What if our Solar System had another generation of planets that formed before, or alongside, the planets we have today? A new study published in Nature Communications on April 17th 2018 presents evidence that says that’s what happened. The first-generation planets, or planet, would have been destroyed during collisions in the earlier days of the Solar System and much of the debris swept up in the formation of new bodies.

This is not a new theory, but a new study brings new evidence to support it.

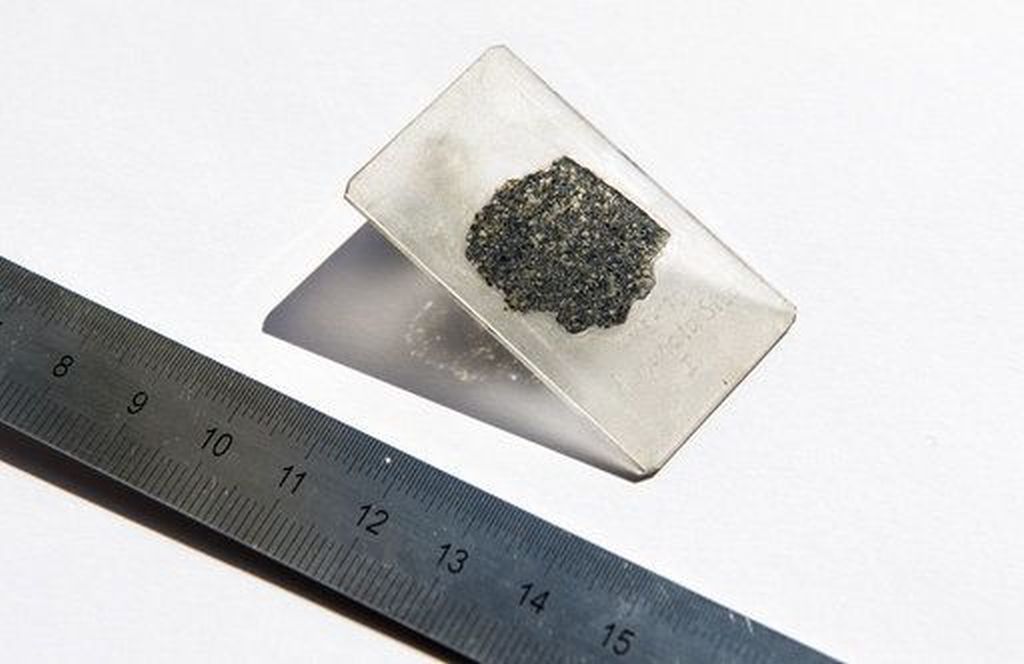

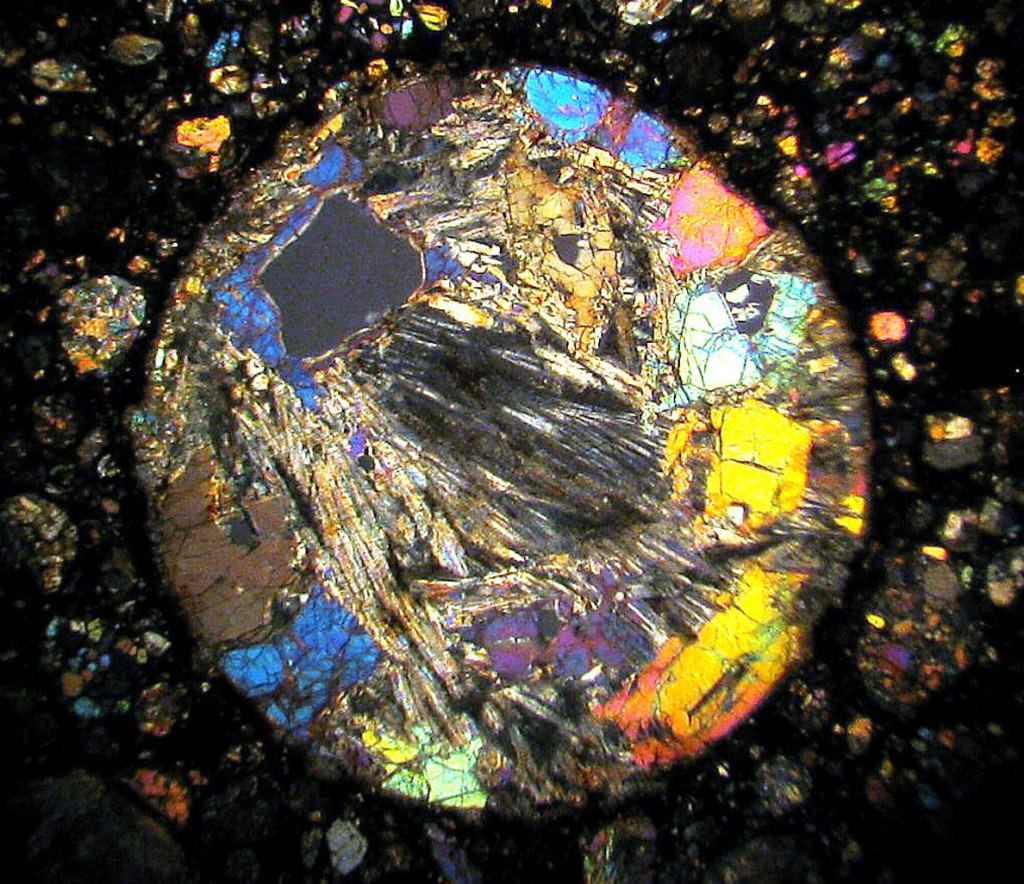

The evidence is in the form of a meteorite that crashed into Sudan’s Nubian Desert in 2008. The meteorite is known as 2008 TC3, or the Almahata Sitta meteorite. Inside the meteorite are tiny crystals called nanodiamonds that, according to this study, could only have formed in the high-pressure conditions within the growth of a planet. This contrasts previous thinking around these meteorites which suggests they formed as a result of powerful shockwaves created in collisions between parent bodies.

