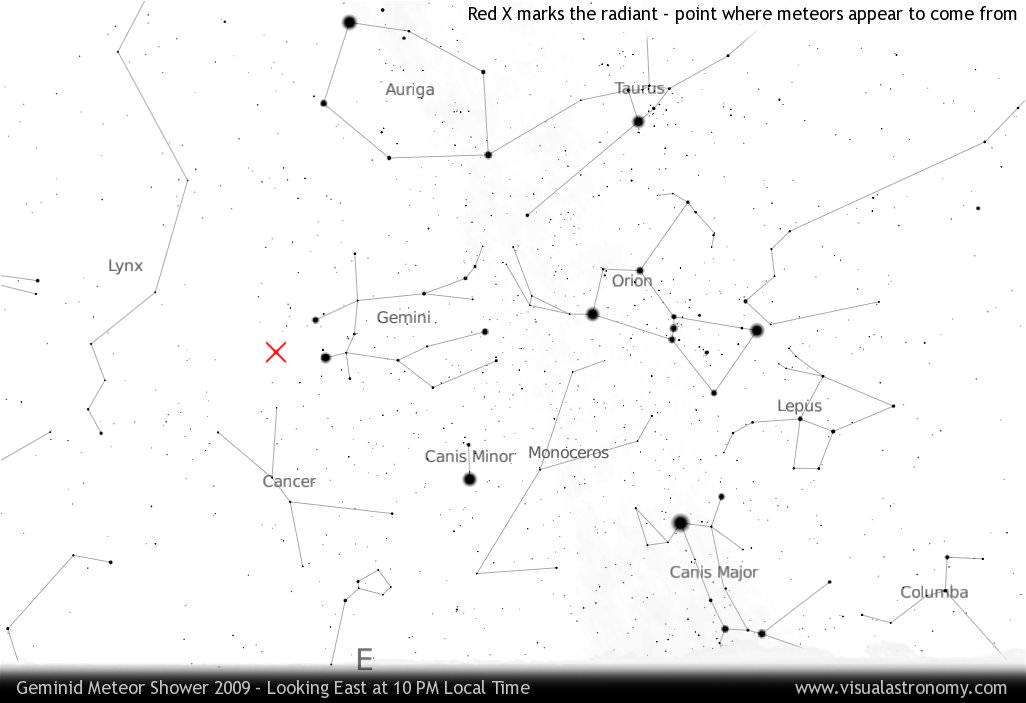

While historically, meteor showers were portents of ill omens, we know today that they are the remnants of ejecta from comets entering our atmosphere. Many showers have had their parent comets identified. But a new study is suggesting that two meteor showers, the December Monocerotids and the November Orionids, may share the same parent.

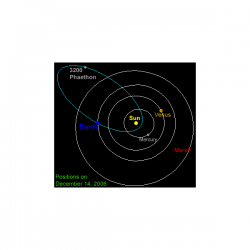

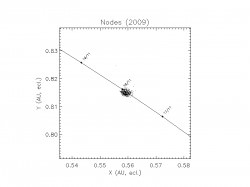

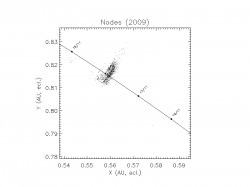

The possibility of a single comet providing multiple showers isn’t too difficult to imagine. Since comets orbit the Sun in elliptical paths there are two potential points the path can intersect Earth’s orbit: Once on the way in and once on the way out. The trouble is that comets don’t tend to orbit directly in the ecliptic plane (defined by the plane on which the Earth orbits the Sun). Thus, comets only puncture through this plane at points known as “nodes”. As a body passes from the upper half to the lower (where upper and lower are the halves defined by Earth’s north and south poles respectively) this point of intersection of the orbit with the ecliptic plane is known as the descending node. When it heads back up, this is the ascending node. If both nodes happen to lie near enough to Earth’s orbital path, the potential for two meteor showers exists. Another possibility is that orbital evolution cause the nodes to change their position and, over time, crossed Earth’s orbit at two different points.

In principle, identifying a parent comet for two showers is much simpler with the first method. In that instance, the comet still orbits in the same path (or near enough) to be conclusively identified as the progenitor. If such an instance were to arise due to orbital evolution, the case must be much more indirect since interactions with planets, even at fairly large distances, can induce large uncertainties in the orbital history.

The December Monocerotids have been associated with a comet known as C/1917 F1 Mellish. Unfortunately for the researchers, the current orbital characteristics of the comet did not feature nodes in Earth’s orbit and did not match the November Orionids. Thus, to establish a connection between the two meteor streams, the team of astronomers from Comenius University in Slovakia, looked at the characteristics of the showers. In order to track these characteristics, the team utilized a publicly available database of meteor recordings from SonotaCo which uses webcams to capture video of meteors and then compute the orbital characteristics of the debris. However, the two showers did share suspiciously similar distributions of sizes (and thus brightnesses) of meteors as well as the velocity and less so, but still notable, the eccentricity.

This led the team to suspect that the node had evolved across Earth’s orbit sweeping by once in the past to create the stream of debris that forms the November shower, and more recently, crossed our orbit to create the December shower. If this hypothesis were correct, the team expected to also find subtle differences hinting that the November shower was older. Sure enough, the November Orionids show a larger dispersion of velocities than that of the December shower.

In the future, the team plans to revise the orbital characteristics of the parent comet. While they were able to show that the precession of the orbit would allow for the situation described, it was only one of a number of possible solutions. Thus, refining the knowledge of the orbit, perhaps from archival photographic plates, would allow the team to better constrain the path and determine the orbital history sufficiently to reinforce or refute their scenario.