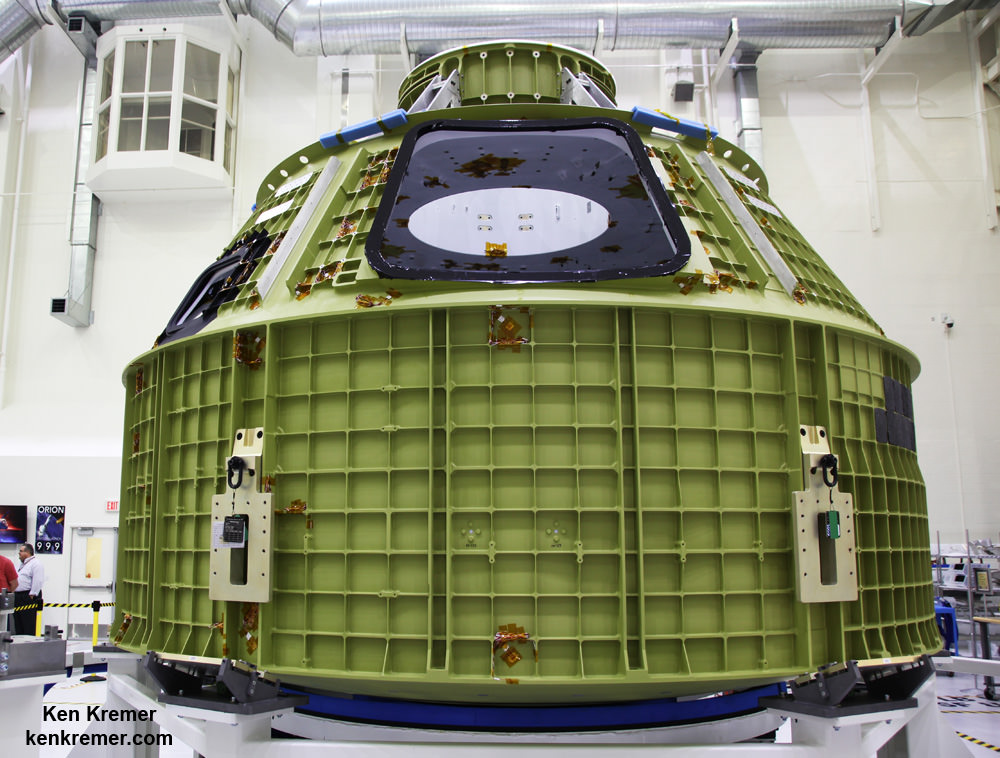

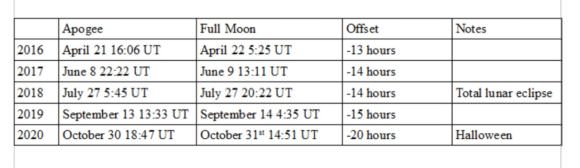

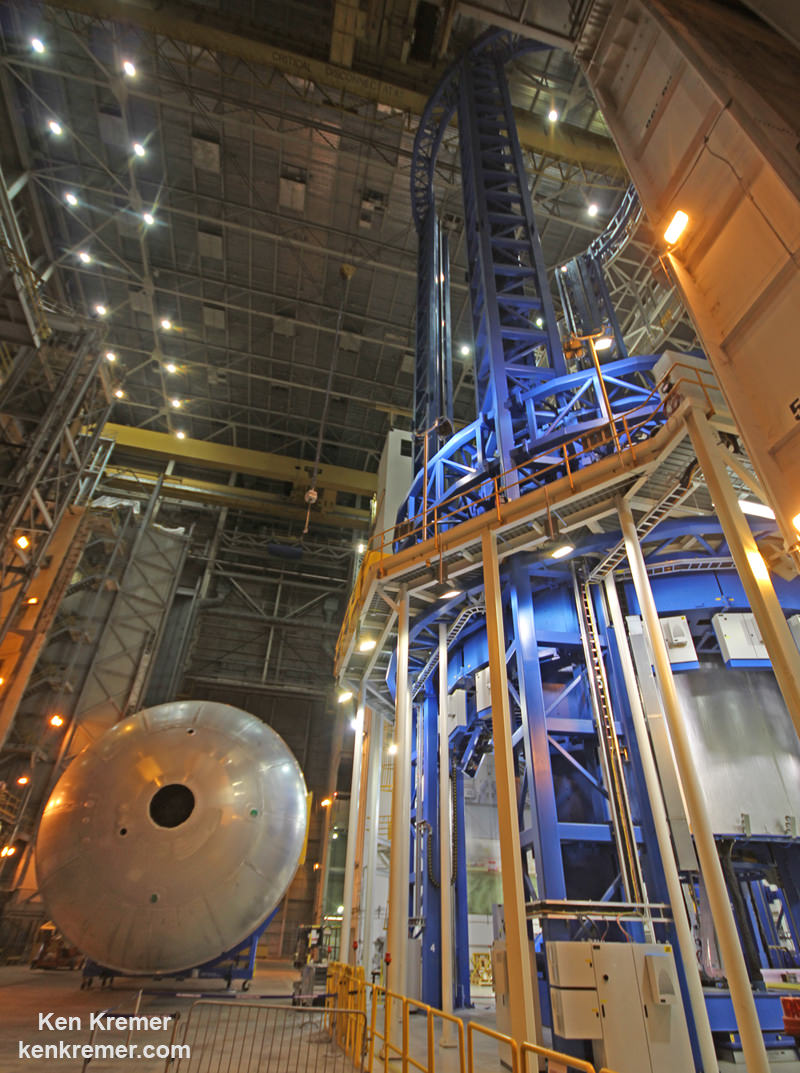

MICHOUD ASSEMBLY FACILITY, NEW ORLEANS, LA – NASA has just finished welding together the very first fuel tank for America’s humongous Space Launch System (SLS) deep space rocket currently under development – and Universe Today had an exclusive up close look at the liquid hydrogen (LH2) test tank shortly after its birth as well as the first flight tank, during a tour of NASA’s New Orleans rocket manufacturing facility on Friday, July 22, shortly after completion of the milestone assembly operation.

“We have just finished welding the first liquid hydrogen qualification tank article …. and are in the middle of production welding of the first liquid hydrogen flight hardware tank [for SLS-1] in the big Vertical Assembly Center welder!” explained Patrick Whipps, NASA SLS Stages Element Manager, in an exclusive hardware tour and interview with Universe Today on July 22, 2016 at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility (MAF) in New Orleans.

“We are literally putting the SLS rocket hardware together here at last. All five elements to put the SLS stages together [at Michoud].”

This first fully welded SLS liquid hydrogen tank is known as a ‘qualification test article’ and it was assembled using basically the same components and processing procedures as an actual flight tank, says Whipps.

“We just completed the liquid hydrogen qualification tank article and lifted it out of the welding machine and put it into some cradles. We will put it into a newly designed straddle carrier article next week to transport it around safely and reliably for further work.”

And welding of the liquid hydrogen flight tank is moving along well.

“We will be complete with all SLS core stage flight tank welding in the VAC by the end of September,” added Jackie Nesselroad, SLS Boeing manager at Michoud. “It’s coming up very quickly!”

“The welding of the forward dome to barrel 1 on the liquid hydrogen flight tank is complete. And we are doing phased array ultrasonic testing right now!”

