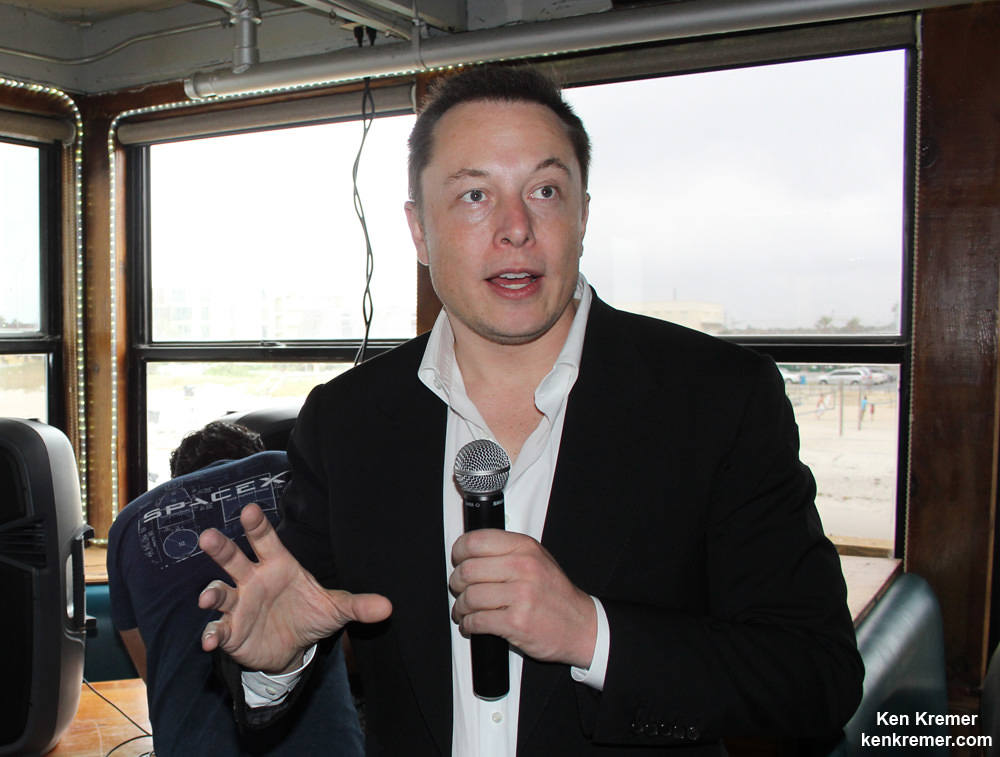

KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, FL – Elon Musk, billionaire founder and CEO of SpaceX, announced today (27 Feb) a daring plan to launch a commercial manned journey “to beyond the Moon and back” in 2018 flying aboard an advanced crewed Dragon spacecraft paid for by two private astronauts – at a media telecon.

Note: Check back again for updated details on this breaking news story.

“This is an exciting thing! We have been approached to do a crewed mission to beyond the Moon by some private individuals,” Musk announced at the hastily arranged media telecon just concluded this afternoon which Universe Today was invited to participate in.

