UPDATE: Tune in this Sunday as the good folks over at the Virtual Telescope Project feature a live webcast covering the Geminid meteor shower this Sunday on December 14th at 2:00 UT.

This weekend presents a good reason to brave the cold, as the Geminid meteor shower peaks on the morning of Sunday, December 14th. The Geminids are dependable, with a broad peak spanning several days, and would be as well known as their summer cousins the Perseids, were it not for the fact that they transpire in the dead of northern hemisphere winter.

But do not despair. While some meteor showers are so ephemeral as to be considered all but mythical in the minds of most meteor shower observers, the Geminids always deliver. We most recently caught a memorable display of the Geminids in 2012 from a dark sky locale in western North Carolina. Several meteors per minute pierced the Appalachian night, offering up one of the most memorable displays by this or any meteor shower in recent years.

The Geminids are worth courting frostbite for, that’s for sure. But there’s a curious history behind this shower and our understanding of meteor showers in general, one that demonstrates the refusal of some bodies in our solar system to “act right” and fit into neat scientific paradigms.

It wasn’t all that long ago that meteor showers — let alone meteorites — were not considered to be astronomical in origin at all. Indeed, the term meteor and meteorology have the same Greek root meaning “of the sky,” suggesting ideas of an atmospheric origin. Lightning, hail, meteors, you can kind of see how they got there.

In fact, you could actually face ridicule for suggesting that meteors had an extraterrestrial source back in the day. President Thomas Jefferson was said to have done just that concerning an opinion espoused by Benjamin Silliman of a December 14th, 1807, meteorite fall in Connecticut, leading to the apocryphal and politically-tinged response attributed to the president that, “I would more easily believe that two Yankee professors would lie, than that stones would fall from heaven.”

Indeed, no sooner than The French Academy of Sciences considered the matter settled earlier in the same decade, then a famous meteorite fall occurred in Normandy on April 26th, 1803,… right on their doorstep. The universe, it seemed, was thumbing its nose at scientific enlightenment.

Things really heated up with the spectacular display known as the Leonid meteor storm in 1833. On that November morning, stars seemed to fall like snowflakes from the sky. You can imagine the sight, as the Earth plowed headlong into the meteor stream. The visual effect of such a storm looks like the starship Enterprise plunging ahead at warp speed with stars streaming by, as if imploring humanity to get hip to the fact that meteor showers and their radiants are indeed a reality.

