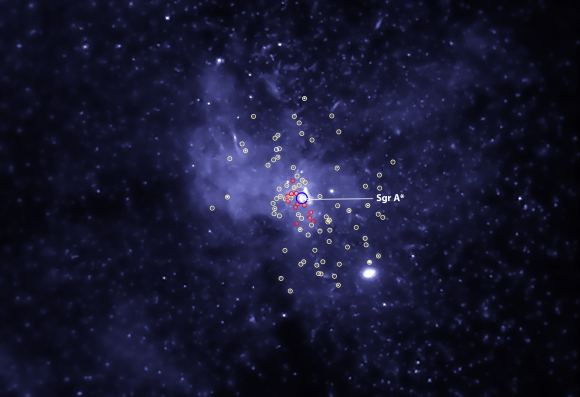

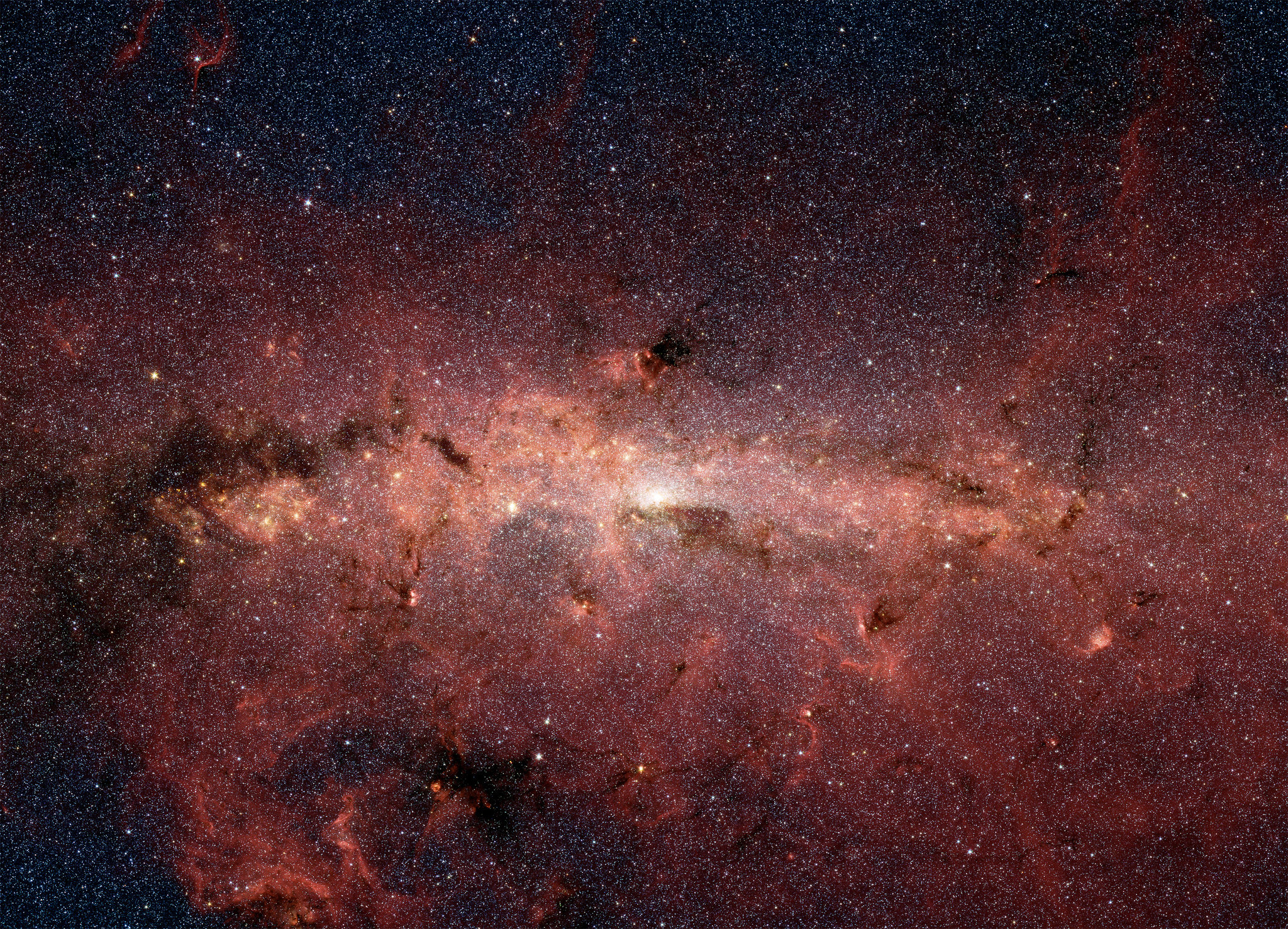

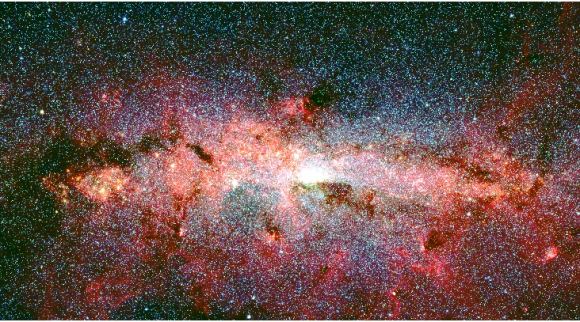

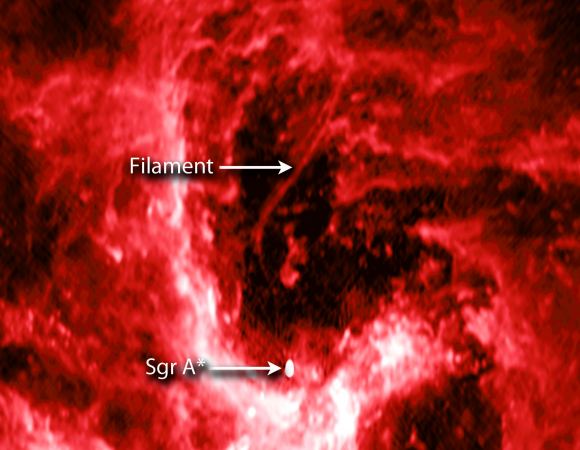

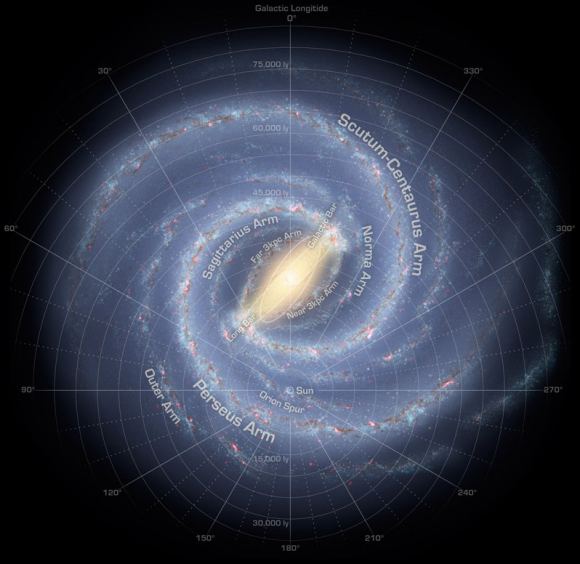

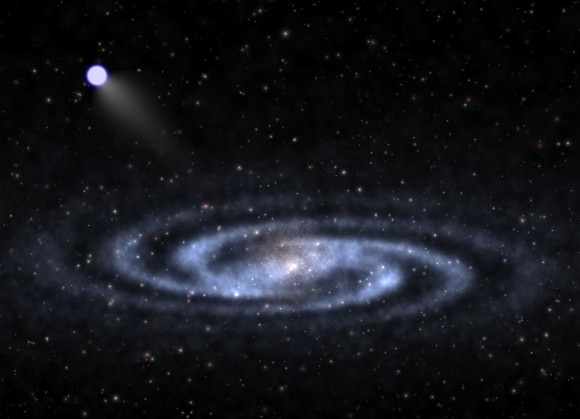

During the 1970s, astronomer became aware of a massive radio source at the center of our galaxy that they later realized was a Supermassive Black Hole (SMBH) – which has since been named Sagittarius A*. And in a recent survey conducted by NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, astronomers discovered evidence for hundreds or even thousands of black holes located in the same vicinity of the Milky Way.