“We demonstrate that these large diamonds cannot be the result of a shock but rather of growth that has taken place within a planet.” – study co-author Philippe Gillet

Models of planetary formation show that terrestrial planets are formed by the accretion of smaller bodies into larger and larger bodies. Follow the process long enough, and you end up with planets like Earth. The smaller bodies that join together are typically between the size of the Moon and Mars. But evidence of these smaller bodies is hard to find.

One type of unique and rare meteorite, called a ureilite, could provide the evidence to back up the models, and that’s what fell to Earth in the Nubian Desert in 2008. Ureilites are thought to be the remnants of a lost planet that was formed in the first 10 million years of the Solar System, and then was destroyed in a collision.

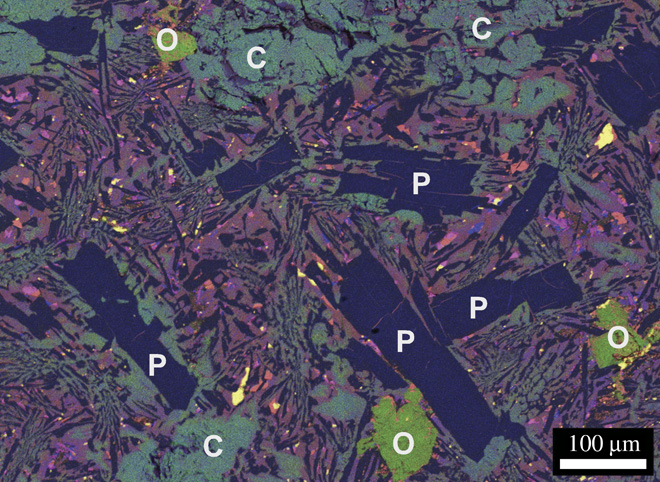

Ureilites are different than other stony meteorites. They have a higher component of carbon than other meteorites, mostly in the form of the aforementioned nanodiamonds. Researchers from Switzerland, France and Germany examined the diamonds inside 2008 TC3 and determined that they probably formed in a small proto-planet about 4.55 billion years ago.

Philippe Gillet, one of the study’s co-authors, had this to say in an interview with Associated Press: “We demonstrate that these large diamonds cannot be the result of a shock but rather of growth that has taken place within a planet.”

According to the research presented in this paper, these nanodiamonds were formed under pressures of 200,000 bar (2.9 million psi). This means the mystery parent-planet would have to have been as big as Mercury, or even Mars.

The key to the study is the size of the nanodiamonds. The team’s results show the presence of diamond crystals as large as 100 micrometers. Though the nanodiamonds have since been segmented by a process called graphitization, the team is confident that these larger crystals are there. And they could only have been formed by static high-pressure growth in the interior of a planet. A collision shock wave couldn’t have done it.

But the parent body of the ureilite meteorite in the study would have to have been subject to collisions, otherwise where is it? In the case of this meteorite, a collision and resulting shock wave still played a role.

The study goes on to say that a collision took place some time after the parent body’s formation. And this collision would have produced the shock wave that caused the graphitization of the nanodiamonds.

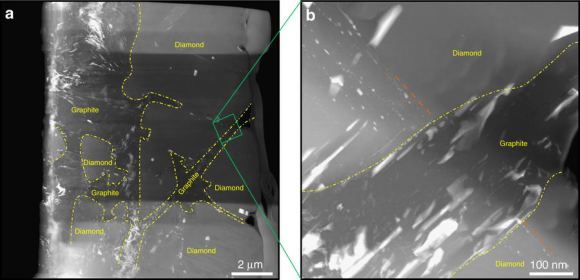

The key evidence is in what are called High-Angle Annular Dark-Field (HAADF) Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (STEM) images, as seen above. The image is two images in one, with the one on the right being a magnification of a part of the image on the left. On the left, dotted yellow lines indicate areas of diamond crystals separate from areas of graphite. On the right is a magnification of the green square.

The inclusion trails are what’s important here. On the right, the inclusion trails are highlighted with the orange lines. They clearly indicate inclusion lines that match between adjacent diamond segments. But the inclusion lines aren’t present in the intervening graphite. In the study, the researchers say this is “undeniable morphological evidence that the inclusions existed in diamond before these were broken into smaller pieces by graphitization.”

To summarize, this supports the idea that a small planet between the size of Mercury and Mars was formed in the first 10 million years of the Solar System. Inside that body, large nanodiamonds were formed by high-pressure growth. Eventually, that parent body was involved in a collision, which produced a shock wave. The shock wave then caused the graphitization of the nanodiamonds.

It’s an intriguing piece of evidence, and fits with what we know about the formation and evolution of our Solar System.

Sources:

![Distribution of new impact craters (yellow dots) discovered by analyzing 14,000 NAC temporal pairs. The two red dots mark the location of the 17 March 2013 and the 11 September 2013 impacts that were recorded by Earth-based video monitoring [NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University]](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Moon-new-crater-distribution-NASA-GSFC-ASU-1024x367.jpg)

![Example of a low reflectance (top) and high reflectance (bottom) splotch created either by a small impactor or more likely from secondary ejecta. In either case, the top few centimeters of the regolith (soil) was churned [NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University].](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Moon-craters-splotches-NASA.gif)