About 70 pages into The Milky Way, An Insider’s Guide, a strange craving for hamburgers overtook me.

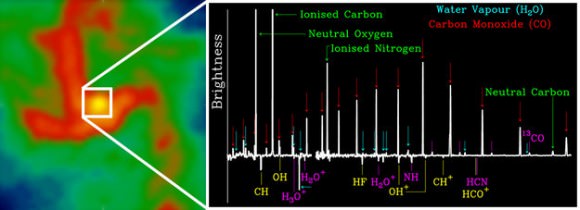

The text of William H. Waller, an astronomer and author, was in the midst of a discussion of a kind of organic molecule called PAHs, or polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. As I was reading about the Spitzer Space Telescope’s discoveries in this field, the last sentence in the paragraph struck me:

“On Earth, PAHs are as familiar to us as the mouth-watering aromas of a barbecued hamburger, the sweetly acrid odors of burning tobacco, and the choking fumes behind a diesel bus,” Waller wrote. “If we had big enough nostrils, what would our home galaxy smell like?”

I’m never going to read about PAHs again without wanting to run to that greasy joint nearby my place. Or, I guess, run in the opposite direction from the nearest bus stop.

Waller’s book is designed as a reference guide for those with a serious interest in astronomy, but who perhaps are just starting to think about taking it in school. Another audience could be the serious amateur astronomer wanting to understand more about telescopic targets.

While not light cottage reading, Waller isn’t afraid to throw in references to popular culture or to drop in humor now and then, much like a kindly Astronomy 101 professor trying to snap your attention back when it might be wandering.