But, as it turns out, the center of our galaxy has more mysteries that are just waiting to be discovered. For instance, a team of astronomers recently detected a number of “mystery objects” that appeared to be moving around the SMBH at Galactic Center. Using 12 years of data taken from the W.M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii, the astronomers found objects that looked like dust clouds but behaved like stars.

The research was conducted through a collaboration between Randy Campbell at the W.M. Keck Observatory, members of the Galactic Center Group at UCLA (Anna Ciurlo, Mark Morris, and Andrea Ghez) and Rainer Schoedel of the Instituto de Astrofisica de Andalucia (CSIC) in Granada, Spain. The results of this study were presented at the 232nd American Astronomical Society Meeting during a press conference titled “The Milky Way & Active Galactic Nuclei”.

As Ciurlo explained in a recent W.M. Keck press release:

“These compact dusty stellar objects move extremely fast and close to our Galaxy’s supermassive black hole. It is fascinating to watch them move from year to year. How did they get there? And what will they become? They must have an interesting story to tell.”

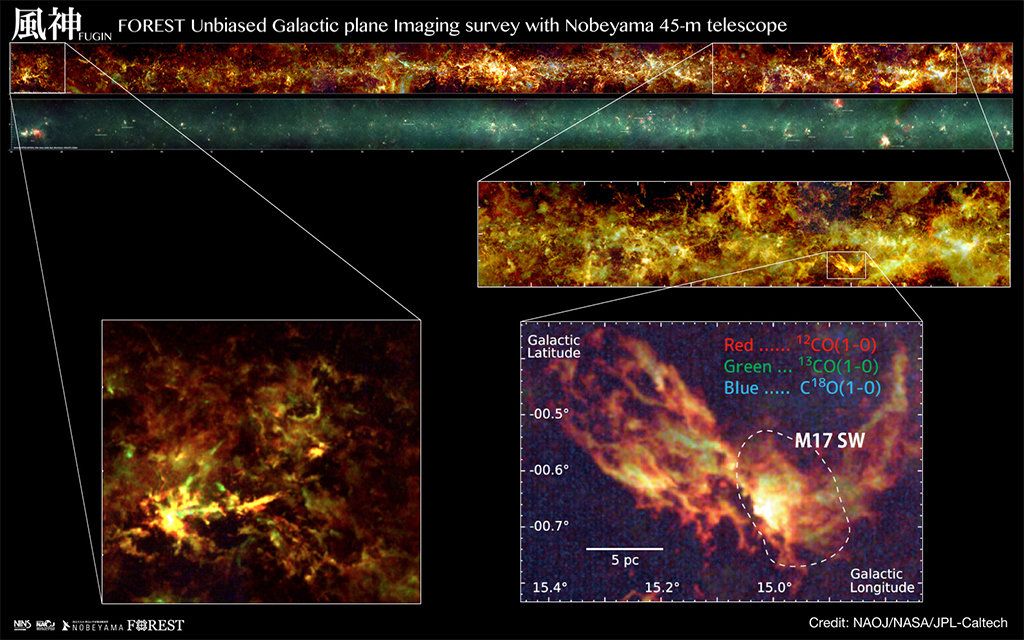

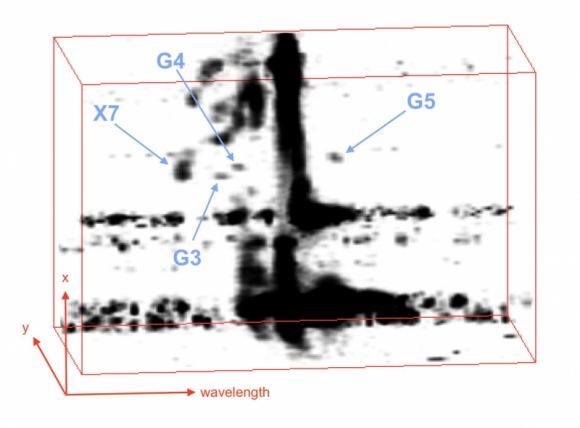

The researchers made their discovery using 12 years of spectroscopic measurements obtained by the Keck Observatory’s OH-Suppressing Infrared Imaging Spectrograph (OSIRIS). These objects – which were designed as G3, G4, and G5 – were found while examining the gas dynamics of the center of our galaxy, and were distinguished from background emissions because of their movements.