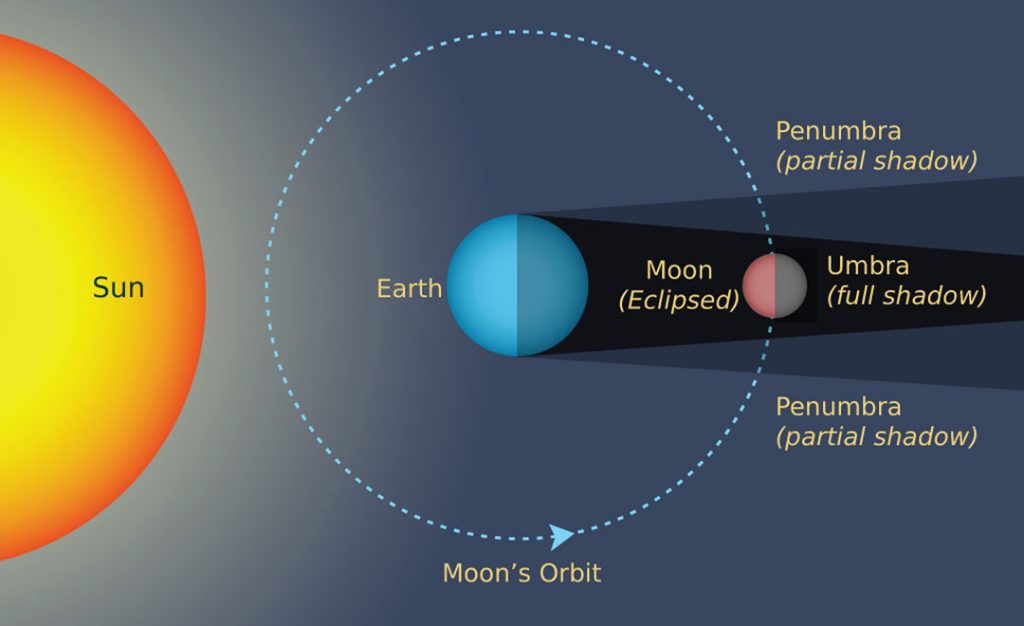

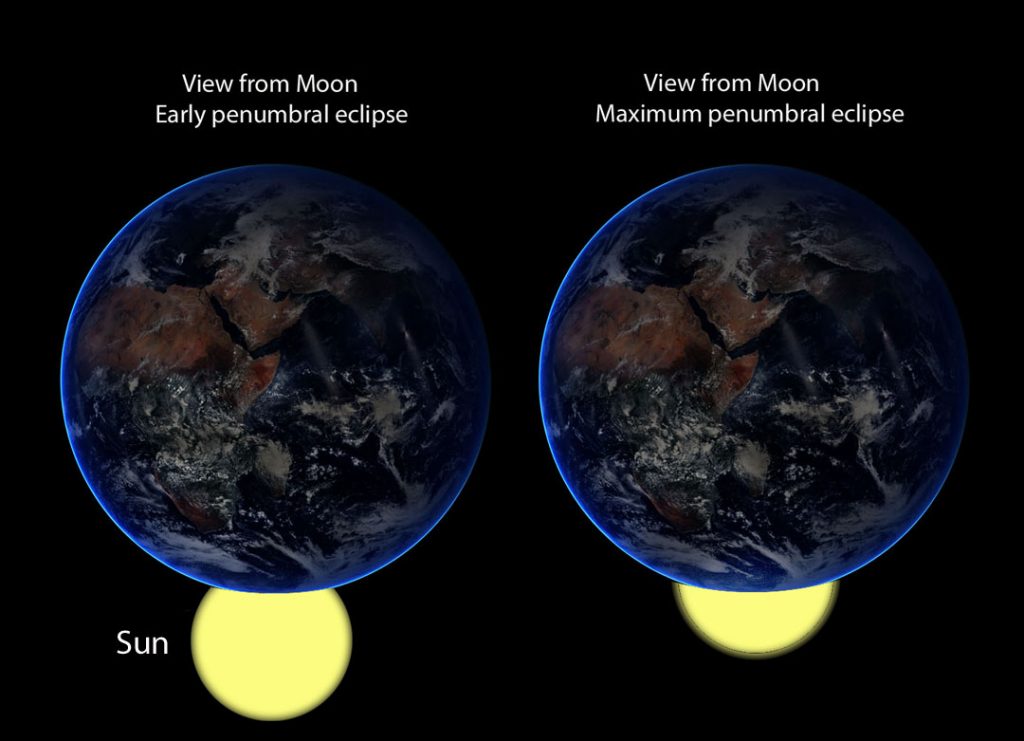

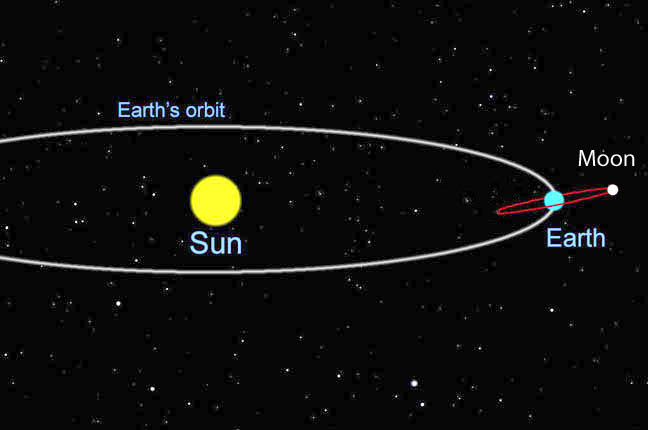

The private two person crew would fly aboard a human rated Dragon on a long looping trajectory around the moon and far beyond on an ambitious mission lasting roughly eight days and that could blastoff by late 2018 – if all goes well with rocket and spacecraft currently under development, but not yet flown.

