Live on the wrong continent to witness the August 21st total solar eclipse? Well… celestial mechanics has a little consolation prize for Old World observers, with a partial lunar eclipse on the night of Monday into Tuesday, August 7/8th.

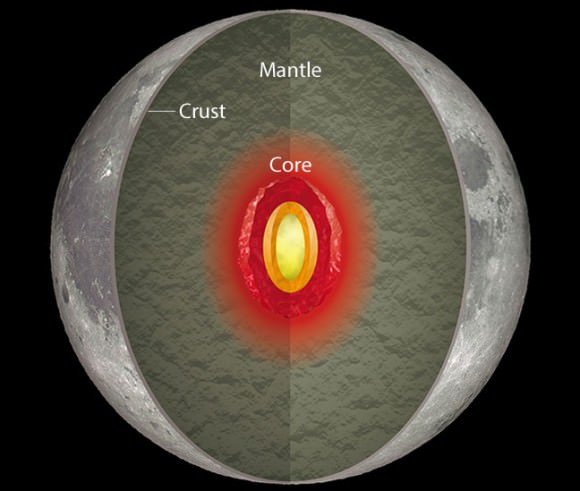

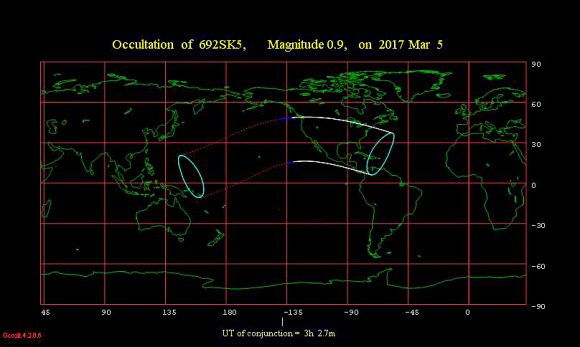

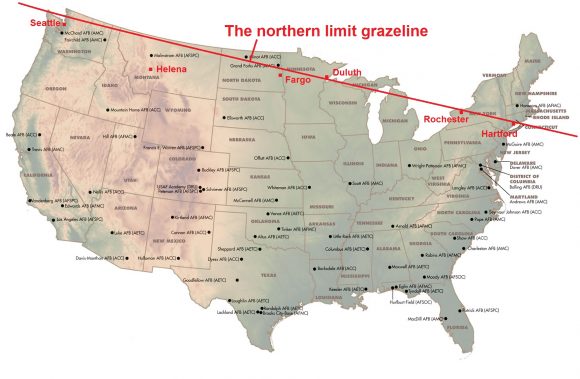

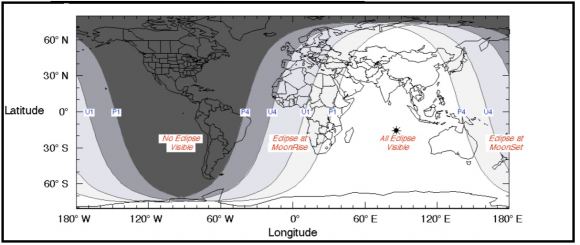

A partial lunar eclipse occurs when the Moon just nicks the inner dark core of the Earth’s shadow, known as the umbra. This eclipse is centered on the Indian Ocean region, with the event occurring at moonrise for the United Kingdom, Europe and western Africa and moonset/sunrise for New Zealand and Japan. Western Australia, southern Asia and eastern Africa will see the entire eclipse.

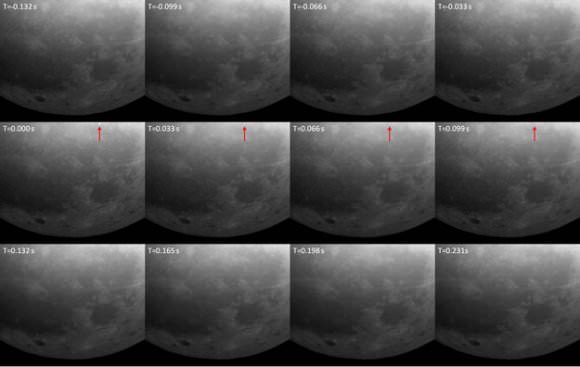

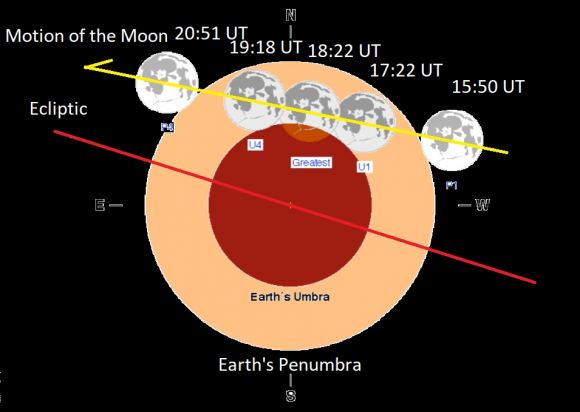

The penumbral phase of the eclipse begins on August 7th at 15:50 Universal Time (UT), though you probably won’t notice a slight tea colored shading on the face of the Moon until about half an hour in. The partial phases begin at 17:23 UT, when the ragged edge of the umbra becomes apparent on the southeastern limb of the Moon. The deepest partial eclipse occurs at 18:22 UT with 25% of the Moon submerged in the umbra. Partial phase lasts 116 minutes in duration, and the entire eclipse is about five hours long.

This also marks the start of the second and final eclipse season for 2017. Four eclipses occur this year: a penumbral lunar eclipse and annular solar eclipse this past February, and this month’s partial lunar and total solar eclipse.