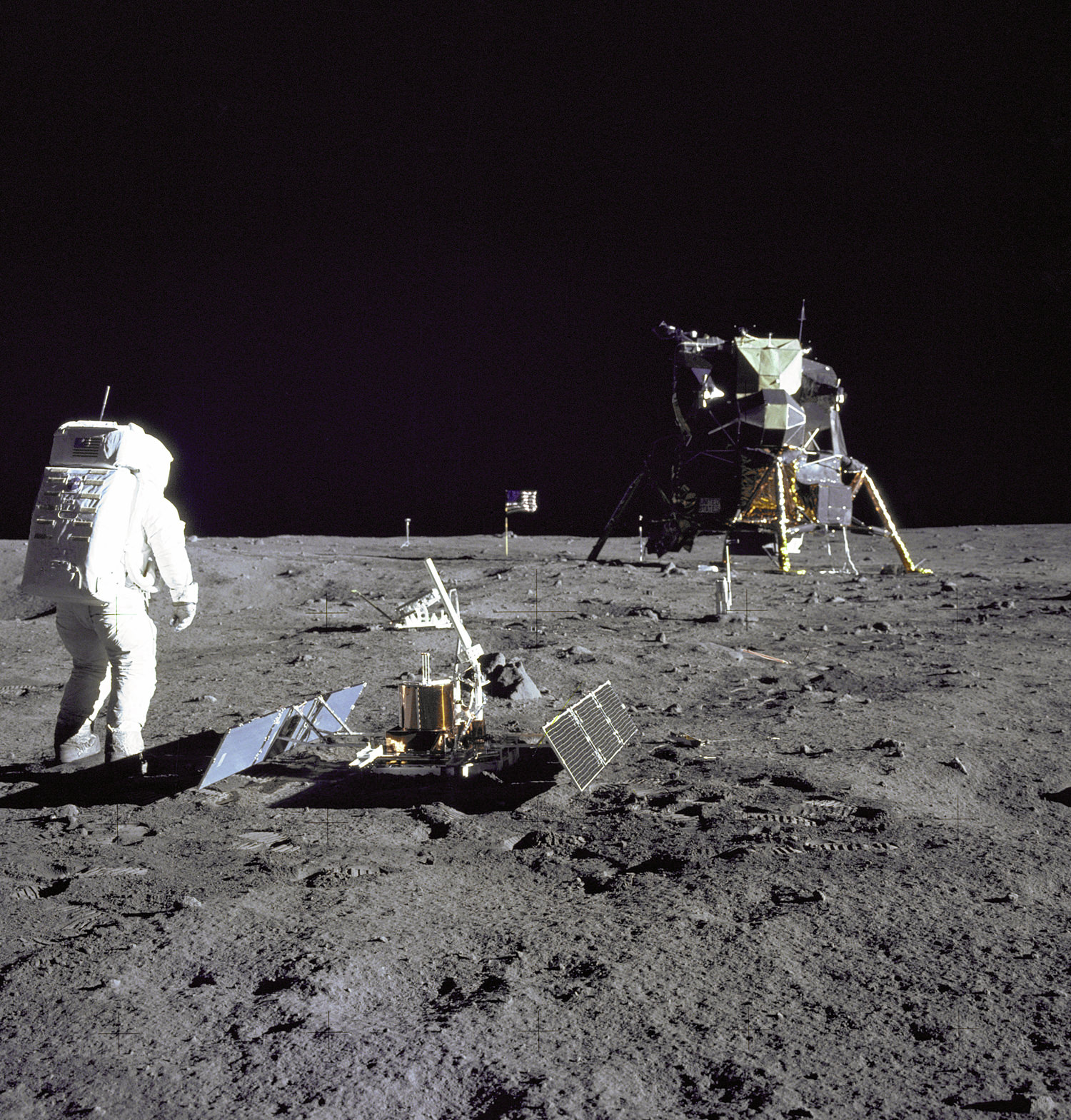

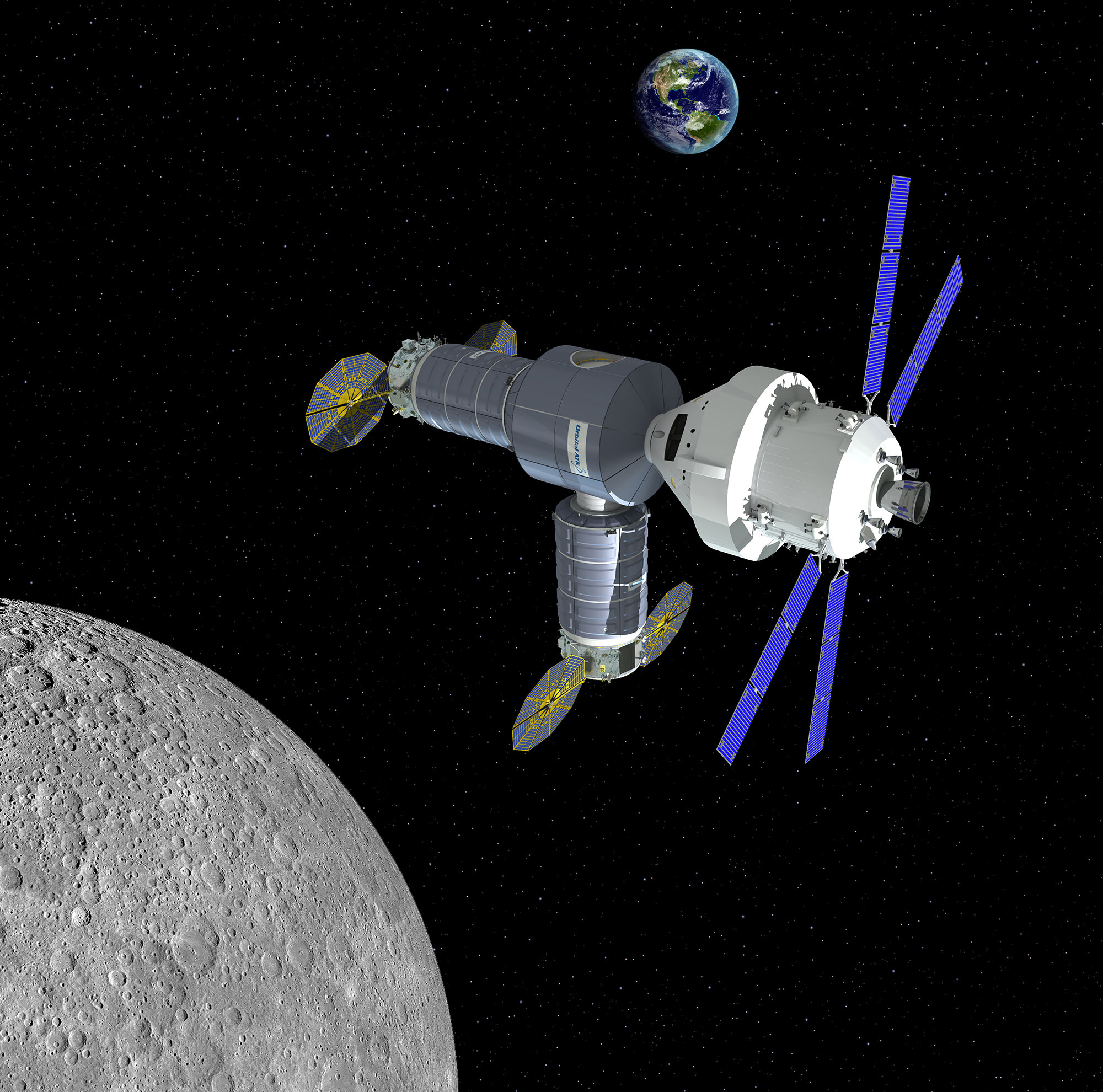

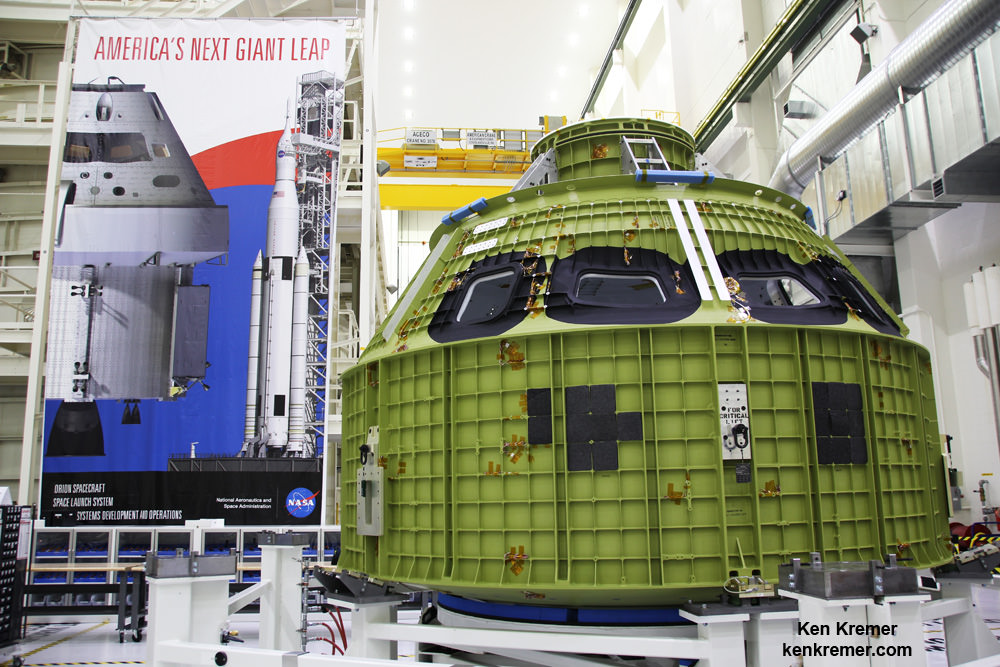

SLS is the most powerful booster the world has even seen and one day soon will propel NASA astronauts in the agency’s Orion crew capsule on exciting missions of exploration to deep space destinations including the Moon, Asteroids and Mars – venturing further out than humans ever have before!

