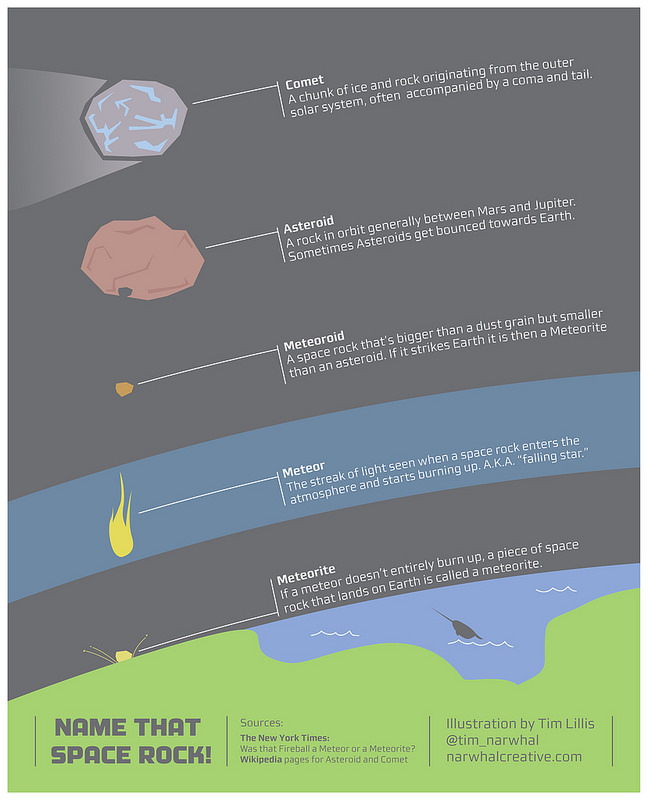

A little more than week ago a 7,000 ton, 50-foot (15-meter) wide meteoroid made an unexpected visit over Russia to become the biggest space rock to enter the atmosphere since the Tunguska impact in 1908. While scientists still debate whether it was asteroid or comet that sent a tree-flattening shockwave over the Tunguska River valley, we know exactly what fell last Friday.

Now is a fitting time to get more familiar with these extraterrestrial rocks that drop from out of nowhere.

The Russian meteoroid – the name given an asteroid fragment before it enters the atmosphere – became a brilliant meteor during its passage through the air. If a cosmic rock is big enough to withstand the searing heat and pressure of entry, fragments survive and fall to the ground as meteorites. Most of the meteors or “shooting stars” we see on a clear night are bits of rock the size of apple seeds. When they strike the upper atmosphere at tens of thousands of miles an hour, they vaporize in a flash of light. Case closed. But the one that boomed over the city of Chelyabinsk was big enough to to survive its last trip around the Sun and sprinkle the ground with meteorites.

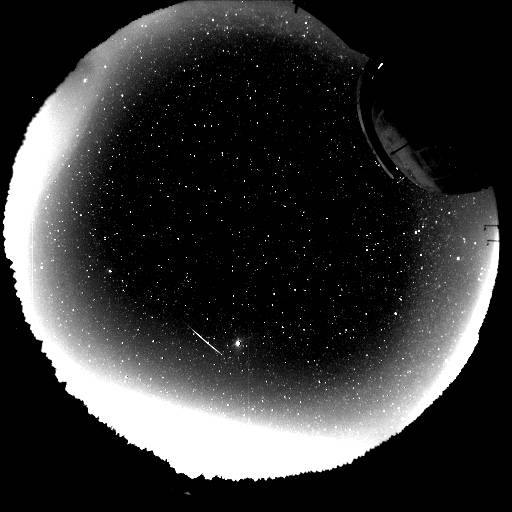

Ah, but the Russian fireball didn’t get off the hook that easy. The overwhelming air pressure at those speeds combined with re-entry temperatures around 3,000 degrees F (1,650 C) shattered the original space rock into many pieces. You can see the dual trails created by two of the larger hunks in the photo above.

