One of the best meteor showers of the year – the Geminids – are about to peak. If you’ve got clear skies, head out on the evening of December 13th, and you could see a few meteors an hour. Unlike most meteor showers, the source of the Geminids is a bit of a mystery, since the dust doesn’t seem to originate from a comet. A small asteroid called 3200 Phaethon has been discovered in the right orbit, but astronomers aren’t sure how it could be generating enough dust to cause such beautiful meteor showers.

One of the best meteor showers of the year – the Geminids – are about to peak. If you’ve got clear skies, head out on the evening of December 13th, and you could see a few meteors an hour. Unlike most meteor showers, the source of the Geminids is a bit of a mystery, since the dust doesn’t seem to originate from a comet. A small asteroid called 3200 Phaethon has been discovered in the right orbit, but astronomers aren’t sure how it could be generating enough dust to cause such beautiful meteor showers.

Continue reading “Watch for the Geminids on Wednesday”

Organic Material Found in an Ancient Meteorite

NASA researchers have discovered organic material inside a meteorite the recently fell in Canada’s Tagish Lake. The meteorite is especially valuable because scientists collected it shortly after it crashed in 2000, ensuring it wasn’t contaminated by local bacteria. The meteorite seems to contain many small hollow organic globules, which probably formed in the cold molecular cloud of gas and dust that gave birth to the Solar System. Meteorites like this have been falling to Earth for billions of years, and probably seeded the early planet with organic material.

Continue reading “Organic Material Found in an Ancient Meteorite”

Leonid Meteor Shower: November 19, 2006

One of the best meteor showers of the year is about to get rolling, so make sure you mark your calendar. The Leonid Meteor Shower will be peaking on Sunday, November 19, 2006, and you might be able to see as many as 100 meteors an hour. Find the darkest possible skies that you can, and wait until the constellation Leo is highest in the sky. Observers in western Europe, Africa, Brazil and the eastern parts of North America will get the best view this year.

Continue reading “Leonid Meteor Shower: November 19, 2006”

The Link Between Asteroids and Meteorites

In theory, asteroids and meteorites are made of the same basic elements; it’s just that asteroids are much much bigger. But scientists had always found troubling chemical differences between the two kinds of objects. New data gathered by the Japanese spacecraft Hayabusa, which recently visited the near-Earth asteroid Itokawa, shows that there’s a good reason for the difference. It’s the long-term effect of space weathering – solar and cosmic radiation – that changes the surface of asteroids to look different from meteorites.

Continue reading “The Link Between Asteroids and Meteorites”

Washed Out Perseids Will Peak on Friday

One of the best meteor showers of the year – the Perseids – will get washed out by a nearly full Moon this year. But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try and enjoy them anyway. The Moon will be 87% full on Friday, August 11, rising after 10:00pm. Head out after it goes dark, and see if you can spot an Earth grazer; a special kind of meteor that can be very bright and slow, leaving a dramatic tail. After 10:00pm, only the brightest meteors will be visible. 2007 will be much better, when it’ll be a moonless sky.

Continue reading “Washed Out Perseids Will Peak on Friday”

Meteoroid Strike on the Moon

NASA researchers fortunate enough to be recording the Moon through a 10″ telescope equipped with a video camera when they saw a meteoroid strike. The spacerock was only 25 cm (10 inches) wide, but it released 17 billion joules of kinetic energy; the same as 4 tons of TNT. The resulting flash was quick, only lasting 4/10ths of a second, but it was powerful enough to carve out a crater 14 metres (46 feet) wide.

Continue reading “Meteoroid Strike on the Moon”

New Technique for Finding Organic Molecules in Meteorites

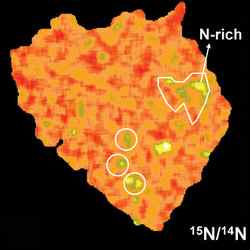

Tiny particles of meteorites with portions of nitrogen and hydrogen. Image credit: Henner Busemann. Click to enlarge

When the Solar System first formed billions of years ago, organic molecules – the building blocks of life – were churned into the mix that went on to create the planets. Scientists from the Carnegie Institution have developed a technique to find these tiny organic particles hidden inside meteorites. These meteorites have survived since the formation of the Solar System, so it allows scientists to track the distribution of organic material and the processes they went through as the planets formed.

