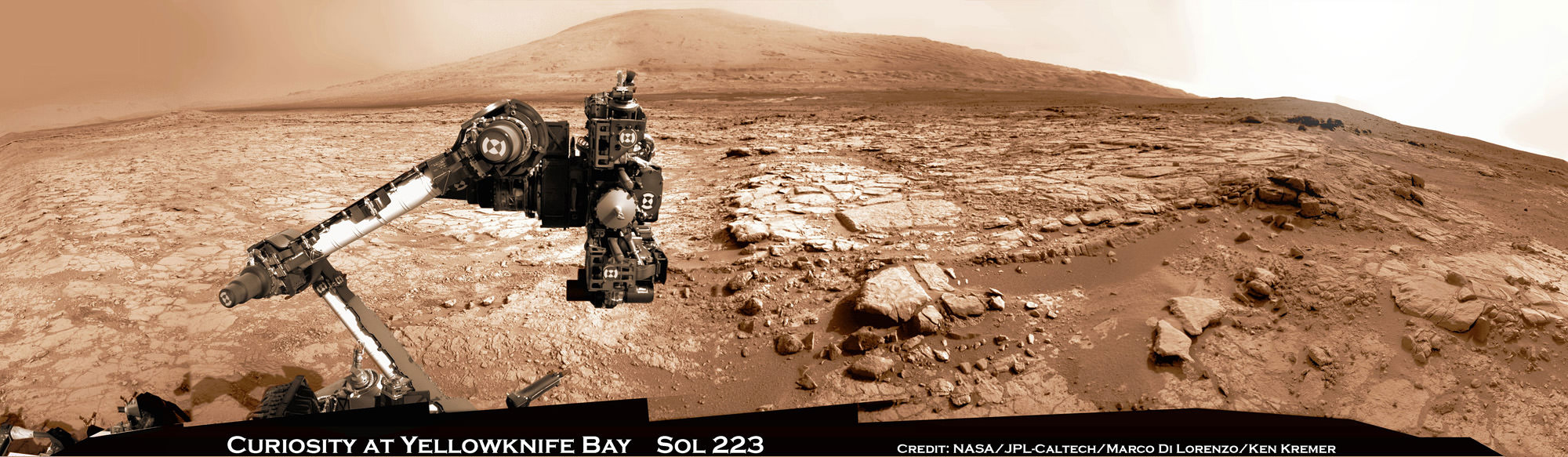

Curiosity and Mount Sharp – Parting Shot ahead of Mars Solar Conjunction

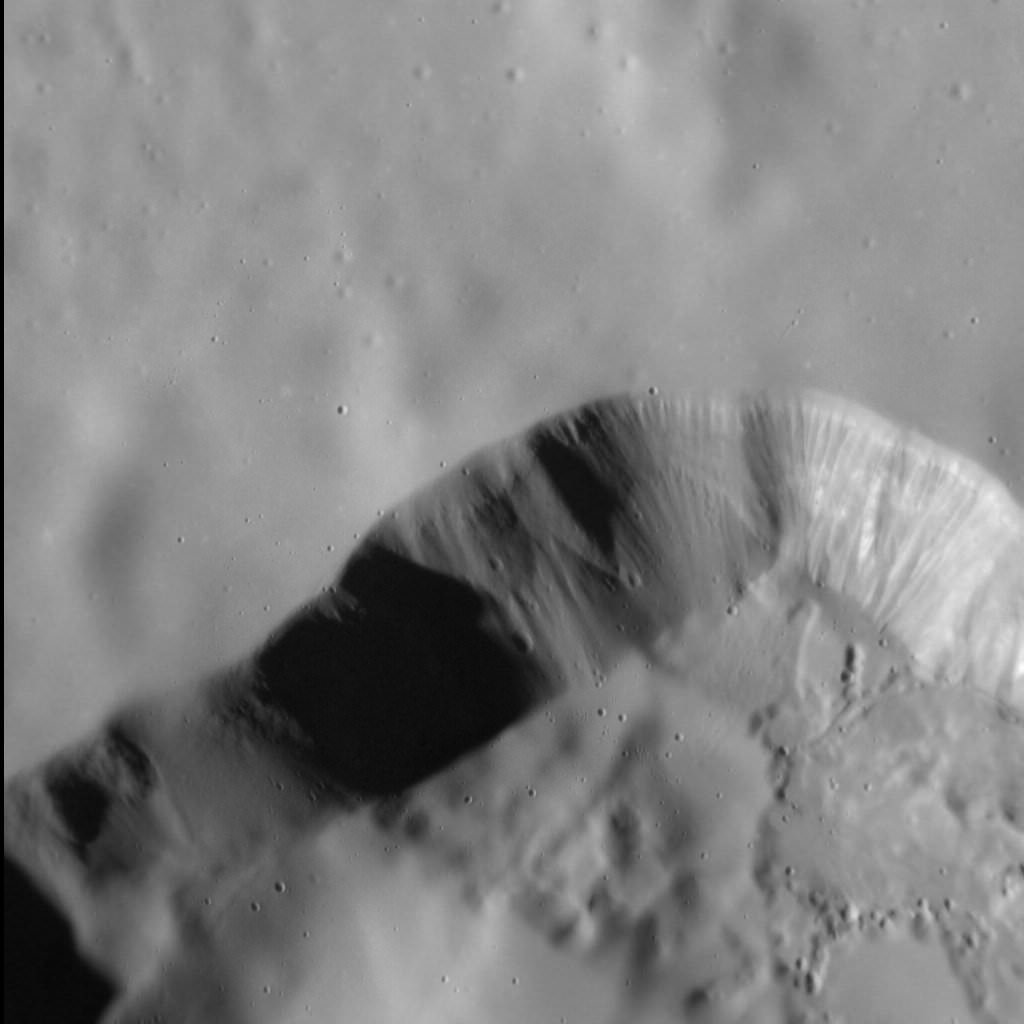

Enjoy this parting view of Curiosity’s elevated robotic arm and drill staring at you; back dropped with her ultimate destination – Mount Sharp – in this panoramic vista of Yellowknife Bay basin snapped on March 23, Sol 223, by the rover’s navigation camera system. The raw images were stitched by Marco Di Lorenzo and Ken Kremer and colorized. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Marco Di Lorenzo/KenKremer (kenkremer.com)

See video below explaining Mars Solar Conjunction[/caption]

Earth’s science invasion fleet at Mars is taking a break from speaking with their handlers back on Earth.

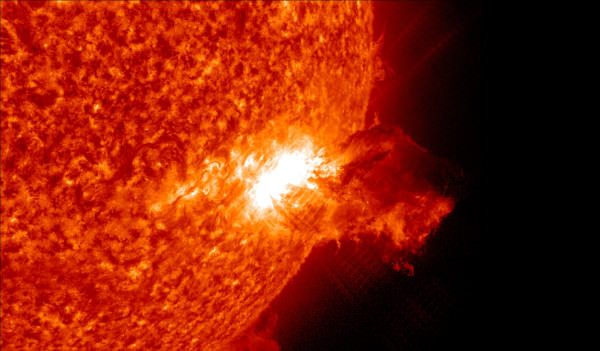

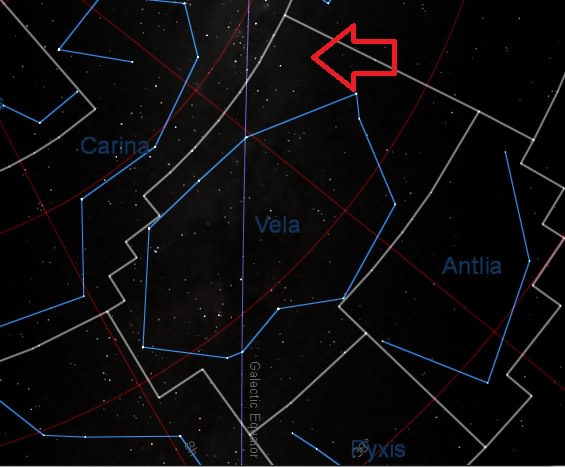

Why ? Because as happens every 26 months, the sun has gotten directly in the way of Mars and Earth.

Earth, Mars and the Sun are lined up in nearly a straight line. The geometry is normal and it’s called ‘Mars Solar Conjunction’.

Conjunction officially started on April 4 and lasts until around May 1.

From our perspective here on Earth, Mars will be passing behind the Sun.

Watch this brief NASA JPL video for an explanation of Mars Solar Conjunction.

Therefore the Terran fleet will be on its own for the next month since the sun will be blocking nearly all communications.

In fact since the sun can disrupt and garble communications, mission controllers will be pretty much suspending transmissions and commands so as not to inadvertently create serious problems that could damage the fleet in a worst case scenario.

