[/caption]

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is the much anticipated, long awaited “next generation” telescope, which we hope will look further back in time, and deeper within dusty star forming regions, using longer wavelengths and more sensitivity than any previous space telescope. In order to take us to this next level, you’d kinda figure that new technologies would have to be developed in order for this ground-breaking, super-huge telescope to be built. You’d be right.

In fact, engineers had to use a little unobtainium to build the one-of-a-kind chassis, the backbone that will hold the spacecraft together.

Unobtainium isn’t just the name of the material mined in James Cameron’s movie “Avatar.” It is a word used in engineering — and sometimes fiction – to describe any extremely rare, costly, or physically impossible material or device needed to fulfill a given design for a given application.

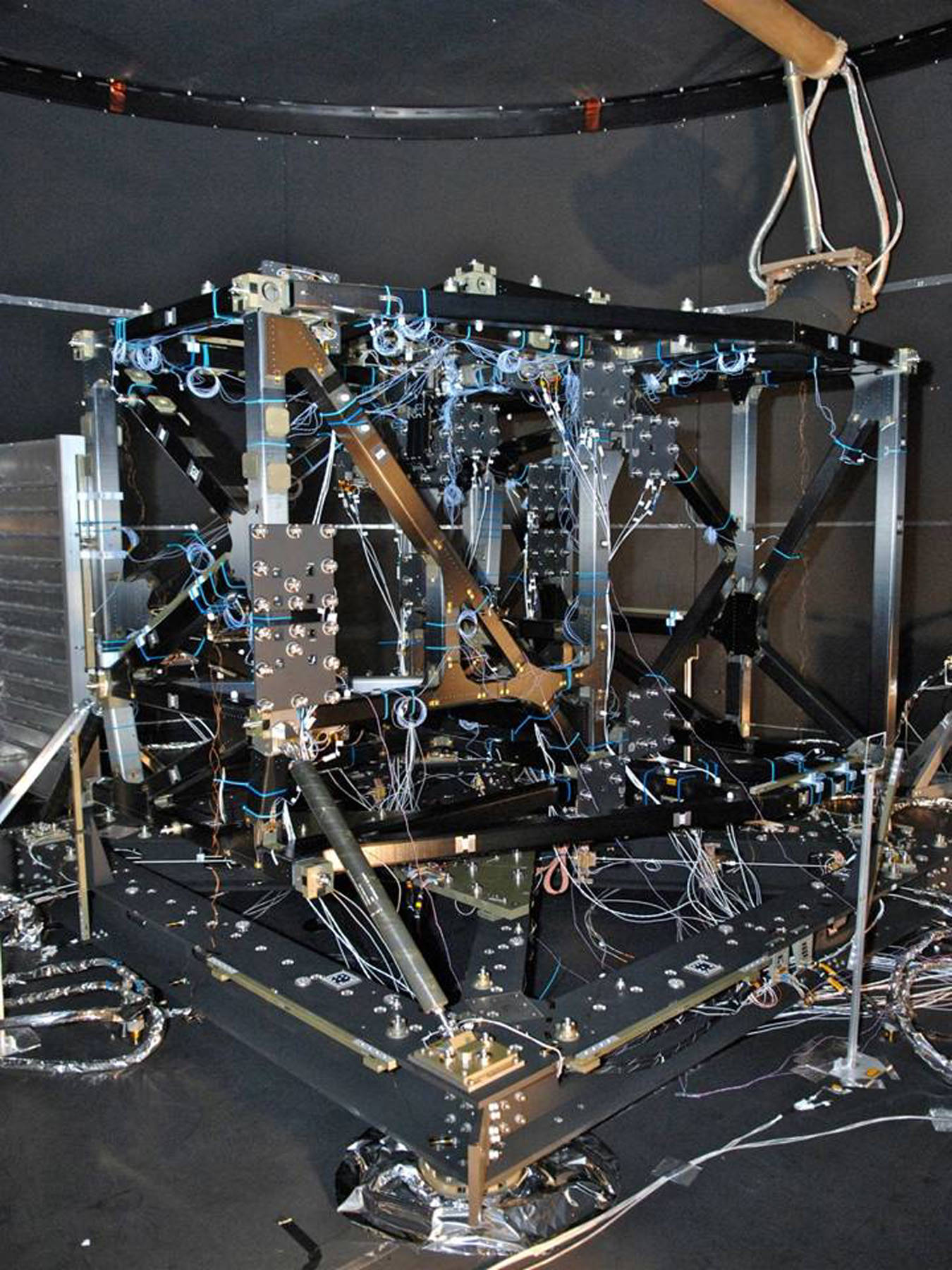

The chassis for JWST – called the the Integrated Science Instrument Module ISIM – is made of a never-before-manufactured composite material which had to withstand the super-cold temperatures it will encounter when the observatory reaches its orbit 1.5-million kilometers (930,000 miles) from Earth.

The ISIM just passed an extremely important test, surviving temperatures that plunged as low as 27 Kelvin (-411 degrees Fahrenheit), colder than the surface of Pluto during a cycle of testing in Goddard’s Space Environment Simulator — a three-story thermal-vacuum chamber that simulates the temperature and vacuum conditions found in space.

The team at Goddard Space Flight Center who were charged with building the chassis needed a material that would assure the various instruments on JWST would maintain a precise cryogenic alignment and stability, yet survive the extreme gravitational forces experienced during launch.

The test was done to find out whether the car-sized structure contracted and distorted as predicted when it cooled from room temperature to the frigid — very important since the science instruments must maintain a specific location on the structure to receive light gathered by the telescope’s 6.5-meter (21.3-feet) primary mirror. If the structure shrunk or distorted in an unpredictable way due to the cold, the instruments no longer would be in position to gather data about everything from the first luminous glows following the Big Bang to the formation of star systems capable of supporting life.

When they first began, there was nothing out there that remotely fit the description of what was needed. So, that left one alternative: developing their own as-yet-to-be manufactured material, which team members jokingly referred to as “unobtainium.” Through mathematical modeling, the team discovered that by combining two composite materials, it could create a carbon fiber/cyanate-ester resin system that would be ideal for fabricating the structure’s square tubes that measure 75-mm (3-inch) in diameter.

During the recent 26-day test, and with repeated cycles of testing, the truss-like assembly designed by Goddard engineers did not crack. The structure shrunk as predicted by only 170 microns — the width of a needle —when it reached 27 Kelvin (-411 degrees Fahrenheit), far exceeding the design requirement of about 500 microns. “We certainly wouldn’t have been able to realign the instruments on orbit if the structure moved too much,” said ISIM Structure Project Manager Eric Johnson. “That’s why we needed to make sure we had designed the right structure.”

This type of structure could serve NASA in the future for the next-generation beyond JWST, and could also be a “spinoff” that manufacturers could find useful in designing structures that demand a high tolerance in conditions.

Source: NASA Goddard