Like an interplanetary spaceship carrying passengers, meteorites have long been suspected of ferrying relatively young ingredients of life to our planet. Using new techniques, scientists at the Carnegie Institution’s Department of Terrestrial Magnetism have discovered that meteorites can carry other, much older passengers as well-primitive, organic particles that originated billions of years ago either in interstellar space, or in the outer reaches of the solar system as it was beginning to coalesce from gas and dust. The study shows that the parent bodies of meteorites-the large objects from the asteroid belt-contain primitive organic matter similar to that found in interplanetary dust particles that might come from comets. The finding provides clues about how organic matter was distributed and processed in the solar system during this long-gone era. The work is published in the May 5, 2006, issue of Science.

“Atoms of different elements come in different forms, or isotopes, and the relative proportions of these depend on the environmental conditions in which their carriers formed, such as the heat encountered, chemical reactions with other elements, and so forth,” explained lead author Henner Busemann. “In this study we looked at the relative amounts of different isotopes of hydrogen (H) and nitrogen (N) associated with tiny particles of insoluble organic matter to determine the processes that produced the most pristine type of meteorites known. The insoluble material is very hard to break down chemically and survives even very harsh acid treatments.”

The researchers used a microscopic imaging technique to analyze the isotopic composition of insoluble organic matter from six carbonaceous chondrite meteorites-the oldest type known. The relative proportion of isotopes of nitrogen and hydrogen associated with the insoluble organic matter act as “fingerprints” and can reveal how and when the carbon was formed. The isotope of nitrogen that is most often found in nature is 14N; its heavier sibling is 15N. Differing amounts of 15N, in addition to a heavier form of hydrogen called deuterium, (D), allow researchers to tell if a particle is relatively unaltered from the time when the solar system was first forming.

“The tell-tale signs are lots of deuterium and 15N chemically bonded to carbon,” commented co-author Larry Nittler. “We have known for some time, for instance, that interplanetary dust particles (IDP), collected from high-flying airplanes in the upper atmosphere, contain huge excesses of these isotopes, probably indicating vestiges of organic material that formed in the interstellar medium. The IDPs have other characteristics indicating that they originated on bodies-perhaps comets-that have undergone less severe processing than the asteroids from which meteorites originate.”

The scientists found that some meteorite samples, when examined at the same tiny scales as interplanetary dust particles, actually have similar or even higher abundances of 15N and D than those reported for IDPs. “It’s amazing that pristine organic molecules associated with these isotopes were able to survive the harsh and tumultuous conditions present in the inner solar system when the meteorites that contain them came together,” reflected co-author Conel Alexander. “It means that the parent bodies-the comets and asteroids-of these seemingly different types of extraterrestrial material are more similar in origin than previously believed.”

“Before, we could only explore minute samples from IDPs. Our discovery now allows us to extract large amounts of this material from meteorites, which are large and contain several percent of carbon, instead of from IDPs, which are on the order of a million million times less massive. This advancement has opened up an entirely new window on studying this elusive period of time,” concluded Busemann.

Original Source: Carnegie Institution

Microscopic Tunnels Carved by Martian Microbes?

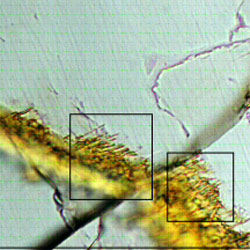

A thin slice of the Nakhla meteor. Image credit: OSU Click to enlarge.

Bacteria seem to live anywhere there’s water. One class of bacteria are known to burrow through igneous rock feeding on iron and other chemicals, and leaving a tiny tunnel behind them. Now researchers have found similar tunnels in a meteorite believed to have originated on Mars called the Nakhla meteorite. This adds additional data to the mounting evidence that Mars was wet in the distant past, and gives the tantalizing possibility that it was inhabited with life.

A new study of a meteorite that originated from Mars has revealed a series of microscopic tunnels that are similar in size, shape and distribution to tracks left on Earth rocks by feeding bacteria.

And though researchers were unable to extract DNA from the Martian rocks, the finding nonetheless adds intrigue to the search for life beyond Earth.