“This would do a long leap around the moon,” Musk said. “We’re working out the exact parameters, but this would be approximately a week long mission – and it would skim the surface of the moon, go quite a bit farther out into deep space, and then loop back to Earth. I’m guessing probably distance wise, maybe 300,000 or 400,000 miles.”

The private duo would fly on a ‘free return’ trajectory around the Moon – but not land on the Moon like NASA did in the 1960s and 1970s.

But they would venture further out into deep space than any humans have ever been before.

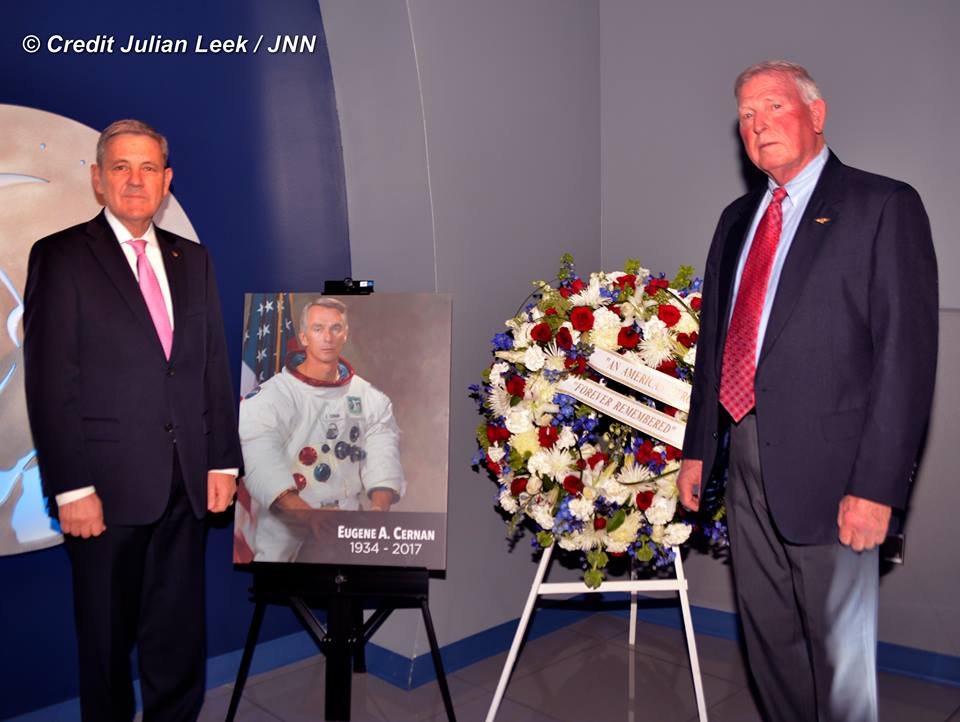

No human has traveled beyond low Earth orbit in more than four decades since Apollo 17 – NASA’s final lunar landing mission in December 1972, and commanded by recently deceased astronaut Gene Cernan.

“Like the Apollo astronauts before them, these individuals will travel into space carrying the hopes and dreams of all humankind, driven by the universal human spirit of exploration,” says SpaceX.

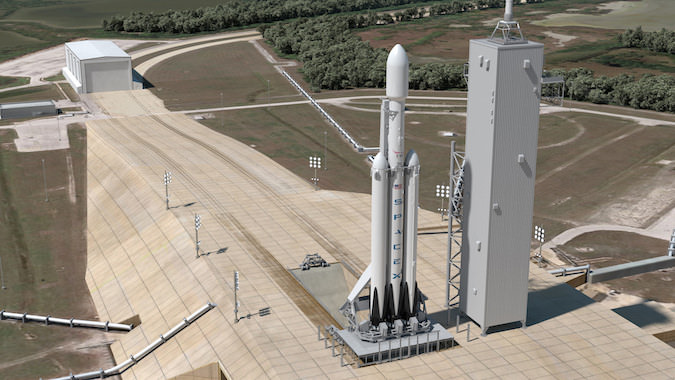

Musk said the private crew of two would launch on a Dragon 2 crew spacecraft atop a SpaceX Falcon Heavy booster from historic pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida – the same pad that just reopened for business last week with the successful launch of a cargo Dragon to the International Space Station (ISS) for NASA on the CRS-10 mission.