Scientists at Urals Federal University in Yekaterinburg examined 53 small meteorite fragments deposited around a hole in ice-covered Chebarkul Lake 48 miles (77 km) west of Chelyabinsk the following day. Chemical analysis revealed the stones contained 10% iron-nickel metal along with other minerals commonly found in stony meteorites. Since then, hundreds of fragments have been dug out of the snow by people in surrounding villages. As specimens continue to be recovered and analyzed, here’s an overview — and a look at what we know — of these space rocks that pay us a visit from time to time.

How many times has a meteor taken your breath away? A brilliant fireball streaking across the night sky ranks among the most memorable astronomical sights most of us will ever see. Like objects in your side view mirror, meteors appear closer than they really are. And it’s all the more true when they’re exceptionally bright. Studies show however that meteors burn up at least 50 miles (80 km) overhead. If big enough to remain intact and land on the ground, the fragments go completely dark 5-12 miles (8-19 km) high during the “dark flight” phase. A meteor passing overhead would be at the minimum distance of about 50 miles (80 km) from the observer.

Since most sightings are well off toward one direction or another, you have to add your horizontal distance to the meteor’s height to get a true distance. While some meteors are bright enough to trick us into thinking they landed just over the next hill, nearly all are many miles away. Even the Russian meteor, which put on a grand show and blasted the city of Chelyabinsk with a powerful shock wave, dropped fragments dozens of miles to the west. We lack the context to appreciate meteor distances, perhaps unconsciously comparing what we see to an aerial fireworks display.

Very cute Youtube video of Sasha Zarezina, 8, who lives in a small Siberian village, as she hunts for meteorite fragments in the snow after Friday’s meteor over Russia. Credit: Ben Solomon/New York Times

An estimated 1,000 tons (907 metric tons) to more than 10,000 tons (9,070 MT) of material from outer space lands on Earth every day delivered free of charge from the main Asteroid Belt. Crack-ups between asteroids in the distant past are nudged by Jupiter into orbits that cross that of Earth’s. Most of the stuff rains down as micrometeoroids, bits of grit so small they’re barely touched by heating as they gently waft their way to the ground. Many larger pieces – genuine meteorites – make it to Earth but are missed by human eyes because they fall in remote mountains, deserts and oceans. Since over 70% of Earth’s surface’s is water, think of all the space rocks that must sink out of sight forever.

About 6-8 times a year however, a meteorite-producing fireball streaks over a populated area of the world. Using eyewitness reports of time, direction of travel along with more modern tools like video surveillance cameras and Doppler weather radar, which can ping the tracks of falling meteorites, scientists and meteorite hunters have a great many clues on where to look for space rocks.

Since most meteorites break into pieces in mid-air, the fragments are dispersed over the ground in a large oval called the strewnfield. The little pieces fall first and land at the near end of the oval; the bigger chunks travel farthest and fall at the opposite end.

When a new potential meteorite falls, scientists are eager to get a hold of pieces as soon as possible. Back in the lab, they measure short-lived elements called radionuclides created when high-energy cosmic rays in space alter elements in the rock. Once the rock lands on Earth, creation of these altered elements stops. The proportions of radionuclides tell us how long the rock traveled through space after it was ejected by impact from its mother asteroid. If a meteorite could write a journal, this would be it.

Other tests that examine the decay of radioactive elements like uranium into lead tells us the age of the meteorite. Most are 4.57 billion years old. Hold a meteorite and you’ll be whisked back to a time before the planets even existed. Imagine no Earth, no Jupiter.

