[/caption]

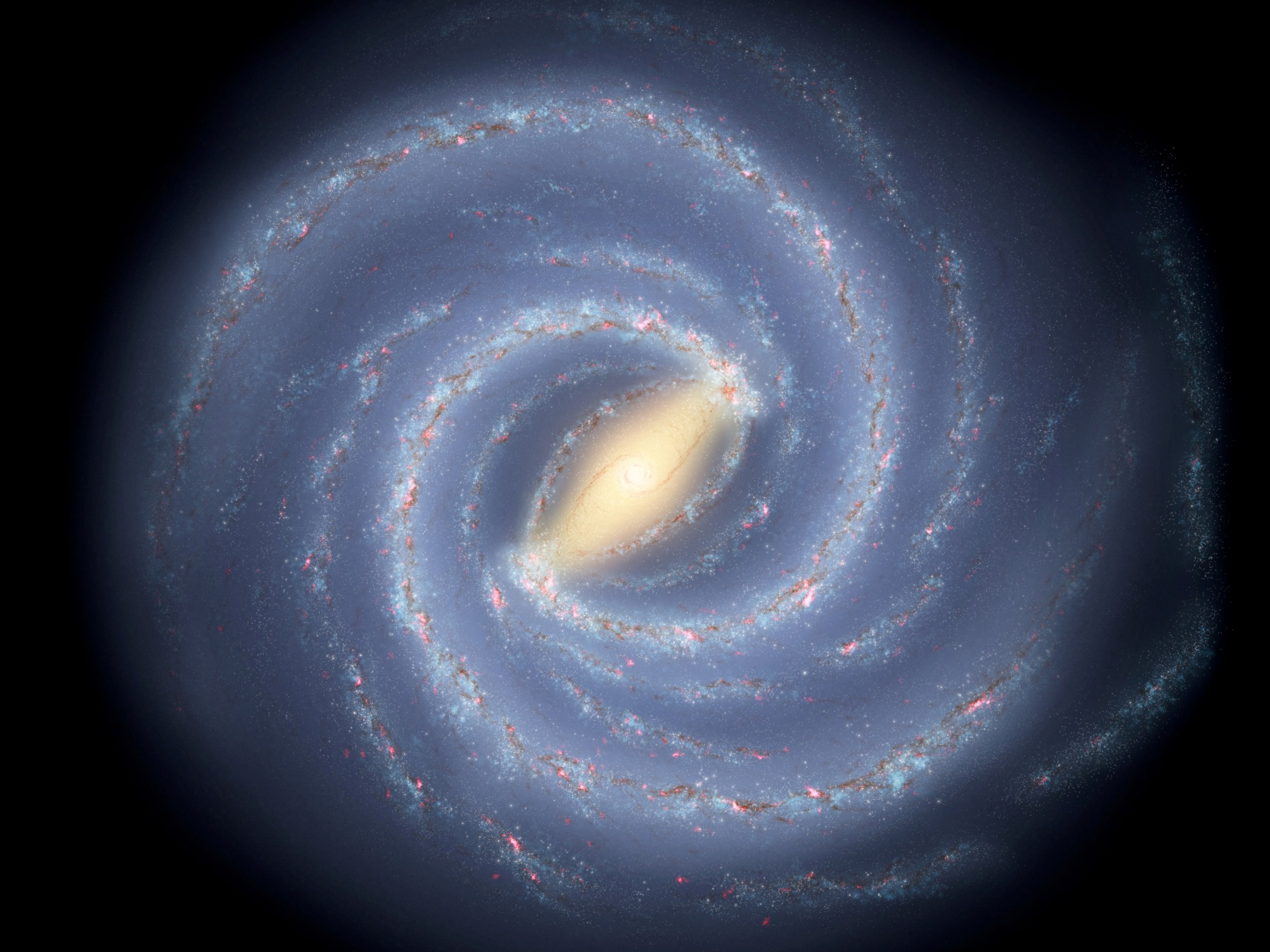

On Friday, I wrote about the population of the thick disk and how surveys are revealing that this portion of our galaxy is largely made of stars stolen from cannibalized dwarf galaxies. This fits in well with many other pieces of evidence to build up the general picture of galactic formation that suggests galaxies form through the combination of many small additions as opposed to a single, gigantic collapse. While many streams of what is, presumably, tidally shredded galaxies span the outskirts of the Milky Way, and other objects exist that are still fully formed galaxies, few objects have yet been identified as a satellite that is undergoing the process of tidal disruption.

A new study, to be published in the October issue of the Astrophysical Journal suggests that the Hercules satellite galaxy may be one of the first of this intermediary forms discovered.