The LH2 ‘qualification test article’ was welded together using the world’s largest welder – known as the Vertical Assembly Center, or VAC, at Michoud.

And it’s a giant! – measuring approximately 130-feet in length and 27.6 feet (8.4 m) in diameter.

See my exclusive up close photos herein documenting the newly completed tank as the first media to visit the first SLS tank. I saw the big tank shortly after it was carefully lifted out of the welder and placed horizontally on a storage cradle on Michoud’s factory floor.

Finishing its assembly after years of meticulous planning and hard work paves the path to enabling the maiden test launch of the SLS heavy lifter in the fall of 2018 from the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida.

The qual test article is the immediate precursor to the actual first LH2 flight tank now being welded.

“We will finish welding the liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen flight tanks by September,” Whipps told Universe Today.

Technicians assembled the LH2 tank by feeding the individual metallic components into NASA’s gigantic “Welding Wonder” machine – as its affectionately known – at Michoud, thus creating a rigid 13 story tall structure.

The welding work was just completed this past week on the massive silver colored structure. It was removed from the VAC welder and placed horizontally on a cradle.

I watched along as the team was also already hard at work fabricating SLS’s first liquid hydrogen flight article tank in the VAC, right beside the qualification tank resting on the floor.

Welding of the other big fuel tank, the liquid oxygen (LOX) qualification and flight article tanks will follow quickly inside the impressive ‘Welding Wonder’ machine, Nesselroad explained.

The LH2 and LOX tanks sit on top of one another inside the SLS outer skin.

The SLS core stage – or first stage – is mostly comprised of the liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen cryogenic fuel storage tanks which store the rocket propellants at super chilled temperatures. Boeing is the prime contractor for the SLS core stage.

To prove that the new welding machines would work as designed, NASA opted “for a 3 stage assembly philosophy,” Whipps explained.

Engineers first “welded confidence articles for each of the tank sections” to prove out the welding techniques “and establish a learning curve for the team and test out the software and new weld tools. We learned a lot from the weld confidence articles!”

“On the heels of that followed the qualification weld articles” for tank loads testing.

“The qualification articles are as ‘flight-like’ as we can get them! With the expectation that there are still some tweaks coming.”

“And finally that leads into our flight hardware production welding and manufacturing the actual flight unit tanks for launches.”

“All the confidence articles and the LH2 qualification article are complete!”

What’s the next step for the LH2 tank?

The test article tank will be outfitted with special sensors and simulators attached to each end to record reams of important engineering data, thereby extending it to about 185 feet in length.

Thereafter it will loaded onto the Pegasus barge and shipped to NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, for structural loads testing on one of two new test stands currently under construction for the tanks. The tests are done to prove that the tanks can withstand the extreme stresses of spaceflight and safely carry our astronauts to space.

“We are manufacturing the simulators for each of the SLS elements now for destructive tests – for shipment to Marshall. It will test all the stress modes, and finally to failure to see the process margins.”

The SLS core stage builds on heritage from NASA’s Space Shuttle Program and is based on the shuttle’s External Tank (ET). All 135 ET flight units were built at Michoud during the thirty year long shuttle program by Lockheed Martin.

“We saved billions of dollars and years of development effort vs. starting from a clean sheet of paper design, by taking aspects of the shuttle … and created an External Tank type generic structure – with the forward avionics on top and the complex engine section with 4 engines (vs. 3 for shuttle) on the bottom,” Whipps elaborated.

“This is truly an engineering marvel like the External Tank was – with its strength that it had and carrying the weight that it did. If you made our ET the equivalent of a Coke can, our thickness was about 1/5 of a coke can.”

“It’s a tremendous engineering job. But the ullage pressures in the LOX and LH2 tanks are significantly more and the systems running down the side of the SLS tank are much more sophisticated. Its all significantly more complex with the feed lines than what we did for the ET. But we brought forward the aspects and designs that let us save time and money and we knew were effective and reliable.”