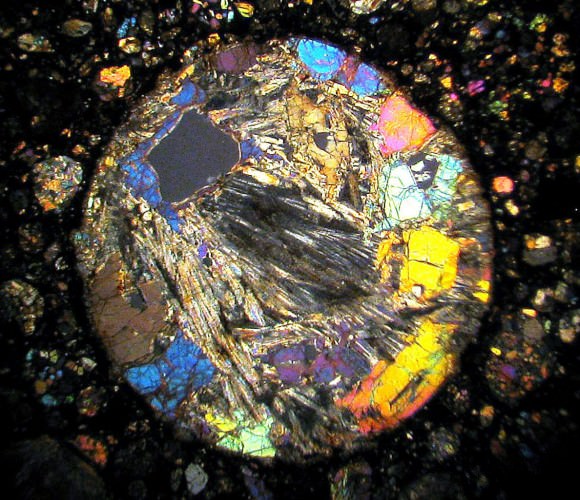

Many meteorites are jam-packed with tiny rocky spheres called chondrules. While their origin is still a topic of debate, chondrules (KON-drools) likely formed when blots of dust in the solar nebula were flash-heated by the young sun or perhaps by powerful bolts of static electricity. Sudden heating melted the motes into chondrules which quickly solidified. Later, chondrules agglomerated into larger bodies that ultimately grew into planets through mutual gravitational attraction. You can always count on gravity to get the job done. Oh, just so you know, meteorites are no more radioactive than many common Earth rocks. Both contain trace amounts of radioactive elements at trifling levels.

Meteorites fall into three broad categories – irons (mostly metallic iron with smaller amounts of nickel), stones (composed of rocky silicates like olivine, pyroxene and plagioclase and iron-nickel metal in form of tiny flakes) and stony-irons (a mix of iron-nickel metal and silicates). The stony-irons are broadly subdivided into mesosiderites, chunky mixes of metal and rock, and pallasites.

Pallasites are the beauty queens of the meteorite world. They contain a mix of pure olivine crystals, better known as the semi-precious gemstone peridot, in a matrix of iron-nickel metal. Sliced and polished to a gleaming finish, a pallasite wouldn’t look out of place dangling from the neck of an Oscar winner. About 95% of all found or seen-to-fall meteorites are the stony variety, 4.4% are irons and 1% stony-irons.

Earth’s atmosphere is no friend to space rocks. Collecting them early prevents damage by the two things most responsible for keeping us alive: water and oxygen. Unless a meteorite lands in a dry desert environment like the Sahara or the “cold desert” of Antarctica, most are easy prey to the elements. I’ve seen meteorites collected and sliced open within a week after a fall that already show brown stains from rusting nickel-iron. Antarctica is off-limits to all but professional scientists, but thanks to amateur collectors’ efforts in the Sahara Desert, Oman and other regions, thousands of meteorites including some of the rarest types, have come to light in recent years.

Hunters share their finds with museums, universities and through outreach efforts in the schools. A portion of the material is sold to other collectors to finance future expeditions, pay for plane tickets and sit down to a good meal after the hunt. Finding a meteorite of your own is hard but rewarding work. If you’d like to have a go at it, here’s a basic checklist of qualities that separate space rocks from Earth rocks:

* Attracts a magnet. Most meteorites – even stony ones – contain iron.

* Most are covered with a matt-black, slightly bumpy fusion crust that colors dark brown with age. Look for hints of rounded chondrules or tiny bits of metal sticking up through the crust.

* Aerodynamic shape from its flight through the atmosphere, but be wary of stream-eroded rocks which appear superficially similar

* Some are dimpled with small thumbprint-like depressions called regmaglypts. These form when softer materials melt and stream away during atmospheric entry. Some meteorites also display hairline-thin, melted-rock flow lines rippling across their exteriors.

Should your rock passes the above tests, file off an edge and look inside. If the interior is pale with shining flecks of pure metal (not mineral crystals), your chances are looking better. But the only way to be certain of your find is to send off a piece to a meteorite expert or lab that does meteorite analysis. Industrial slag with its bubbly crust and dark, smooth volcanic rocks called basalts are the most commonly found meteor-wrongs. We imagine that meteorites must have bubbly crust like a cheese pizza; after all, they’ve been oven-baked by the atmosphere, right? Nope. Heating only happens in the outer millimeter or two and crusts are generally quite smooth.