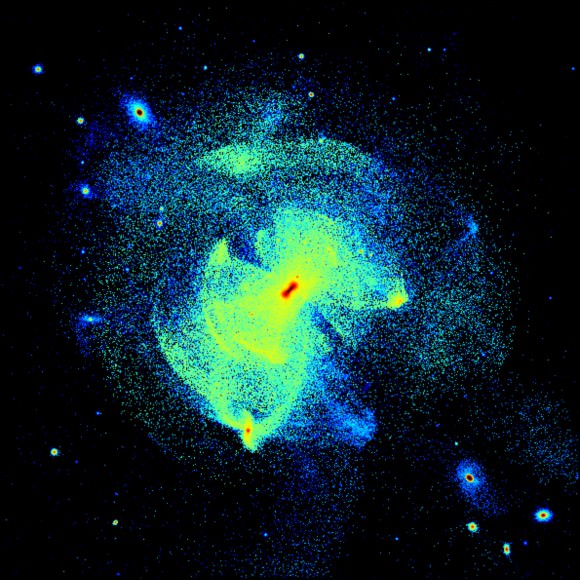

In the past decade, numerous minor stellar systems have been discovered in the halo of our Milky Way galaxy. The properties of these systems have suggested to astronomers that they are faint galaxies in their own right. Although many have elongated and elliptical shapes (averaging an ellipticity of 0.47; 0.15 higher than that of brighter dwarf galaxies that orbit further out), simulations have suggested that even these stretched dwarfs are still able to remain largely cohesive. In general, the galaxy will remain intact until it is stretched to an ellipticity of 0.7. At this point, a minor galaxy will lose ~90% of its member stars and dissolve into a stellar stream.

In 2008, Munoz et al. reported the first Milky Way satellite that was clearly over this limit. The Ursa Major I satellite was shown to have an ellipticity of 0.8. Munoz suggested that this, as well as the Hercules and Ursa Major II dwarfs were undergoing tidal break up.

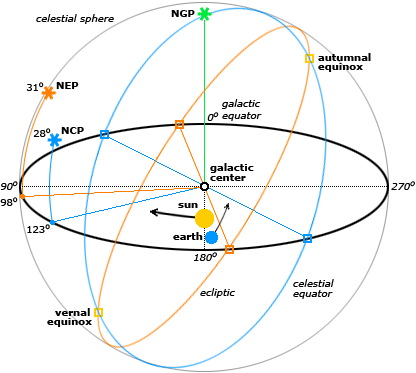

The new paper, by Nicolas Martin and Shoko Jin, further analyzes this proposition for the Hercules satellite by going further and examining the orbital characteristics to ensure that their passage would continue to distort the galaxy sufficiently. The system already contains an ellipticity of 0.68, which puts it just under the theoretical limit.

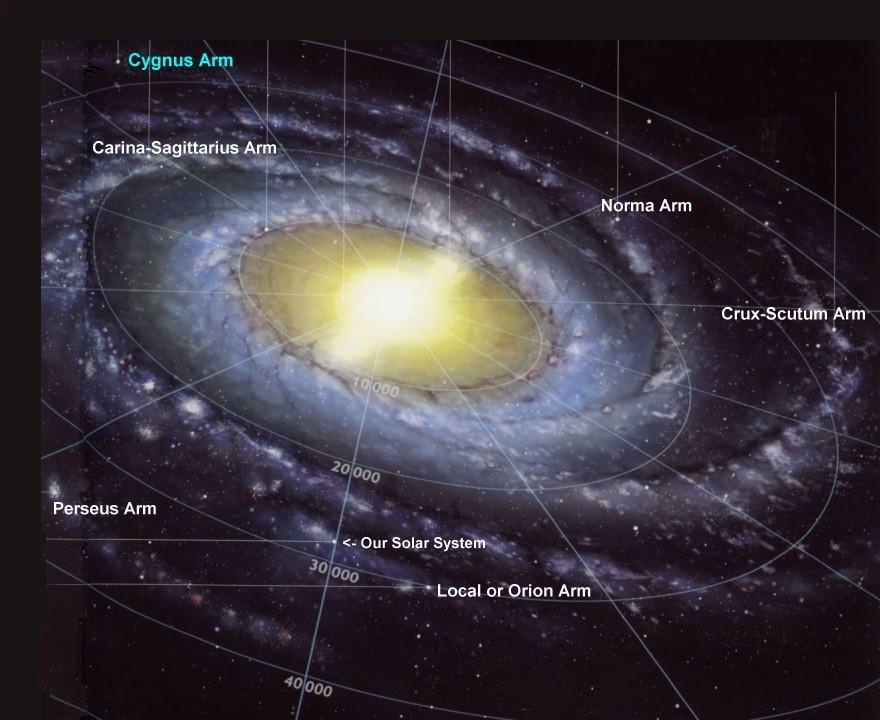

The team looked to see just how closely the satellite would pass to our own galactic center. The closer it passed, the more disruption it would feel. By projecting the orbit, they estimated the galaxy would come within ~6 kiloparsecs of the galactic center which is about 40% of the radius of the galaxy overall. While this may not seem especially close Martin and Jin report that they cannot conclude that it will be insufficient. They state that disruption would be dependent on “the properties of the stellar system at that time of its journey in the Milky Way potential and, as such, out of reach to the current observer.”

However, there were some telling signs that the dwarf may already be shedding stars. Along the major axis of the galaxy, deep imaging has revealed a smaller number of stars that does not appear to be bound to the galaxy itself. Photometry of these stars has shown that their distribution on a color-magnitude diagram is strikingly similar to that of the Hercules galaxy itself.

At this point, we cannot fully determine if the Hercules galaxy is doomed to become another stellar stream around the Milky Way, but if it is not truly in the process of breaking up, it seems to be on the very edge.