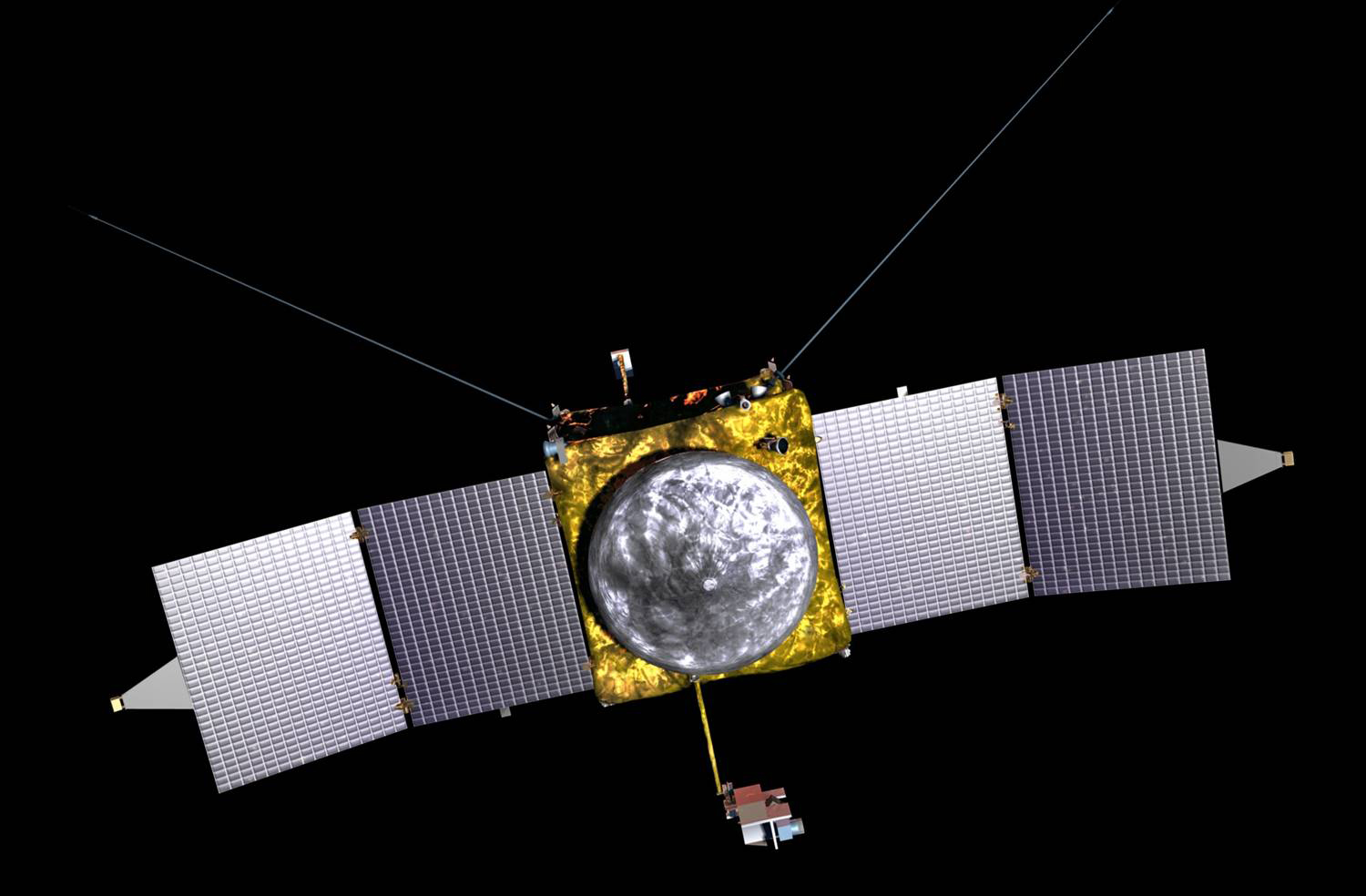

Right now there are a trio of orbiters and a duo of rovers from NASA and ESA exploring Mars.

The spacecraft include the Curiosity (MSL) and Opportunity (MER) rovers from NASA. Also the Mars Express orbiter from ESA and the Mars Odyssey (MO) and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) from NASA.

Because several of these robotic assets have been at Mars for nearly 10 years and longer, the engineering teams have a lot of experience with handling them during the month long conjunction period.

“This is our sixth conjunction for Odyssey,” said Chris Potts of JPL, mission manager for NASA’s Mars Odyssey, which has been orbiting Mars since 2001. “We have plenty of useful experience dealing with them, though each conjunction is a little different.”

But there is something new this go round.

“The biggest difference for this 2013 conjunction is having Curiosity on Mars,” Potts said. Odyssey and the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter relay almost all data coming from Curiosity and the Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity, as well as conducting the orbiters’ own science observations.

The rovers and orbiters can continue working and collecting science images and spectral data.

But that data will all be stored in the on board memory for a post-conjunction playback starting sometime in May.

…………….

Learn more about Curiosity’s groundbreaking discoveries and NASA missions at Ken’s upcoming lecture presentations:

April 20/21 : “Curiosity and the Search for Life on Mars – (in 3-D)”. Plus Orion, SpaceX, Antares, the Space Shuttle and more! NEAF Astronomy Forum, Suffern, NY

April 28: “Curiosity and the Search for Life on Mars – (in 3-D)”. Plus the Space Shuttle, SpaceX, Antares, Orion and more. Washington Crossing State Park, Titusville, NJ, 130 PM