Itching to watch a meteor shower and don’t mind getting up at an early hour? Good because this should be a great year for the annual Eta Aquarid (AY-tuh ah-QWAR-ids) shower which peaks on Thursday and Friday mornings May 5-6. While the shower is best viewed from tropical and southern latitudes, where a single observer might see between 25-40 meteors an hour, northern views won’t be too shabby. Expect to see between 10-15 per hour in the hours before dawn.

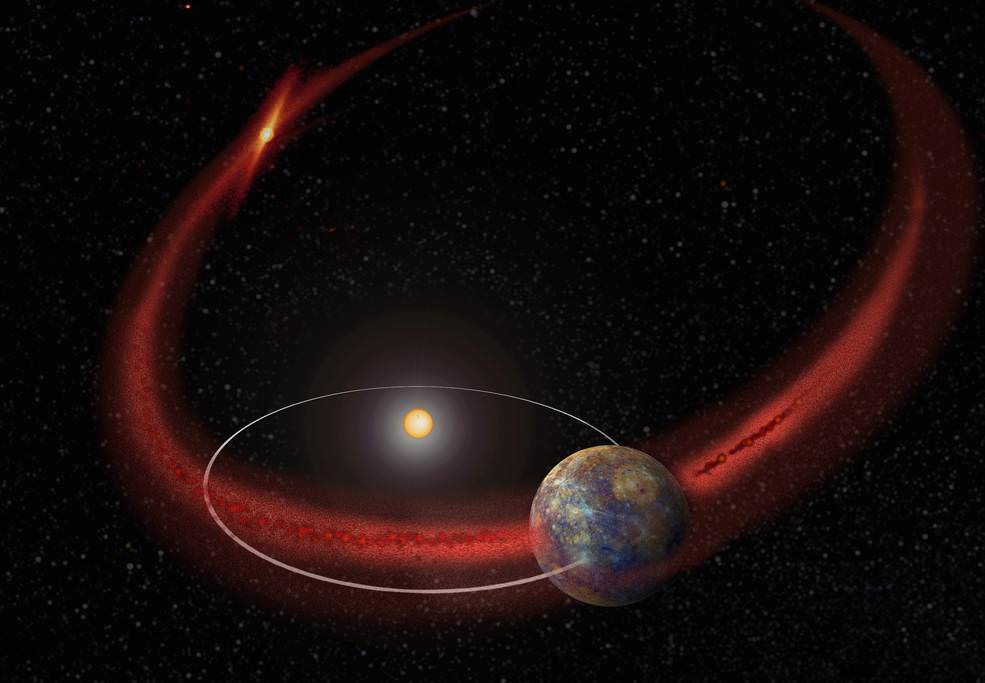

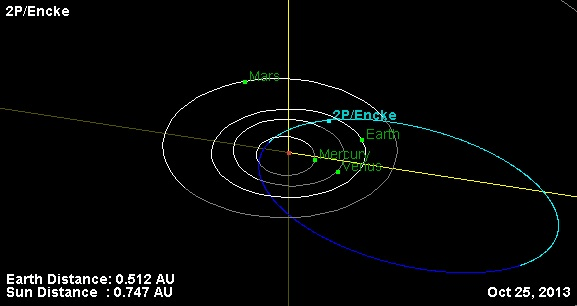

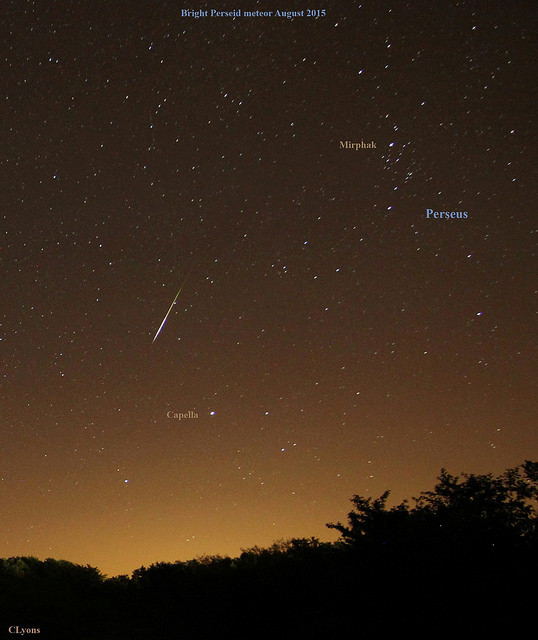

Most showers trace their parentage to a particular comet. The Perseids of August originate from dust strewn along the orbit of comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle, which drops by the inner solar system every 133 years after “wintering” for decades just beyond the orbit of Pluto.

The upcoming Eta Aquarids have the best known and arguably most famous parent of all: Halley’s Comet. Twice each year, Earth’s orbital path intersects dust and minute rock particles strewn by Halley during its cyclic 76-year journey from just beyond Uranus to within the orbit of Venus.