“We started this project thinking that if we looked carefully at the complicated structure of gas and dust near the supermassive black hole, we might detect some subtle changes to the shape and velocity,” explained Randy Campbell. “It was quite surprising to detect several objects that have very distinct movement and characteristics that place them in the G-object class, or dusty stellar objects.”

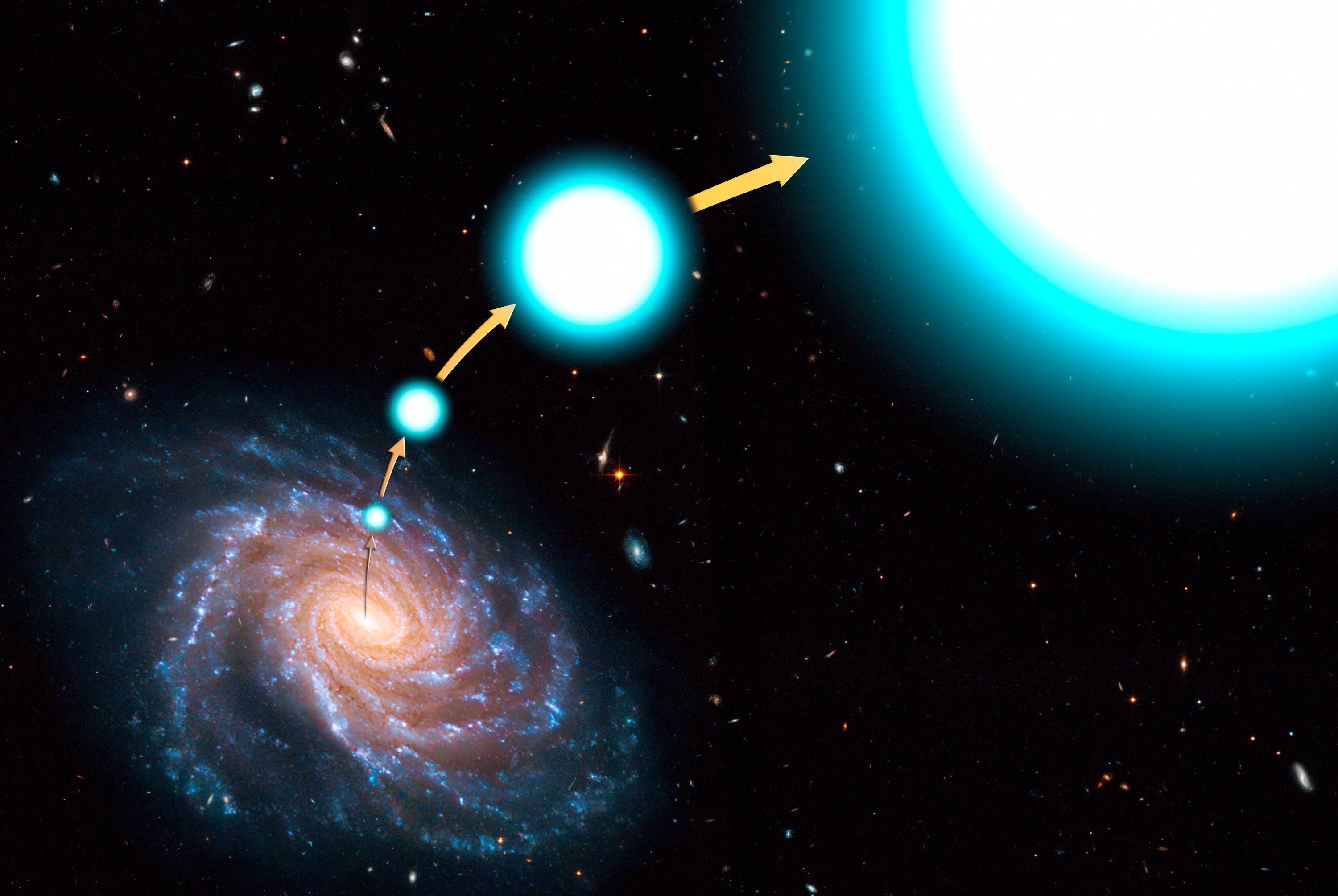

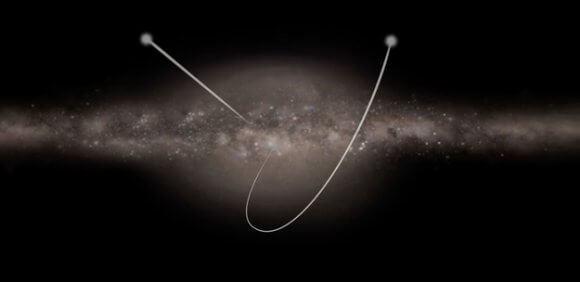

Astronomers first discovered G-objects in proximity to Sagittarius A* more than a decade ago – G1 was discovered in 2004 and G2 in 2012. Initially, both were thought to be gas clouds until they made their closest approach to the supermassive black hole and survived. Ordinarily, the SMBHs gravitational pull would shred gas clouds apart, but this did not happen with G1 and G2.

Because these newly discovered infrared sources (G3, G4, and G5) shared the physical characteristics of G1 and G2, the team concluded that they could potentially be G-objects. What makes G-objects unusual is their “puffiness”, where they appear to be cloaked in a layer of dust and gas that makes them difficult to detect. Unlike other stars, astronomers only see a glowing envelope of dust when looking at G-objects.