Results of the study were published in the latest edition of the journal Astrobiology.

Martin Fisk, a professor of marine geology in the College of Oceanic and Atmospheric Sciences at Oregon State University and lead author of the study, said the discovery of the tiny burrows do not confirm that there is life on Mars, nor does the lack of DNA from the meteorite discount the possibility.

“Virtually all of the tunnel marks on Earth rocks that we have examined were the result of bacterial invasion,” Fisk said. “In every instance, we’ve been able to extract DNA from these Earth rocks, but we have not yet been able to do that with the Martian samples.

“There are two possible explanations,” he added. “One is that there is an abiotic way to create those tunnels in rock on Earth, and we just haven’t found it yet. The second possibility is that the tunnels on Martian rocks are indeed biological in nature, but the conditions are such on Mars that the DNA was not preserved.”

More than 30 meteorites that originated on Mars have been identified. These rocks from Mars have a unique chemical signature based on the gases trapped within. These rocks were “blasted off” the planet when Mars was struck by asteroids or comets and eventually these Martian meteorites crossed Earth’s orbit and plummeted to the ground.

One of these is Nakhla, which landed in Egypt in 1911, and provided the source material for Fisk’s study. Scientists have dated the igneous rock fragment from Nakhla – which weighs about 20 pounds – at 1.3 billion years in age. They believe that the rock was exposed to water about 600 million years ago, based on the age of clay found inside the rocks.

“It is commonly believed that water is a necessary ingredient for life,” Fisk said, “so if bacteria laid down the tunnels in the rock when the rock was wet, they may have died 600 million years ago. That may explain why we can’t find DNA – it is an organic compound that can break down.”

Other authors on the paper include Olivia Mason, an OSU graduate student; Radu Popa, of Portland State University; Michael Storrie-Lombardi, of the Kinohi Institute in Pasadena, Calif.; and Edward Vicenci, from the Smithsonian Institution.

Fisk and his colleagues have spent much of the past 15 years studying microbes that can break down igneous rock and live in the obsidian-like volcanic glass. They first identified the bacteria through their signature tunnels then were able to extract DNA from the rock samples – which have been found in such diverse environments on Earth as below the ocean floor, in deserts and on dry mountaintops.

They even found bacteria 4,000 feet below the surface in Hawaii that they reached by drilling through solid rock.

In all of these Earth rock samples that contain tunnels, the biological activity began at a fracture in the rock or the edge of a mineral where the water was present. Igneous rocks are initially sterile because they erupt at temperatures exceeding 1,000 degrees C. – and life cannot establish itself until the rocks cool. Bacteria may be introduced into the rock via dust or water, Fisk pointed out.

“Several types of bacteria are capable of using the chemical energy of rocks as a food source,” he said. “One group of bacteria in particular is capable of getting all of its energy from chemicals alone, and one of the elements they use is iron – which typically comprises 5 to 10 percent of volcanic rock.”

Another group of OSU researchers, led by microbiologist Stephen Giovannoni, has collected rocks from the deep ocean and begun developing cultures to see if they can replicate the rock-eating bacteria. Similar environments usually produce similar strains of bacteria, Fisk said, with variable factors including temperature, pH levels, salt levels, and the presence of oxygen.

The igneous rocks from Mars are similar to many of those found on Earth, and virtually identical to those found in a handful of environments, including a volcanic field found in Canada.

One question the OSU researchers hope to answer is whether the bacteria begin devouring the rock as soon as they are introduced. Such a discovery would help them estimate when water – and possibly life – may have been introduced on Mars.

Original Source: OSU News Release

Look Up, You Might See a Fireball

Taurid fireball photographed Oct. 28, 2005. Image credit: Hiroyuki Iida. Click to enlarge.

“I thought some wise guy was shining a spotlight at me,” says Josh Bowers of New Germany, Pennsylvania. “Then I realized what it was: a fireball in the southern sky. I was doing some backyard astronomy around 9 p.m. on Halloween (Oct. 31, 2005), and this meteor was so bright it made me lose my night vision.”

Bowers wasn’t the only one who saw the fireball. Lots of people were outdoors Trick or Treating. They saw what Bowers saw … and more. Before the night was over, reports of meteors “brighter than a full moon” were streaming in from coast to coast.