Our first pass through Halley’s remains happens this week, the second in late October during the Orionid meteor shower. Like bugs hitting a windshield, the grains meet their demise when they smash into the atmosphere at 147,000 mph (237,000 km/hr) and fire up for a brief moment as meteors. Most comet grains are only crumb-sized and don’t have a chance of reaching the ground as meteorites. To date, not a single meteorite has ever been positively associated with a particular shower.

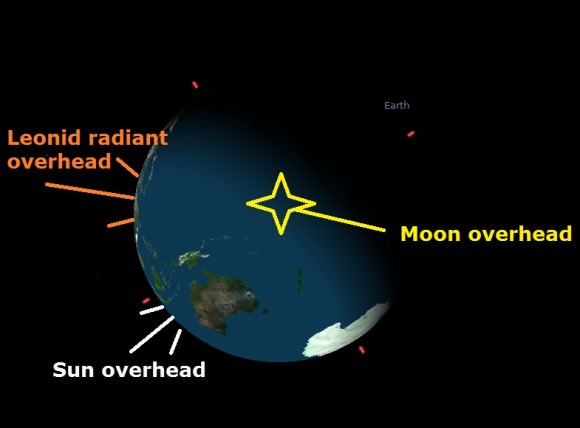

The farther south you live, the higher the shower radiant will appear in the sky and the more meteors you’ll spot. A low radiant means less sky where meteors might be seen. But it also means visits from “earthgrazers”. These are meteors that skim or graze the atmosphere at a shallow angle and take many seconds to cross the sky. Several years back, I saw a couple Eta Aquarid earthgrazers during a very active shower. One other plus this year — no moon to trouble the view, making for ideal conditions especially if you can observe from a dark sky.

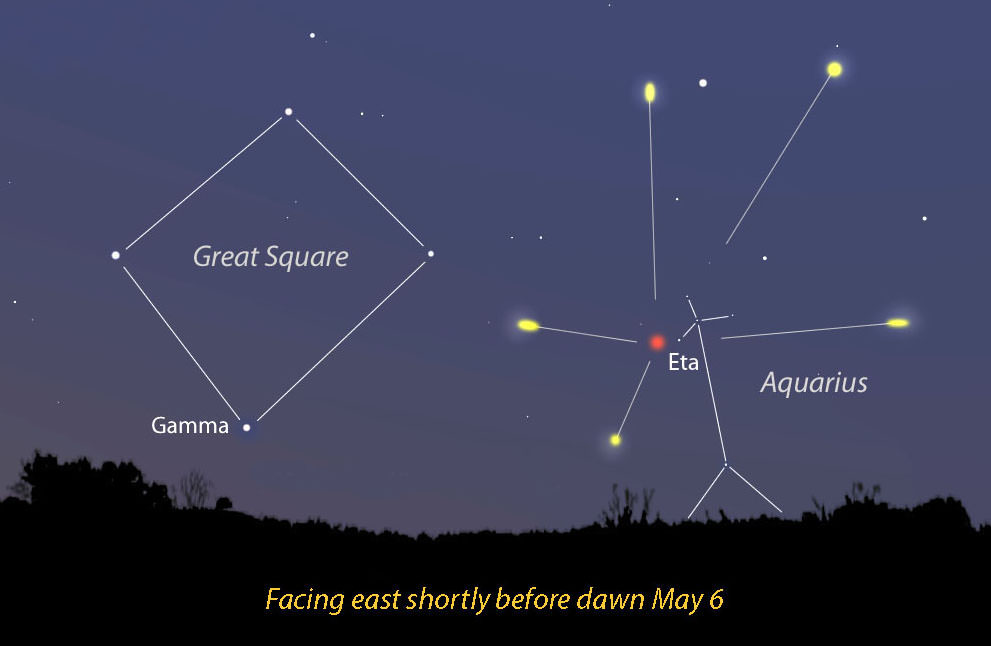

From mid-northern latitudes the radiant or point in the sky from which the meteors will appear to originate is low in the southeast before dawn. At latitude 50° north the viewing window lasts about 1 1/2 hours before the light of dawn encroaches; at 40° north, it’s a little more than 2 hours. If you live in the southern U.S. you’ll have nearly 3 hours of viewing time with the radiant 35° high.

Grab a reclining chair, face east and kick back for an hour or so between 3 and 4:30 a.m. An added bonus this spring season will be hearing the first birdsong as the sky brightens toward the end of your viewing session. And don’t forget the sights above: a spectacular Milky Way arching across the southern sky and the planets of Mars and Saturn paired up in the southwestern sky.

Meteor shower members can appear in any part of the sky, but if you trace their paths in reverse, they’ll all point back to the radiant. Other random meteors you might see are called sporadics and not related to the Eta Aquarids. Meteor showers take on the name of the constellation from which they originate.

Aquarius is home to at least two showers. This one’s called the Eta Aquarids because it emanates from near the star Eta Aquarii. An unrelated shower, the Delta Aquarids, is active in July and early August. Don’t sweat it if weather doesn’t cooperate the next couple mornings. The shower will be active throughout the weekend, too.

Happy viewing and clear skies!