On Sunday, March 22, two meteor showers will grace the dark evening sky – the Camelopardalids and March Geminids. Would you like to learn more about what makes them special and why? Then let’s head out into the dark…

We’ll start first with the Camelopardalids. These have no definite peak, and a screaming fall rate of only one per hour. They do have a claim to fame however – these are the slowest meteors known – arriving at a speed of only 7 kilometers per second and activity has been historically recorded on this date. Any bright streaks you might see belonging to the Camelopardalids will appear to emanate from the north. While this might seem rather boring, any member of the Camelopardalids you might spot are anything but boring. “A search for parent bodies for 22 short-period meteoroid streams with an account of long-period planetary perturbations was carried out. Five minor body complexes are found among short-period comets, Earth-crossing asteroids and meteoroid streams.” say Y.V. Obrubov, “There are ten members in the major complex : two comets, P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 3 and P/Pons-Winnecke ; four asteroids, 1984 KD (3671), 4788 PL, 1987 SJ3, 1987 PA…” So where does the stream for the Camelopardalids fit in? Try possibly asteroid Amor (1221) and/or asteroid Selevk (3288) as part of Complex 5.

1221 Amor is the namesake of the Amor asteroids – a group of near-Earth asteroids whose orbits range between those of Earth and Mars. Amor-types often cross Mars orbital path, but not Earth’s. However, on March 12, 1932, Belgian astronomer Eugene Delporte photographed Amor as it approached Earth to within 16 million kilometers (about 40 times the distance from Earth to the Moon). This was the first time an asteroid was witnessed so close to Earth and became our virtual wake-up call to potential hazards. Not surpising, 3288 Selevk is also a planet crossing asteroid, too. According to Obrubov’s research there are 22 meteoroid swarms from bodies with orbital period of less than six years that could account for up to 104 meteor showers – 72 of which have been confirmed either photographically or by radar. “The Camelopardalids has a twin – the Gamma Aurigids.” says Obrubov, “We may therefore assume that the remnants of the parent bodies have been found for two more meteor showers. The existence of complexes of minor bodies again raises the question of the possibility of the simultaneous existence of active comets and products of disintegration – meteoroid swarms and possibly asteroids of the Apollo, Amor and Aten groups…”

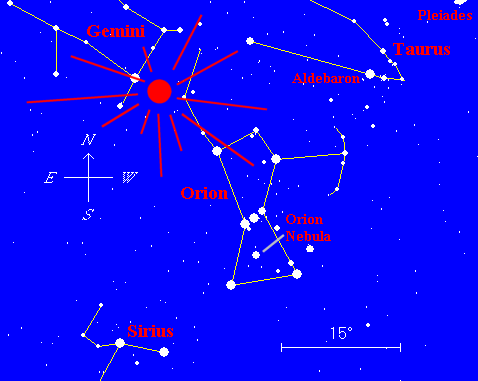

So, now we have meteors possibly coming from an asteroid, but what about the other meteor shower that occurs tonight? That’s right… the March Geminids. These were first discovered and recorded in 1973, then confirmed in 1975. With a much improved fall rate of up to 40 per hour, these slightly faster meteors will greatly increase your chance of spotting a shooting star. Like the Camelopardalids, the March Geminds are slower than average – but what causes them? Let’s turn to the work of Miroslav Plavec for an answer:

“In 1947, Whipple published new elements of the Geminid meteor shower, obtained photographically. An extremely short period, 1.65 years, moderate inclination and considerable eccentricity together make the orbit of this shower an extraordinary one both in comparison with comets and with minor planets. But, according to Hoffmeister, the existence of similar meteor showers seems to be indicated. Such a short-period meteor shower as the Geminids presents new aspects in meteor astronomy. Planetary perturbations are likely to play a great part in its nature. The study of secular perturbations is especially important, both in investigating the connection with comets, and also from the observer’s point of view; for example, Adams’ classical work on the Leonids.”

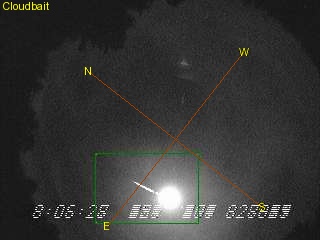

So, when do you start watching? Just as soon as the sky is good and dark at your local time. Use your own best judgement on where to loosely face based on the position of both Camelopardalis and Gemini at the time of your observation. (For most northern hemisphere locations, I would simply suggest facing roughly north and focusing your attention overhead.) Grab a friend, a blanket, a thermos… take your notes and a timepiece, too.

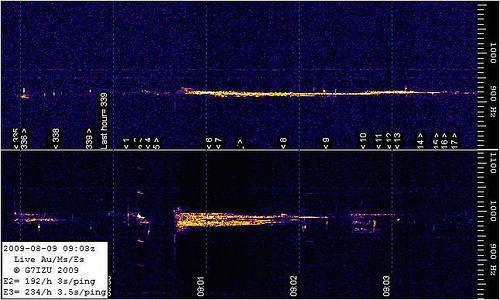

You can make an important contribution by observing when possible. Since the shower wasn’t reported until 1973 and confirmed by a high rate of activity 2 years later, scientists aren’t really sure if the Earth had passed through that particular particle stream until that time. By observing and reporting, even to sources like Universe Today, you are providing an invaluable Internet record to help determine if the stream is genuine. It the March Geminids truly are a viable annual shower, this trail might lead to an undiscovered comet.

If you wish to report your findings elsewhere, please visit the Association of Lunar and Planetary Observers (ALPO) and locate the meteor observing tab. In these pages you will also find links to information from the North American Meteor Network (NAMN), and other things to assist you like charts to understand the meteor’s magnitude, the limiting magnitude of your location, and details for recording what you see and how to fill out an observation report. While it’s certainly true you may see absolutely nothing during an hour of observing, negative observations are also important. This helps to establish if the March Geminids should be considered an annual shower or not. You may also just happen to step outside at the right time and see a flurry of activity as well. Just remember…

When opportunity knocks, you’ve got to be there to open the door!