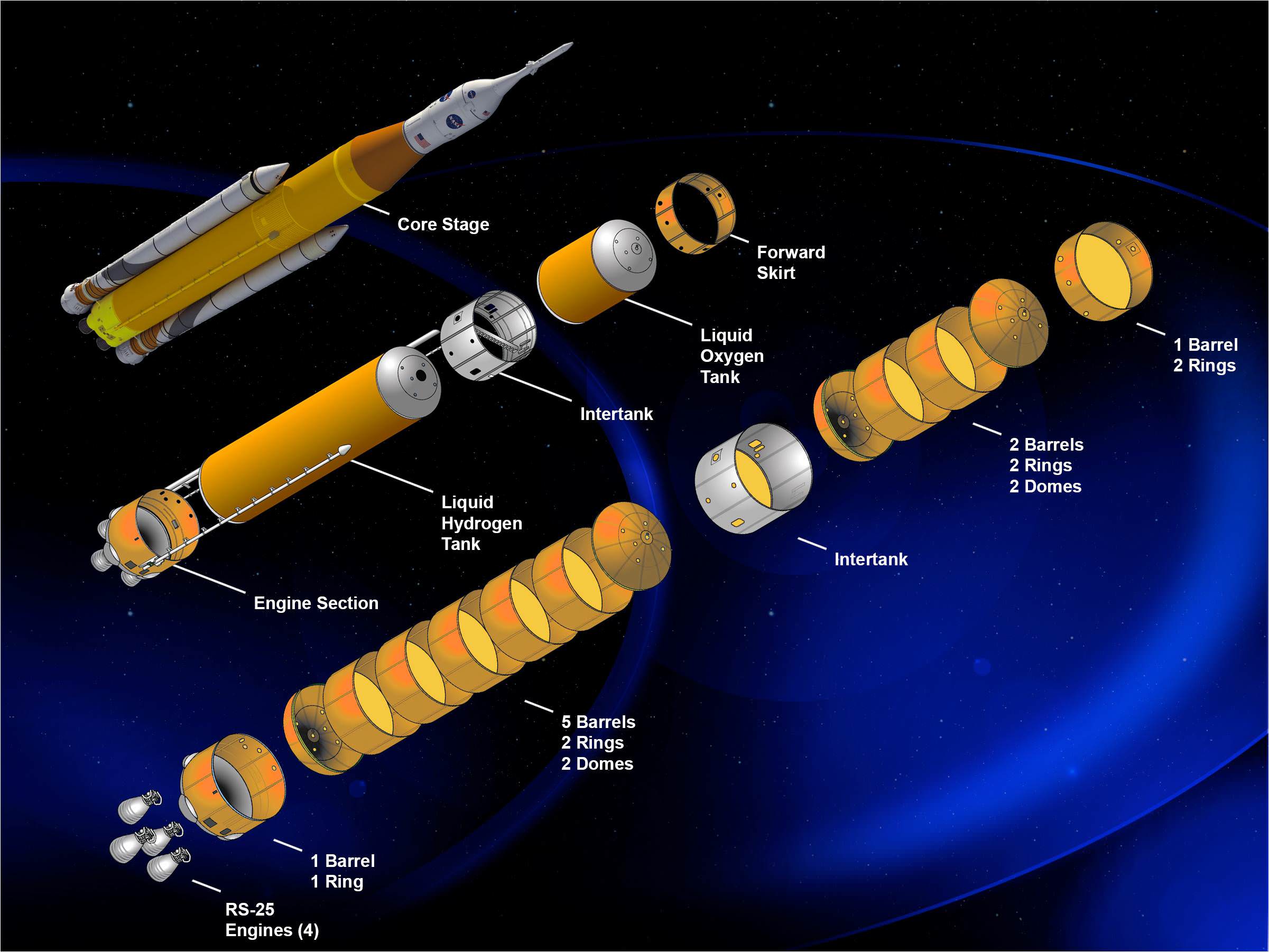

The SLS core stage is comprised of five major structures: the forward skirt, the liquid oxygen tank (LOX), the intertank, the liquid hydrogen tank (LH2) and the engine section.

The LH2 and LOX tanks feed the cryogenic propellants into the first stage engine propulsion section which is powered by a quartet of RS-25 engines – modified space shuttle main engines (SSMEs) – and a pair of enhanced five segment solid rocket boosters (SRBs) also derived from the shuttles four segment boosters.

The tanks are assembled by joining previously manufactured dome, ring and barrel components together in the Vertical Assembly Center by a process known as friction stir welding. The rings connect and provide stiffness between the domes and barrels.