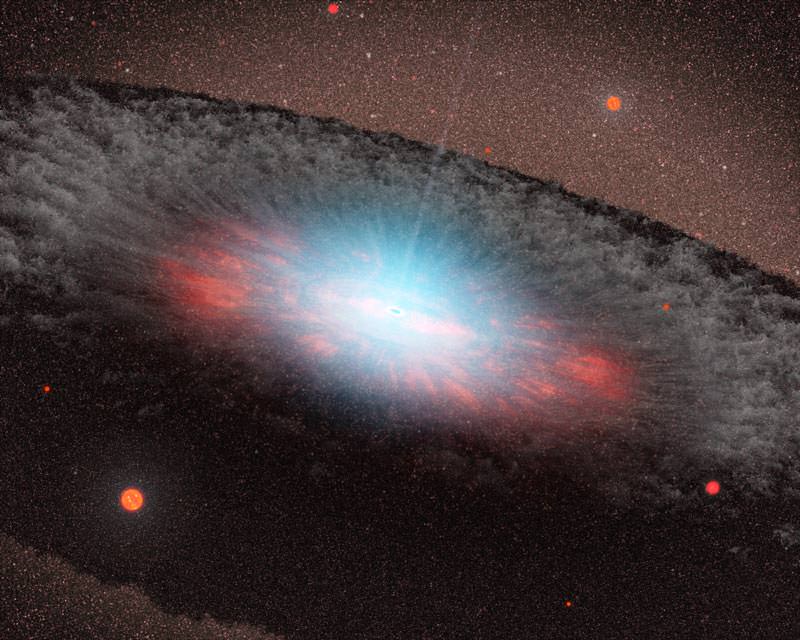

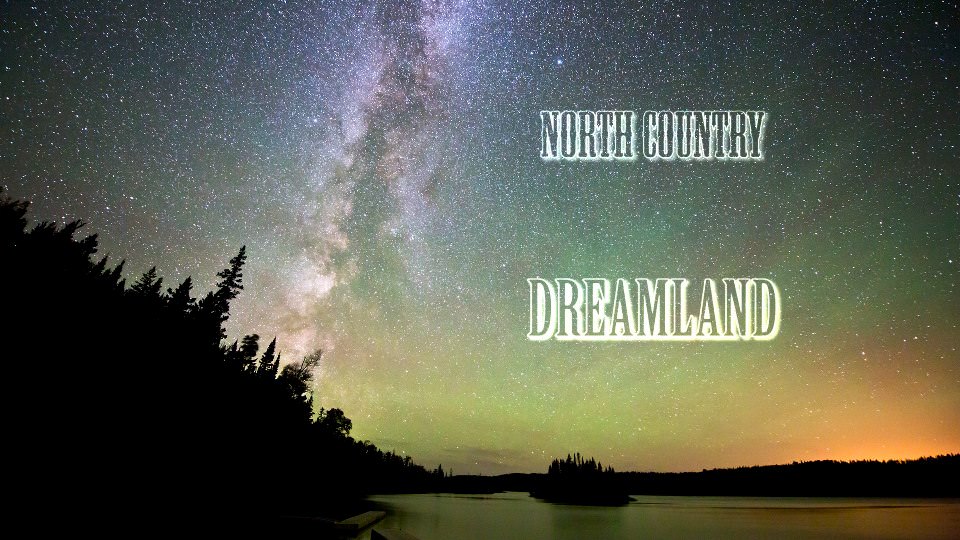

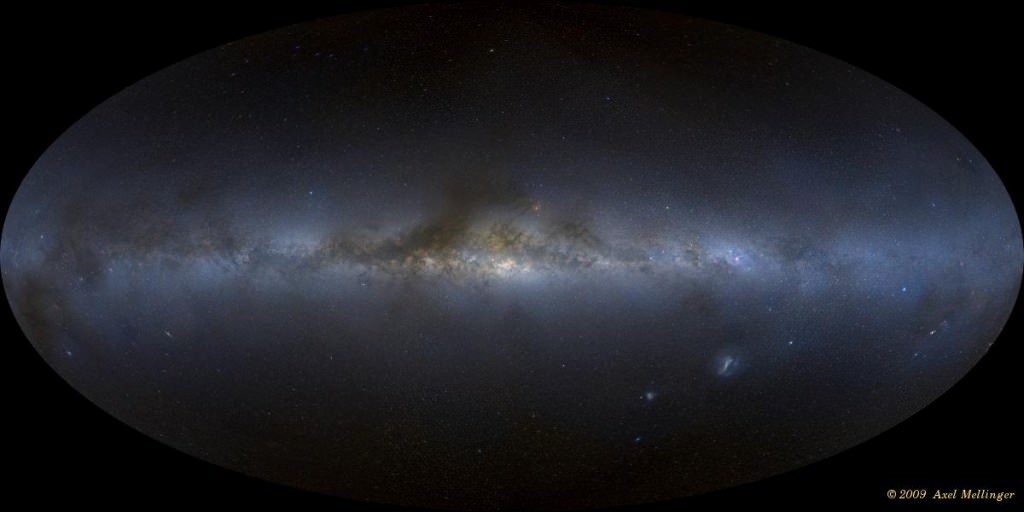

On that note, this illustration in the book (with some important context) may be my favorite astronomy textbook image of all time. It’s another example of how science can, kinda sorta, meet science fiction.

The breadth of material Waller covers is astonishing. One 43-page chapter is essentially a history of how we looked at the sky mythologically, philosophically and of course scientifically — a feat that is more interesting when you realize a goodly number of those pages are actually in-context, interesting illustrations.

The book’s bulk, though, looks to summarize astronomical phenomena. It’s definitely not for the beginning reader; for example, the term “nebula” is referred to several times before finally being defined some pages into the book. But if you know what Waller is aiming at, you’ll learn quite a bit.