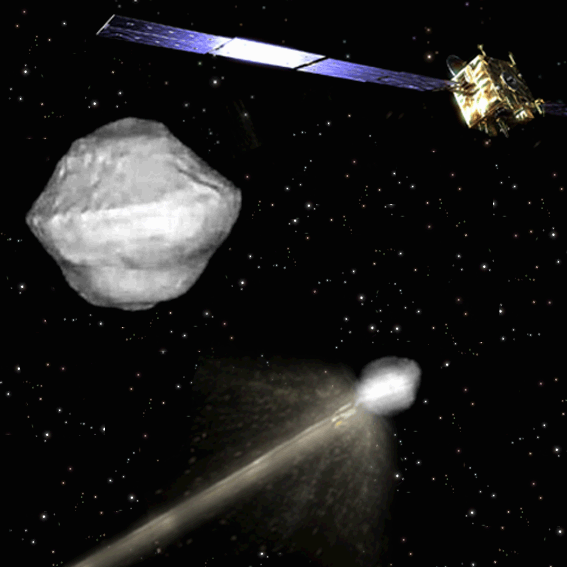

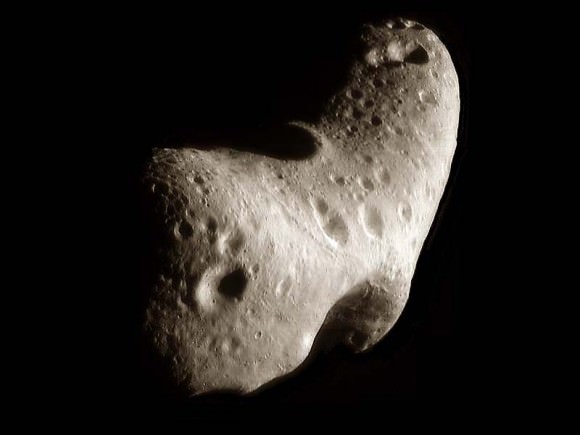

Stony meteorites are further subdivided into two broad types – chondrites, like the Russian fall, and achondrites, so-called because they lack chondrules. Achondrites are igneous rocks formed from magma deep within an asteroid’s crust and lava flows on the surface. Some eucrites (YOU-crites), the most common type of achondrite, likely originated as fragments shot into space from impacts on Vesta. Measurements by NASA’s Dawn space mission, which orbited the asteroid from July 2011 to September 2012, have found great similarities between parts of Vesta’s crust and eucrites found on Earth.

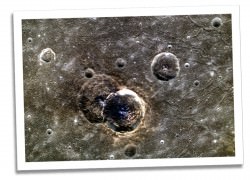

We also have meteorites from Mars and the Moon. They got here the same way the rest of them did; long-ago impacts excavated crustal rocks and sent them flying into space. Since we’ve studied moon rocks brought back by the Apollo missions and sampled Mars atmosphere with a variety of landers, we can compare minerals and gases found inside potential moon and Mars meteorites to confirm their identity.

Scientists study space rocks for clues of the Solar System’s origin and evolution. For the many of us, they provide a refreshing “big picture” perspective on our place in the Universe. I love to watch eyes light up with I pass around meteorites in my community education astronomy classes. Meteorites are one of the few ways students can “touch” outer space and feel the awesome span of time that separates the origin of the Solar System and present day life.

And even though the ratio of calcium silicates is higher than what’s found on Mercury today, Irving speculates that the fragments of NWA 7325 could have come from a deeper part of Mercury’s crust, excavated by a powerful impact event and launched into space, eventually finding their way to Earth.

And even though the ratio of calcium silicates is higher than what’s found on Mercury today, Irving speculates that the fragments of NWA 7325 could have come from a deeper part of Mercury’s crust, excavated by a powerful impact event and launched into space, eventually finding their way to Earth.