Astronomers have taken to calling these the “Halloween fireballs.” But there’s more to it than Halloween. The display has been going on for days.

On Oct. 30, for example, Bill Plaskon of Jonesport, Maine, was “observing Mars through a 10-inch telescope at 10:04 p.m. EST when a brilliant fireball lit up the sky and left a short corkscrew-like smoke trail that lasted about 1 minute.”

On Oct 28, Lance Taylor of Edmonton, Alberta, woke up early to go fishing with five friends. At about 6 a.m. they “noticed a nice fireball. Then 20 minutes later there was another,” he says.

On Nov. 2 in the Netherlands, “The sky lit up very bright,” reports Koen Miskotte. “In the corner of my eye I saw a fireball about as bright [as a crescent moon].”

And so on?.

What’s happening? “People are probably seeing the Taurid meteor shower,” says meteor expert David Asher of the Armagh Observatory in Northern Ireland.

Every year in late October and early November, he explains, Earth passes through a river of space dust associated with Comet Encke. Tiny grains hit our atmosphere at 65,000 mph. At that speed, even a tiny smidgen of dust makes a vivid streak of light–a meteor–when it disintegrates. Because these meteors shoot out of the constellation Taurus, they’re called Taurids.

Most years the shower is weak, producing no more than five rather dim meteors every hour. But occasionally, the Taurids put on quite a show. Fireballs streak across the sky, ruining night vision and interrupting fishing trips.

Asher thinks 2005 could be such a year.

According to Asher, the fireballs come from a swarm of particles bigger than the usual dust grains. “They’re about the size of pebbles or small stones,” he says. (It may seem unbelievable that a pebble can produce a fireball as bright as the Moon, but remember, these things hit the atmosphere at very high speed.) The rocky swarm moves within the greater Taurid dust stream, sometimes hitting Earth, sometimes not.

“In the early 1990s, when Victor Clube was supervising my PhD work on Taurids,” recalls Asher, “we came up with this model of a swarm within the Taurid stream to explain enhanced numbers of bright Taurid meteors being observed in particular years.” They listed “swarm years” in a 1993 paper in the Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society and predicted an encounter in 2005.

It seems to be happening.

When should you look? You might see a fireball flitting across the sky any time Taurus is above the horizon. At this time of year, the Bull rises in the east at sunset. The odds of seeing a bright meteor improve as the constellation climbs higher. By midnight, Taurus is nearly overhead, so that is a particularly good time.

According to the International Meteor Organization, the Taurid shower peaks between Nov. 5th and Nov. 12th. “Earth takes a week or two to traverse the swarm,” notes Asher. “This comparatively long duration means you don’t get spectacular outbursts like a Leonid meteor storm.” It’s more of a slow drizzle–“maybe one every few hours,” says Asher.

A drizzle of fireballs, however, is nothing to sneeze at. So keep an eye on the sky this month for Taurids.

Original Source: Science@NASA Story

Meteorites Could Have Supplied the Earth with Phosphorus

Image credit: University of Arizona

University of Arizona scientists have discovered that meteorites, particularly iron meteorites, may have been critical to the evolution of life on Earth.

Their research shows that meteorites easily could have provided more phosphorus than naturally occurs on Earth — enough phosphorus to give rise to biomolecules which eventually assembled into living, replicating organisms.

Phosphorus is central to life. It forms the backbone of DNA and RNA because it connects these molecules’ genetic bases into long chains. It is vital to metabolism because it is linked with life’s fundamental fuel, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the energy that powers growth and movement. And phosphorus is part of living architecture ? it is in the phospholipids that make up cell walls and in the bones of vertebrates.

“In terms of mass, phosphorus is the fifth most important biologic element, after carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen,” said Matthew A. Pasek, a doctoral candidate in UA’s planetary sciences department and Lunar and Planetary Laboratory.

But where terrestrial life got its phosphorus has been a mystery, he added.

Phosphorus is much rarer in nature than are hydrogen, oxygen, carbon, and nitrogen.