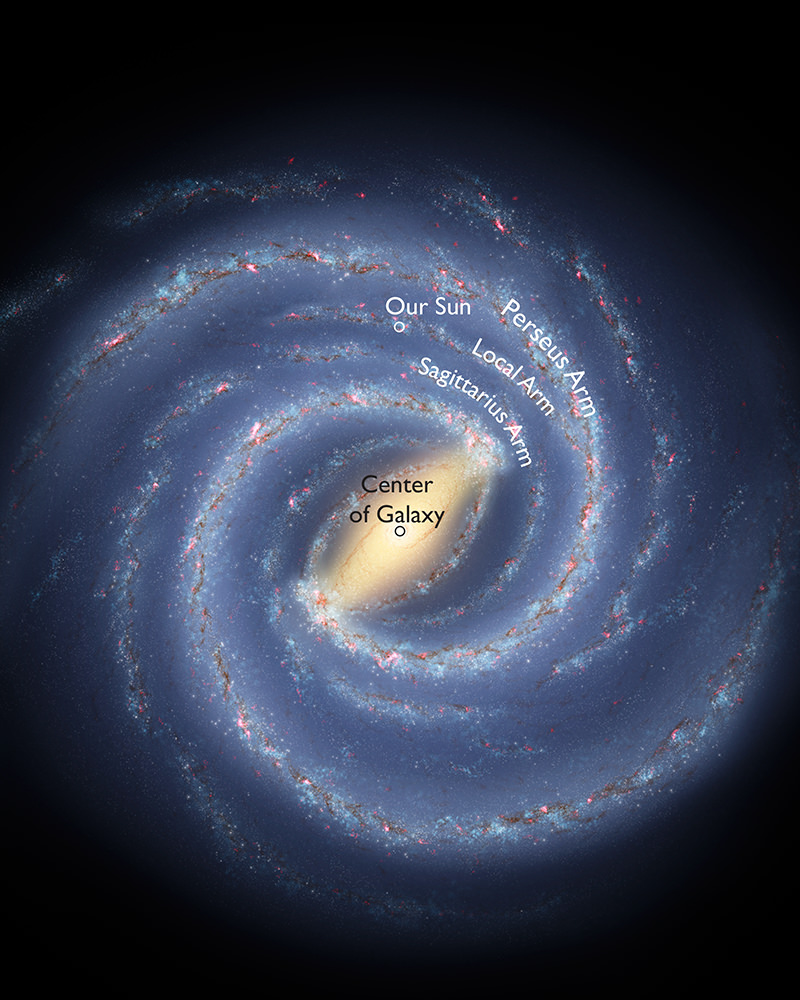

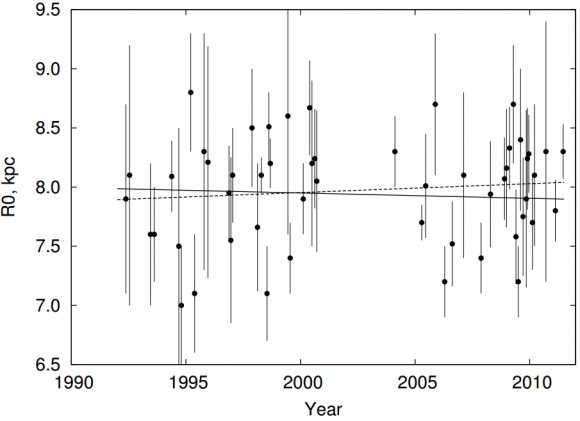

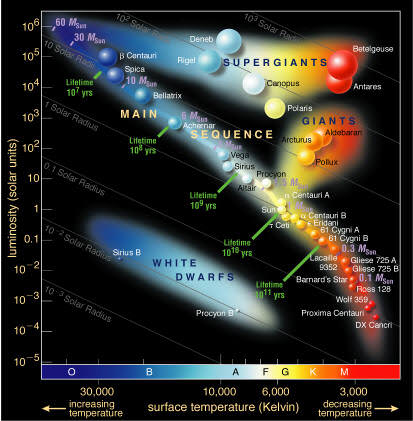

The book purports to be about galaxies, but much of it is also devoted to what I think of as hacking the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram showing the types of stars in relation to each other.

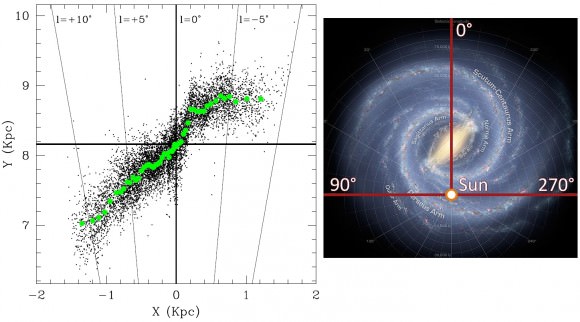

Three full chapters are devoted to star birth, the lives of stars and stellar afterlives (y’know, supernovae and the like.) This makes perfect sense as galaxies are collections of stars, so it is only by studying these individual members that we can truly appreciate what a galaxy is about.

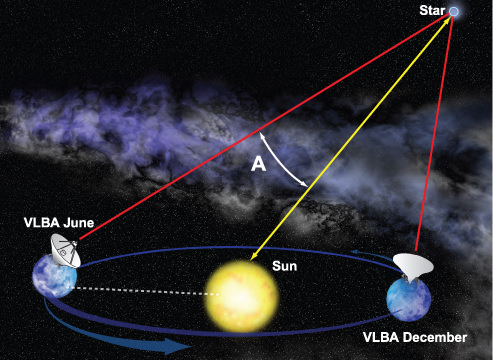

The more serious reader will be pleased to see equations included (such as calculating parallax) and a detailed explanation of Drake’s Equation showing the factors behind the probability of finding extraterrestrial life.

So to sum up: definitely not for the person with a nascent interest in astronomy, but a valuable reference for those looking to learn about it seriously. As a space journalist, I’ll definitely keep this book on my shelf.