We always see the same side of the Moon. It’s always up there, staring down at us with its terrifying visage. Or maybe it’s a creepy rabbit? Anyway, it’s always showing us the same face, and never any other part.

This is because the Moon is tidally locked to the Earth; the same fate that affects every single large moon orbiting a planet. The Moon is locked to the Earth, the Jovian moons are locked to Jupiter, Titan is locked to Saturn, etc.

As the Moon orbits the Earth, it slowly rotates to keep the same hemisphere facing us. Its day is as long as its year. And standing on the surface of the Moon, you’d see the Earth in roughly the same spot in the sky. Forever and ever.

We see this all across the Solar System.

But there’s one place where this tidal locking goes to the next level: the dwarf planet Pluto and its large moon Charon are tidally locked to each other. In other words, the same hemisphere of Pluto always faces Charon and vice versa.

It take Pluto about 6 and a half days for the Sun to return to the same point in the sky, which is the same time it takes Charon to complete an orbit, which is the same time it takes the Sun to pass through the sky on Charon.

Since Pluto eventually locked to its moon, can the same thing happen here on Earth. Will we eventually lock with the Moon?

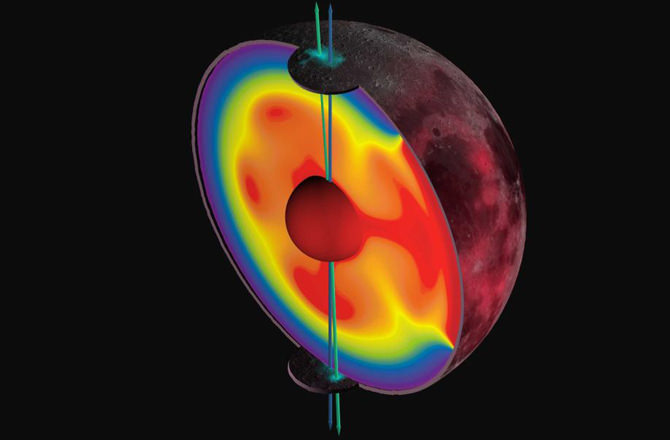

Before we answer this question, let’s explain what’s going on here. Although the Earth and the Moon are spheres, they actually have a little variation. The gravity pulling on each world creates love handle tidal bulges on each world.

And these bulges act like a brake, slowing down the rotation of the world. Because the Earth has 81 times the mass of the Moon, it was the dominant force in this interaction.

In the early Solar System, both the Earth and the Moon rotated independently. But the Earth’s gravity grabbed onto those love handles and slowed down the rotation of the Moon. To compensate for the loss of momentum in the system, the Moon drifted away from the Earth to its current position, about 370,000 kilometers away.

But Moon has the same impact on the Earth. The same tidal forces that cause the tides on Earth are slowing down the Earth’s rotation bit by bit. And the Moon is continuing to drift away a few centimeters a year to compensate.

It’s hard to estimate exactly when, but over the course of tens of billions of years, the Earth will become locked to the Moon, just like Pluto and Charon.

Of course, this will be long after the Sun has died as a red giant. And there’s no way to know what kind of mayhem that’ll cause to the Earth-Moon system. Other planets in the Solar System may shift around, and maybe even eject the Earth into space, taking the Moon with it.

What about the Sun? Is it possible for the Earth to eventually lock gravitationally to the Sun?

Astronomers have found extrasolar planets orbiting other stars which are tidally locked. But they’re extremely close, well within the orbit of Mercury.

Here in our Solar System, we’re just too far away from the Sun for the Earth to lock to it. The gravitational influence of the other planets like Venus, Mars and Jupiter perturb our orbit and keep us from ever locking. Without any other planets in the Solar System, though, and with a Sun that would last forever, it would be an inevitability.

It is theoretically possible that the Earth will tidally lock to the Moon in about 50 billion years or so. Assuming the Earth and Moon weren’t consumed during the Sun’s red giant phase. I guess we’ll have to wait and see.