Eclipses always occur in pairs, or very rarely triplets with an alternating lunar-solar pattern. This is because the tilt of the Moon’s orbit is inclined five degrees relative to the ecliptic, the plane of the Earth’s orbit around the Sun. The Moon therefore misses the 30′ wide disk of the Sun and the 80′ – 85′ wide inner shadow of the Earth on most passes.

Fun fact: at the Moon’s 240,000 mile distance from the Earth, the ratio of the apparent size of the Moon and the shadow is approximately equivalent to a basketball and a hoop.

When celestial bodies come into alignment, however, things can get interesting. For an eclipse to occur, the nodes – the point where the Moon’s orbit intersects the ecliptic – need to align with the position of the Moon and the Sun. There are two nodes, one descending with the Moon crossing the ecliptic from north to south, and one ascending. The time it takes for the Moon to return to the same node (27.2 days) is a draconitic month. Moreover, the nodes are moving around the Earth due to drag on the Moon’s orbit mainly by the Sun, and move all the way around the zodiac once every 18.6 years.

Got all that? Let’s put it into practice with this month’s eclipses. First, the Moon crosses its descending node at 10:56 UT on August 8th, just over 16 hours after Monday’s partial eclipse. Two weeks later, however, the Moon crosses ascending node just under eight hours from the central conjunction with the Sun, and a total solar eclipse occurs.

Tales of the Saros

The August 7th lunar eclipse is member number 62 of the 83 lunar eclipses in saros series 119, which started on October 14th, 935 AD and will end with a final shallow penumbral eclipse on March 25th, 2396 AD. If you witnessed the lunar eclipse of July 28th, 1999, then you saw the last lunar eclipse in the same saros. Saros 119 produced its last total lunar eclipse on June 15th, 1927.

The next lunar eclipse, a total occurs on January 31st, 2018, favoring the Pacific rim regions.

Partial lunar eclipses have occasionally work their way into history, usually as bad omens. One famous example is the partial lunar eclipse of May 22nd, 1453 which preceded the Fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks by a week. Apparently, a long standing legend claimed that a lunar eclipse would be the harbinger of the fall of Byzantium, and the partially eclipsed Moon rising over the besieged city ramparts seemed to fulfill the prophecy.

In our more enlightened age, we can simply enjoy Monday’s partial lunar eclipse as a fine celestial spectacle. You don’t need any special equipment to enjoy a lunar eclipse, just a view from the correct Moonward facing hemisphere of the Earth, and reasonably clear skies.

See the curve of the Earth’s shadow? This is one of the very few times that you can see that the Earth is indeed round (sorry, Flat Earthers) with your own eyes. And this curve is true for observers watching the Moon on the horizon, or high overhead near the zenith.

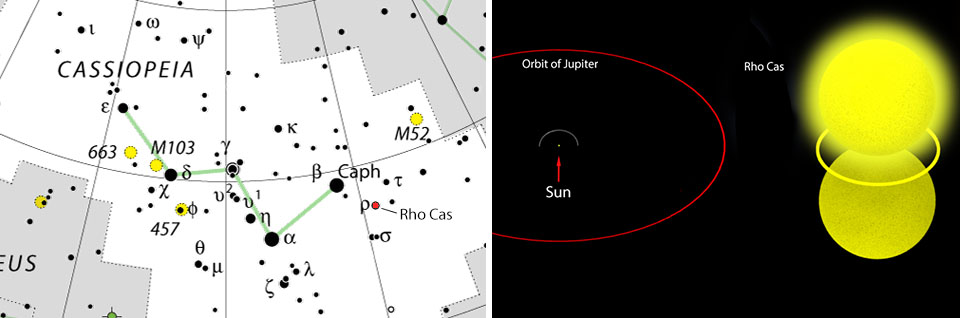

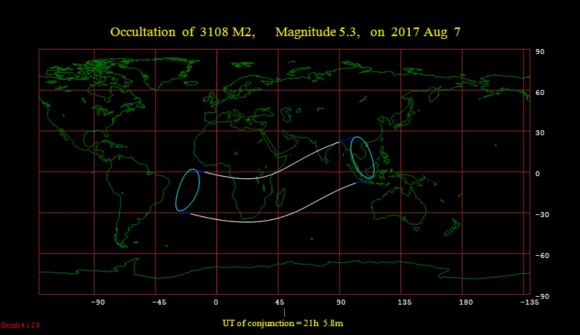

This month’s lunar eclipse occurs in the astronomical constellation of Capricornus. The Moon will also occult the +5th magnitude star 29 Capricorni for southern India, Madagascar and South Africa shortly after the eclipse.

Finally, anyone out there planning on carrying the partial lunar eclipse live, let us know… curiously, even Slooh seems to be sitting this one out.

Update: we have one possible broadcast, via Shahrin Ahmad (@shahgazer on Twitter). Updates to follow!

The final eclipse season for 2017 is now underway, starting Monday night. Nothing is more certain in this Universe than death, taxes and celestial mechanics, as the path of the Moon now sends it headlong to its August 21st destiny and the Great American Total Solar Eclipse.

-We’ll be posting on Universe Today once more pre-total solar eclipse one week prior, with weather predictions, solar and sunspot activity and prospects for viewing the eclipse from Earth and space and more!

-Read more about this year’s eclipses in our 2017 Guide to 101 Astronomical Events.

-Eclipse… science fiction? Read our original eclipse-fueled tales Exeligmos, Shadowfall, Peak Season and more!