Pasek cites recent studies that show there’s approximately one phosphorus atom for every 2.8 million hydrogen atoms in the cosmos, every 49 million hydrogen atoms in the oceans, and every 203 hydrogen atoms in bacteria. Similarly, there’s a single phosphorus atom for every 1,400 oxygen atoms in the cosmos, every 25 million oxygen atoms in the oceans, and 72 oxygen atoms in bacteria. The numbers for carbon atoms and nitrogen atoms, respectively, per single phosphorus atom are 680 and 230 in the cosmos, 974 and 633 in the oceans, and 116 and 15 in bacteria.

“Because phosphorus is much rarer in the environment than in life, understanding the behavior of phosphorus on the early Earth gives clues to life’s orgin,” Pasek said.

The most common terrestrial form of the element is a mineral called apatite. When mixed with water, apatite releases only very small amounts of phosphate. Scientists have tried heating apatite to high temperatures, combining it with various strange, super-energetic compounds, even experimenting with phosphorous compounds unknown on Earth. This research hasn’t explained where life’s phosphorus comes from, Pasek noted.

Pasek began working with Dante Lauretta, UA assistant professor of planetary sciences, on the idea that meteorites are the source of living Earth’s phosphorus. The work was inspired by Lauretta’s earlier experiments that showed that phosphorus became concentrated at metal surfaces that corroded in the early solar system.

“This natural mechanism of phosphorus concentration in the presence of a known organic catalyst (such as iron-based metal) made me think that aqueous corrosion of meteoritic minerals could lead to the formation of important phosphorus-bearing biomolecules,” Lauretta said.

“Meteorites have several different minerals that contain phosphorus,” Pasek said. “The most important one, which we’ve worked with most recently, is iron-nickel phosphide, known as schreibersite.”

Schreibersite is a metallic compound that is extremely rare on Earth. But it is ubiquitous in meteorites, especially iron meteorites, which are peppered with schreibersite grains or slivered with pinkish-colored schreibersite veins.

Last April, Pasek, UA undergraduate Virginia Smith, and Lauretta mixed schriebersite with room-temperature, fresh, de-ionized water. They then analyzed the liquid mixture using NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance.

“We saw a whole slew of different phosphorus compounds being formed,” Pasek said. “One of the most interesting ones we found was P2-O7 (two phorphorus atoms with seven oxygen atoms), one of the more biochemically useful forms of phosphate, similar to what’s found in ATP.”

Previous experiments have formed P2-07, but at high temperature or under other extreme conditions, not by simply dissolving a mineral in room-temperature water, Pasek said.

“This allows us to somewhat constrain where the origins of life may have occurred,” he said. “If you are going to have phosphate-based life, it likely would have had to occur near a freshwater region where a meteorite had recently fallen. We can go so far, maybe, as to say it was an iron meteorite. Iron meteorites have from about 10 to 100 times as much schreibersite as do other meteorites.

“I think meteorites were critical for the evolution of life because of some of the minerals, especially the P2-07 compound, which is used in ATP, in photosynthesis, in forming new phosphate bonds with organics (carbon-containing compounds), and in a variety of other biochemical processes,” Pasek said.

“I think one of the most exciting aspects of this discovery is the fact that iron meteorites form by the process of planetesimal differentiation,” Lauretta said. That is, the building-blocks of planets, called planestesmals, form both a metallic core and a silicate mantle. Iron meteorites represent the metallic core, and other types of meteorites, called achondrites, represent the mantle.

“No one ever realized that such a critical stage in planetary evolution could be coupled to the origin of life,” he added. “This result constrains where, in our solar system and others, life could originate. It requires an asteroid belt where planetesimals can grow to a critical size ? around 500 kilometers in diameter ? and a mechanism to disrupt these bodies and deliver them to the inner solar system.”

Jupiter drives the delivery of planetesimals to our inner solar system, Lauretta said, thereby limiting the chances that outer solar system planets and moons will be supplied with the reactive forms of phosphorus used by biomolecules essential to terrestrial life.

Solar systems that lack a Jupiter-sized object that can perturb mineral-rich asteroids inward toward terrestrial planets also have dim prospects for developing life, Lauretta added.

Pasek is talking about the research today (Aug. 24) at the 228th American Chemical Society national meeting in Philadelphia. The work is funded by the NASA program, Astrobiology: Exobiology and Evolutionary Biology.

Original Source: UA News Release