To see these objects clearly through their obscuring envelope of dust and gas, Campbell developed a tool called the OSIRIS-Volume Display (OsrsVol). As Campbell described it:

“OsrsVol allowed us to isolate these G-objects from the background emission and analyze the spectral data in three dimensions: two spatial dimensions, and the wavelength dimension that provides velocity information. Once we were able to distinguish the objects in a 3-D data cube, we could then track their motion over time relative to the black hole.”

UCLA Astronomy Professor Mark Morris, a co-principal investigator and fellow member of UCLA’s Galactic Center Orbits Initiative (GCOI), was also involved in the study. As he indicated:

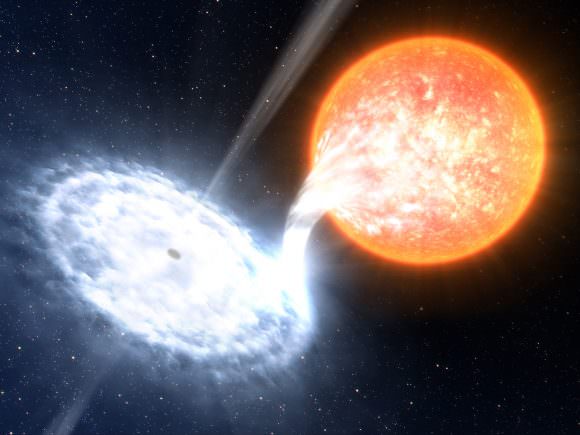

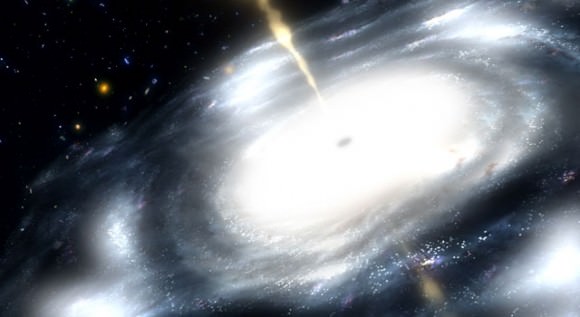

“If they were gas clouds, G1 and G2 would not have been able to stay intact. Our view of the G-objects is that they are bloated stars – stars that have become so large that the tidal forces exerted by the central black hole can pull matter off of their stellar atmospheres when the stars get close enough, but have a stellar core with enough mass to remain intact. The question is then, why are they so large?