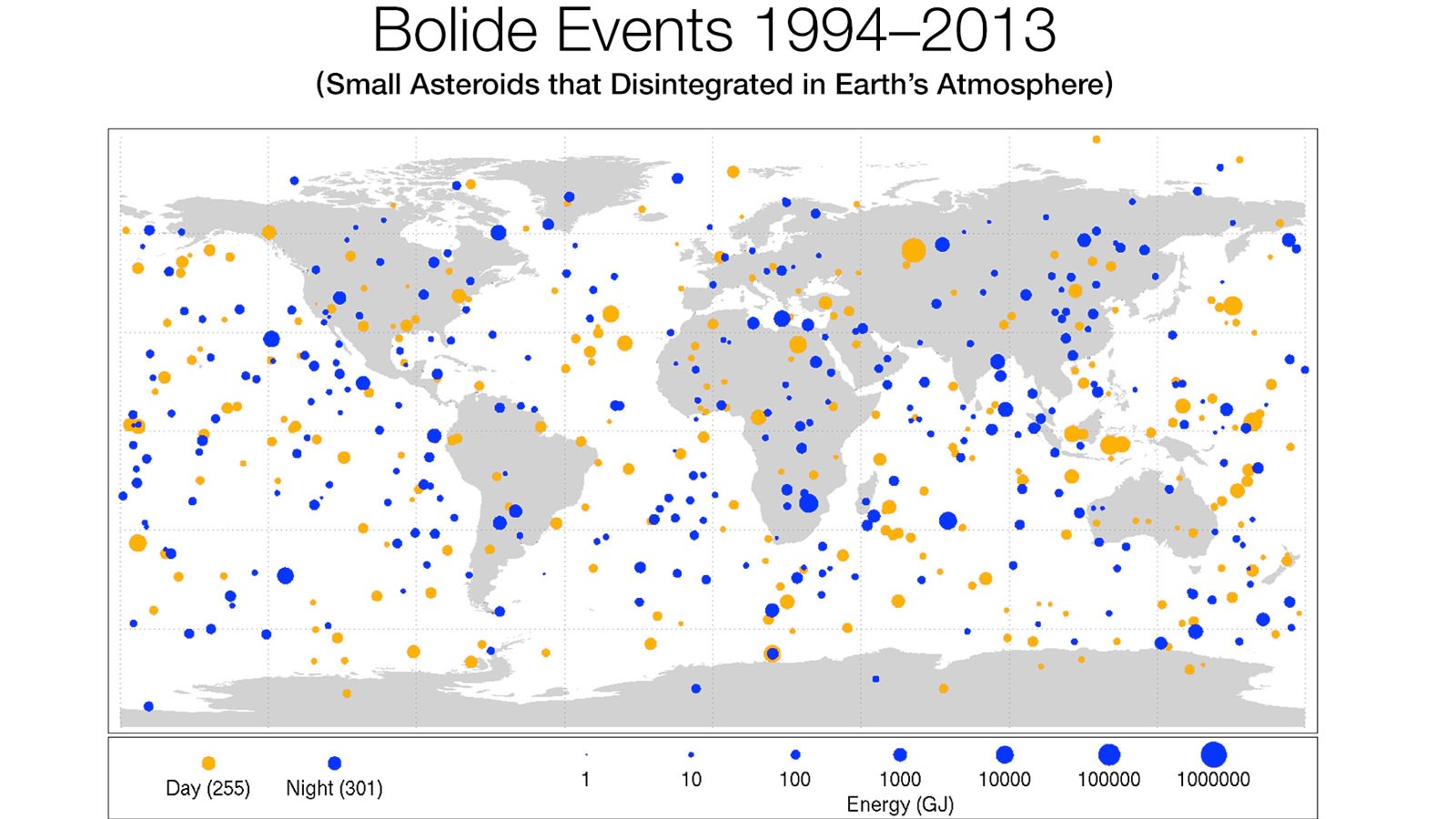

Still, a key problem persisted that gave ammunition to the naysayers: no new “space rocks” were found littering the ground at sunrise after a meteor shower. We now know that this is because meteor showers hail from wispy cometary debris left along intersections of the Earth’s orbit. Meteorite Man Geoff Notkin once mentioned to us that no meteorite fall has ever been linked to a meteor shower, though he does get lots of calls around Geminid season.

The name of the game in the 19th century soon became identifying new meteor showers. Streams evolve over time as they interact with planets (mostly Jupiter), and the 19th century played host to some epic meteor storms such as the Andromedids that have since been reduced to a trickle.

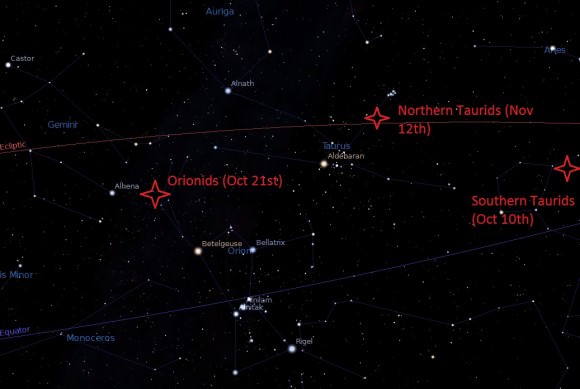

The Geminids are, however, the black sheep of the periodic meteor shower family. The shower was first noticed by US and UK observers in 1862, and by the 1870s astronomers realized that a new minor shower with a Zenithal Hourly Rate (ZHR) hovering around 15 was occurring near the middle of December from the constellation Gemini.

The source of the Geminids, however, was to remain a mystery right up until the late 20th century.

In the late 1940s, astronomer Fred Whipple completed the Harvard Meteor Project, which utilized a photographic survey that piqued the interest of astronomers worldwide: debris in the Geminid stream appeared to have an orbital period of just 1.65 years, coupled with a high orbital inclination. Modeling suggested that the parent body was most likely a short period comet, and that the stream had undergone repeated perturbations courtesy of Earth and Jupiter.