“They are two paying customers,” Musk elaborated. “They’re very serious about it.”

“But nobody from Hollywood.”

“They will fly using a Dragon 2 and Falcon Heavy next year in 2018.”

“The lunar orbit mission would launch about 6 months after the [first] NASA crew to the space station on Falcon 9/Dragon 2,” Musk told Universe Today.

Musk noted they had put down “a significant deposit” and will undergo extensive flight training.

He declined to state the cost – but just mentioned it would be more than the cost of a Dragon seat for a flight to the space station, which is about $58 million.

SpaceX is currently developing the commercial crew Dragon spacecraft for missions to transport astronauts to low Earth orbit (LEO) and the International Space Station (ISS) under a NASA funded a $2.6 billion public/private contract. Boeing was also awarded a $4.2 Billion commercial crew contract by NASA to build the crewed CST-100 Starliner for ISS missions.

The company is developing the triple barreled Falcon Heavy with its own funds – which is derived from the single barreled Falcon 9 rocket funded by NASA.

But neither the Dragon 2 nor the Falcon Heavy have yet launched to space and their respective maiden missions haven been postponed multiple time for several years – due to a combination of funding and technical issues.

So alot has to go right for this private Moonshot mission to actually lift off by the end of next year.

NASA is developing the new SLS heavy lift booster and Orion capsule for deep space missions to the Moon, Asteroids and Mars.

The inaugural uncrewed SLS/Orion launch is slated for late 2018. But NASA just announced the agency has started a feasibility study to examine launching a crew on the first Orion dubbed Exploration Mission-1 (EM-1) on a revamped mission in 2019 rather than 2021 on EM-2.

Thus the potential exists that SpaceX could beat NASA back to the Moon with humans.

I asked Musk to describe the sequence of launches leading up to the private Moonshot and whether a crewed Dragon 2 would launch initially to the ISS.

Musk replied that SpaceX hopes to launch the first uncrewed Dragon 2 test flight to the ISS by the end of this year on the firm’s Falcon 9 rocket – almost identical to the rocket that just launched on Feb. 19 from pad 39A.

That would be followed by crewed launch to the ISS around mid-2018 and the private Moonshot by the end of 2018.

“The timeline is we expect to launch a human rated Dragon 2 on Falcon 9 by the end of this year, but without people on board just for the test flight to the space station,” Musk told Universe Today.

“Then about 6 months later we would fly with a NASA crew to the space station on Falcon 9/Dragon 2.”

“And then about 6 months after that, assuming the schedule holds by end of next year, is when we would do the lunar orbit mission.”

I asked Musk about whether any heat shield modifications to Dragon 2 were required?

“The heat shield is quite massively over designed,” Musk told me during the telecom.

“It’s actually designed for multiple Earth orbit reentry missions – so that we can actually do up to 10 reentry missions with the same heat shield.”

“That means it can actually do at least 1 lunar orbit reentry velocity missions, and conceivably maybe 2.”

“So we do not expect any redesign of the heat shield.”

The reentry velocity and heat generated from a lunar mission is far higher than from a low Earth orbit mission to the space station.

Nevertheless the flight is not without risk.

The Dragon 2 craft will need some upgrades. For example “a deep space communications system” with have to be installed for longer trips, said Musk.

Dragon currently is only equipped for shorter Earth orbiting missions.

The flight must also be approved by the FAA before its allowed to blastoff – as is the case with all commercial launches like the Feb. 19 Falcon 9/Cargo Dragon mission for NASA.

Musk declined to identify the two individuals or their genders but did say they know one another.

They must pass health and training tests.

“We expect to conduct health and fitness tests, as well as begin initial training later this year,’ noted SpaceX.

The flight itself would be very autonomous. The private passengers will train for emergencies but would not be responsible for piloting Dragon.

Musk said he would give top priority to NASA astronauts for the Moonshot mission if the agency wanted to procure the seats ahead of the private passengers.

He noted that SpaceX would have the capability to launch one or 2 private moonshots per year.

“I think this should be a really exciting mission that gets the world really excited about sending people into deep space again. I think it should be super inspirational,” Musk said.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and Planetary science and human spaceflight news.