The LH2 tank is the largest major part of the SLS core stage. It holds 537,000 gallons of super chilled liquid hydrogen. It is comprised of 5 barrels, 2 domes, and 2 rings.

The LOX tank holds 196,000 pounds of liquid oxygen. It is assembled from 2 barrels, 2 domes, and 2 rings and measures over 50 feet long.

The material of construction of the tanks has changed compared to the ET.

“The tanks are constructed of a material called the Aluminum 2219 alloy,” said Whipps. “It’s a ubiquosly used aerospace alloy with some copper but no lithium, unlike the shuttle superlightweight ET tanks that used Aluminum 2195. The 2219 has been a success story for the welding. This alloy is heavier but does not affect our payload potential.”

“The intertanks are the only non welded structure. They are bolted together and we are manufacturing them also. It’s much heavier and thicker.”

Overall, the SLS core stage towers over 212 feet (64.6 meters) tall and sports a diameter of 27.6 feet (8.4 m).

NASA’s Vehicle Assembly Center is the world’s largest robotic weld tool. The domes and barrels are assembled from smaller panels and piece parts using other dedicated robotic welding machines at Michoud.

The total weight of the whole core stage empty is 188,000 pounds and 2.3 million pounds when fully loaded with propellant. The empty ET weighed some 55,000 pounds.

Considering that the entire Shuttle ET was 154-feet long, the 130-foot long LH2 tank alone isn’t much smaller and gives perspective on just how big it really is as the largest rocket fuel tank ever built.

“So far all the parts of the SLS rocket are coming along well.”

“The Michoud SLS workforce totals about 1000 to 1500 people between NASA and the contractors.”

Every fuel tank welded together from now on after this series of confidence and qualification LOX and LH2 tanks will be actual flight article tanks for SLS launches.

“There are no plans to weld another qualification tank after this,” Nesselroad confirmed to me.

What’s ahead for the SLS-2 core stage?

“We start building the second SLS flight tanks in October of this year – 2016!” Nesselroad stated.

The world’s largest welder was specifically designed to manufacture the core stage of the world’s most powerful rocket – NASA’s SLS.

The Vertical Assembly Center welder was officially opened for business at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans on Friday, Sept. 12, 2014.

NASA Administrator Charles Bolden was personally on hand for the ribbon-cutting ceremony at the base of the huge VAC welder.

The state-of-the-art welding giant stands 170 feet tall and 78 feet wide. It complements the world-class welding toolkit being used to assemble various pieces of the SLS core stage including the domes, rings and barrels that have been previously manufactured.

The maiden test flight of the SLS/Orion is targeted for no later than November 2018 and will be configured in its initial 70-metric-ton (77-ton) Block 1 configuration with a liftoff thrust of 8.4 million pounds – more powerful than NASA’s Saturn V moon landing rocket.

Although the SLS-1 flight in 2018 will be uncrewed, NASA plans to launch astronauts on the SLS-2/EM-2 mission slated for the 2021 to 2023 timeframe.

The exact launch dates fully depend on the budget NASA receives from Congress and who is elected President in the November 2016 election – and whether they maintain or modify NASA’s objectives.

“If we can keep our focus and keep delivering, and deliver to the schedules, the budgets and the promise of what we’ve got, I think we’ve got a very capable vision that actually moves the nation very far forward in moving human presence into space,” said William Gerstenmaier, associate administrator for the Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington, during the post QM-2 SRB test media briefing in Utah last month.

“This is a very capable system. It’s not built for just one or two flights. It is actually built for multiple decades of use that will enable us to eventually allow humans to go to Mars in the 2030s.”

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and Planetary science and human spaceflight news.

………….

Learn more about SLS and Orion crew vehicle, SpaceX CRS-9 rocket launch, ISS, ULA Atlas and Delta rockets, Juno at Jupiter, Orbital ATK Antares & Cygnus, Boeing, Space Taxis, Mars rovers, NASA missions and more at Ken’s upcoming outreach events:

July 27-28: “ULA Atlas V NRO Spysat launch July 28, SpaceX launch to ISS on CRS-9, SLS, Orion, Juno at Jupiter, ULA Delta 4 Heavy NRO spy satellite, Commercial crew, Curiosity explores Mars, Pluto and more,” Kennedy Space Center Quality Inn, Titusville, FL, evenings