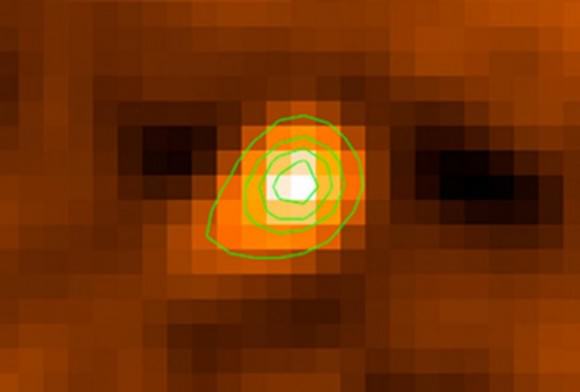

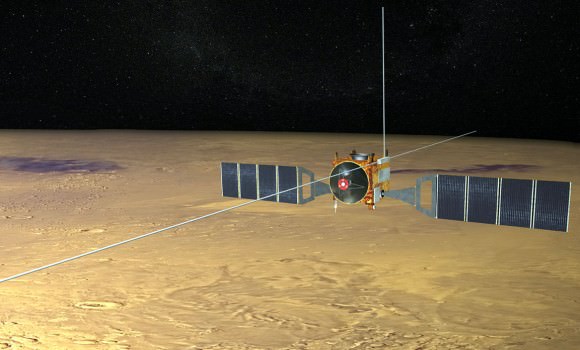

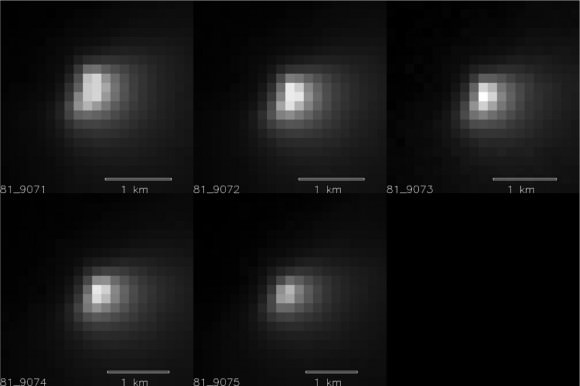

In 1983, the culprit was found, only to result in a deeper mystery. The Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS) discovered an asteroid fitting the bill crossing the constellation Draco. Backup observations from the Palomar observatory the next evening cinched the discovery, and today, we recognize the source of the Geminids as not a comet — as is the case with every other major meteor shower — but asteroid 3200 Phaethon, a 5 kilometre diameter rock in a 524 day orbit.

So why doesn’t this asteroid behave like one? Is 3200 Phaethon a rogue comet that has long since settled down for the quiet space rock life? Obviously, 3200 Phaethon has lots of material shedding off from its surface, as evidenced by the higher than normal ratio of fireballs seen during the Geminid meteors. 3200 Phaethon also passes 0.14 AUs from the Sun — 47% closer than Mercury — and has the closest perihelion of any known asteroid to the Sun, which bakes the asteroid periodically with every close pass.

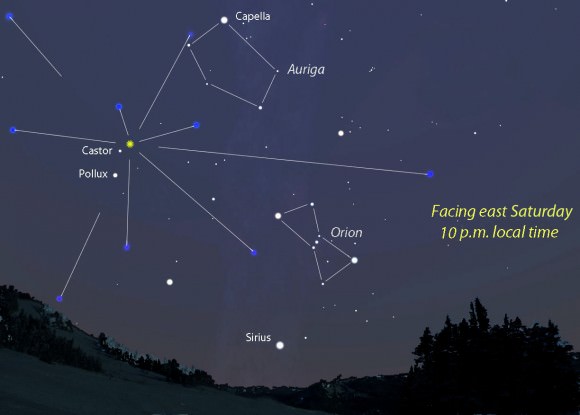

One thing is for certain: activity linked to the Geminid meteor stream is increasing. The Geminids actually surpassed the Perseids in terms of dependability and output since the 1960s, and have produced an annual peak ZHR of well over 100 in recent years. In 2014, expect a ZHR approaching 130 per hour as seen from a good dark sky site just after midnight local on the morning of December 14th as the radiant rides high in the sky. Remember, this shower has a broad peak, and it’s worth starting your vigil on Saturday or even Friday morning. The Geminid radiant also has a steep enough declination that local activity can start before midnight… also exceptional among meteor showers. This year, the 52% illuminated Moon rises around midnight local on the morning of December 14th.

And there’s another reason to keep an eye on the 2014 Geminids. 3200 Phaethon passed 0.12 AU (18 million kilometers) from Earth on December 10th, 2007, which boosted displays in the years after. And just three years from now, the asteroid will pass even closer on December 10th, 2017, at just 0.07 AUs (10.3 million kilometers) from Earth…

Are we due for some enhanced activity from the Geminids in the coming years?

All good reasons to bundle up and watch for the “Tears of the Twins” this coming weekend, and wonder at the bizzaro nature of the shower’s progenitor.