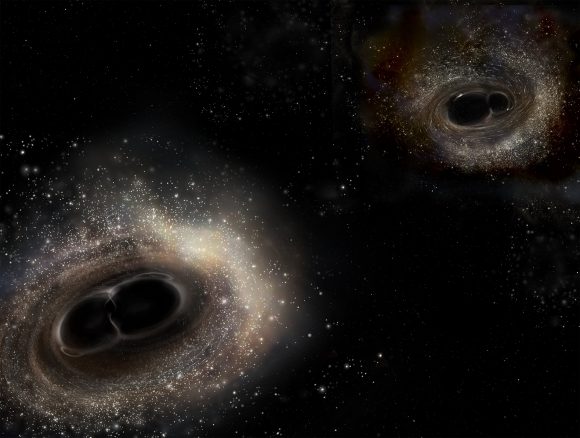

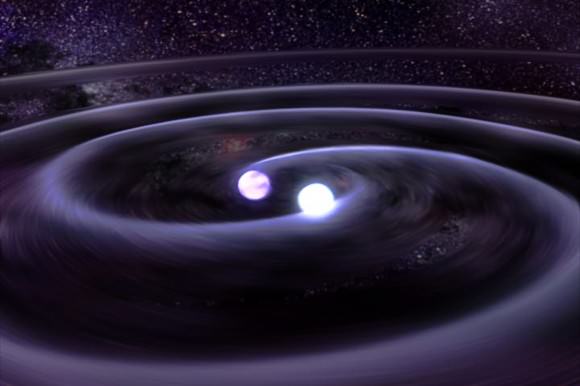

After examining the objects, the team noticed that there was a great deal of energy was emanating from them, more than what would be expected from typical stars. As a result, they theorized that these G-objects are the result of stellar mergers, which occur when two stars that orbit each other (aka. binaries) crash into each other. This would have been caused by the long-term gravitational influence of the SMBH.

The resulting single object would be distended (i.e. swell up) over the course of millions of years before it finally settled down and appeared like a normal-sized star. The combined objects that resulted from these violent mergers could explain where the excess energy came from and why they behave like stars do. As Andrea Ghez, the founder and director of GCOI, explained:

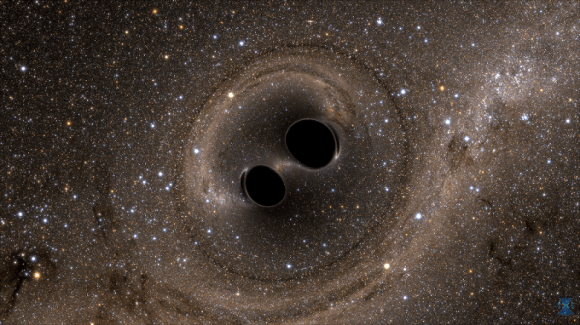

“This is what I find most exciting. If these objects are indeed binary star systems that have been driven to merge through their interaction with the central supermassive black hole, this may provide us with insight into a process which may be responsible for the recently discovered stellar mass black hole mergers that have been detected through gravitational waves.”

Looking ahead, the team plans to continue following the size and shape of the G-objects’ orbits in the hopes of determining how they formed. They will be paying especially close attention when these stellar objects make their closest approach to Sagittarius A*, since this will allow them to further observe their behavior and see if they remain intact (as G1 and G2 did).

This will take a few decades, with G3 making its closest pass in 20 years and G4 and G5 taking decades longer. In the meantime, the team hopes to learn more about these “puffy” star-like objects by following their dynamical evolution using Keck’s OSIRIS instrument. As Ciurlo stated:

“Understanding G-objects can teach us a lot about the Galactic Center’s fascinating and still mysterious environment. There are so many things going on that every localized process can help explain how this extreme, exotic environment works.”

And be sure to check out this video of the presentation, which takes place from 18:30 until 30:20:

Further Reading: Keck Observatory