NASA’s Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2) at the Launch Pad

This black-and-white infrared view shows the launch gantry, surrounding the United Launch Alliance Delta II rocket with the Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2) satellite onboard. The photo was taken at Space Launch Complex 2, Friday, June 27, 2014, Vandenberg Air Force Base, Calif. OCO-2 is set for a July 1, 2014 launch. Credit: NASA/Bill Ingalls[/caption]

After a lengthy hiatus, the workhorse Delta II rocket that first launched a quarter of a century ago and placed numerous renowned NASA science missions into Earth orbit and interplanetary space, as well as lofting dozens of commercial and DOD missions, is about to soar again this week on July 1 with NASA’s Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2) sniffer to study atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2).

OCO-2 is NASA’s first mission dedicated to studying atmospheric carbon dioxide, the leading human-produced greenhouse gas and the principal human-produced driver of climate change.

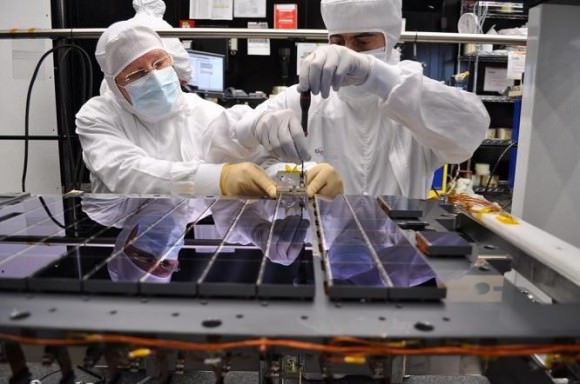

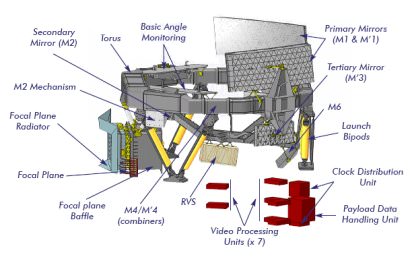

The 999 pound (454 kilogram) observatory is equipped with one science instrument consisting of three high-resolution, near-infrared spectrometers fed by a common telescope. It will collect global measurements of atmospheric CO2 to provide scientists with a better idea of how CO2 impacts climate change.

The $467.7 million OCO-2 mission is set to blastoff atop the United Launch Alliance (ULA) Delta II rocket on Tuesday, July 1 from Space Launch Complex 2 at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California.

Liftoff is slated for 5:56 a.m. EDT (2:56 a.m. PDT) at the opening of a short 30-second launch window.

NASA TV will broadcast the launch live with countdown commentary beginning at 3:45 a.m. EDT (12:45 a.m. PDT): http://www.nasa.gov/multimedia/nasatv/

The California weather prognosis is currently outstanding at 100 percent ‘GO’ for favorable weather conditions at launch time.

The two stage Delta II 7320-10 launch vehicle is 8 ft in diameter and approximately 128 ft tall. It is equipped with a trio of strap on solid rocket motors. This marks the 152nd Delta II launch overall and the 51st for NASA since 1989.

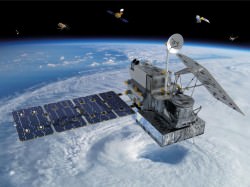

The last time a Delta II rocket flew was nearly three years ago in October 2011 from Vandenberg for the Suomi National Polar-Orbiting Partnership (NPP) weather satellite.

The final Delta II launch from Cape Canaveral on Sept. 10, 2011 boosted NASA’s twin GRAIL gravity mapping probes to the Moon.

The Delta II will boost OCO-2 into a 438-mile (705-kilometer) altitude, near-polar orbit. Spacecraft separation from the rocket occurs 56 minutes 15 seconds after launch.

It will lead a constellation of five other international Earth monitoring satellites that circle Earth.

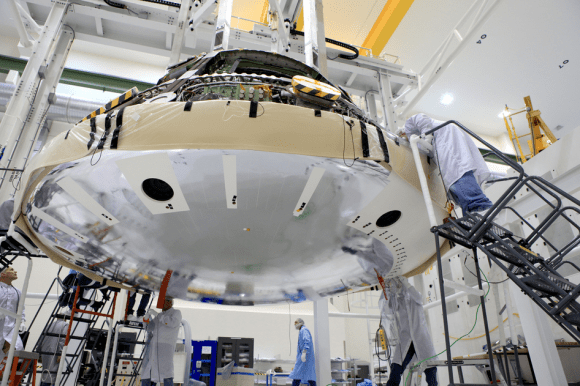

The phone-booth sized OCO-2 was built by Orbital Sciences and is a replacement for the original OCO which was destroyed during the failed launch of a Taurus XL rocket from Vandenberg back in February 2009 when the payload fairing failed to open properly.

OCO-2 is the second of NASA’s five new Earth science missions launching in 2014 and is designed to operate for at least two years during its primary mission. It follows the successful blastoff of the joint NASA/JAXA Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) Core Observatory satellite on Feb 27.

Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2) mission will provide a global picture of the human and natural sources of carbon dioxide, as well as their “sinks,” the natural ocean and land processes by which carbon dioxide is pulled out of Earth’s atmosphere and stored, according to NASA..

“Carbon dioxide in the atmosphere plays a critical role in our planet’s energy balance and is a key factor in understanding how our climate is changing,” said Michael Freilich, director of NASA’s Earth Science Division in Washington.

“With the OCO-2 mission, NASA will be contributing an important new source of global observations to the scientific challenge of better understanding our Earth and its future.”

It will record around 100,000 CO2 measurements around the world every day and help determine its source and fate in an effort to understand how human activities impact climate change and how we can mitigate its effects.

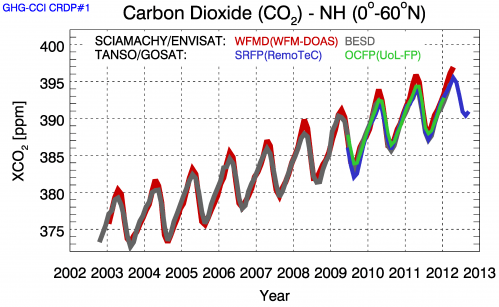

At the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, there were about 280 parts per million (ppm) of carbon dioxide in Earth’s atmosphere. As of today the CO2 level has risen to about 400 parts per million.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing OCO-2, GPM, Curiosity, Opportunity, Orion, SpaceX, Boeing, Orbital Sciences, MAVEN, MOM, Mars and more Earth & Planetary science and human spaceflight news.