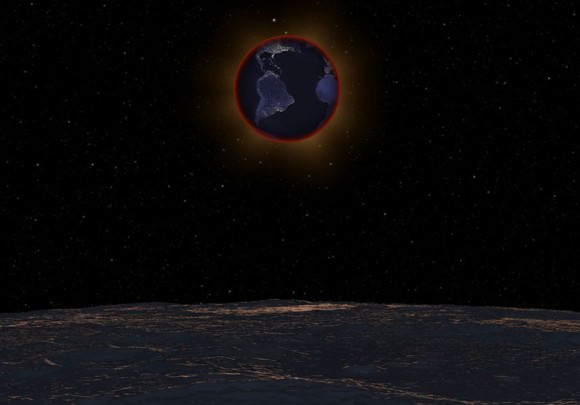

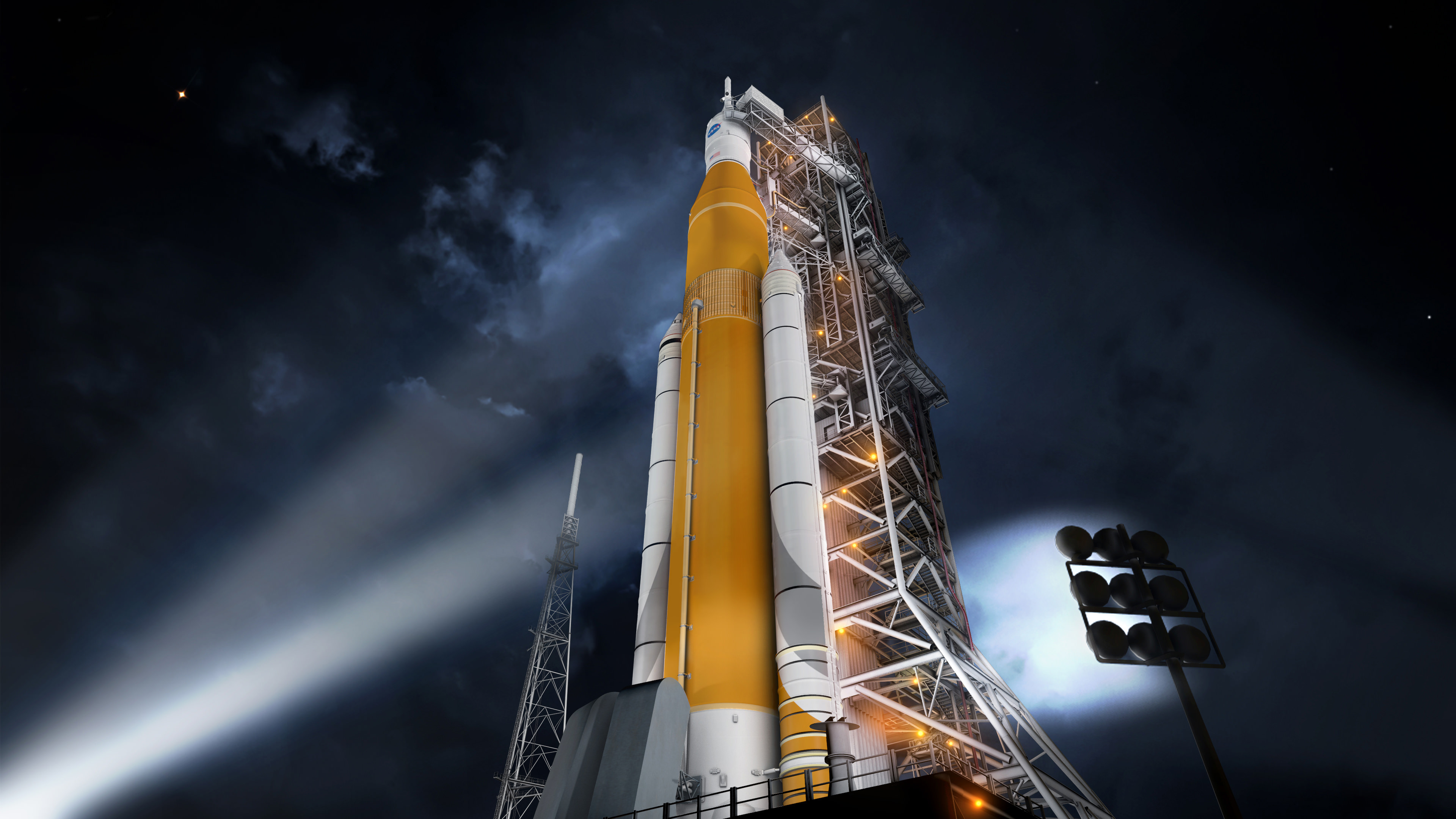

NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) blasts off from launch pad 39B at the Kennedy Space Center in this artist rendering showing a view of the liftoff of the Block 1 70-metric-ton (77-ton) crew vehicle configuration. Credit: NASA/MSFC

Story/imagery updated[/caption]

The SLS, America’s first human-rated heavy lift rocket intended to carry astronauts to deep space destinations since NASA’s Apollo moon landing era Saturn V, has passed a key design milestone known as the critical design review (CDR) thereby clearing the path to full scale fabrication.

NASA also confirmed they have dropped the Saturn V white color motif of the mammoth rocket in favor of burnt orange to reflect the natural color of the SLS boosters first stage cryogenic core. The agency also decided to add stripes to the huge solid rocket boosters.

NASA announced that the Space Launch System (SLS) has “completed all steps needed to clear a critical design review (CDR)” – meaning that the design of all the rockets components are technically acceptable and the agency can continue with full scale production towards achieving a maiden liftoff from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida in 2018.

“We’ve nailed down the design of SLS,” said Bill Hill, deputy associate administrator of NASA’s Exploration Systems Development Division, in a NASA statement.

Blastoff of the NASA’s first SLS heavy lift booster (SLS-1) carrying an unmanned test version of NASA’s Orion crew capsule is targeted for no later than November 2018.

Indeed the SLS will be the most powerful rocket the world has ever seen starting with its first liftoff. It will propel our astronauts on journey’s further into space than ever before.

SLS is “the first vehicle designed to meet the challenges of the journey to Mars and the first exploration class rocket since the Saturn V.”

Crews seated inside NASA’s Orion crew module bolted atop the SLS will rocket to deep space destinations including the Moon, asteroids and eventually the Red Planet.

“There have been challenges, and there will be more ahead, but this review gives us confidence that we are on the right track for the first flight of SLS and using it to extend permanent human presence into deep space,” Hill stated.

The core stage (first stage) of the SLS will be powered by four RS-25 engines and a pair of five-segment solid rocket boosters (SRBs) that will generate a combined 8.4 million pounds of liftoff thrust in its inaugural Block 1 configuration, with a minimum 70-metric-ton (77-ton) lift capability.

Overall the SLS Block 1 configuration will be some 10 percent more powerful than the Saturn V rockets that propelled astronauts to the Moon, including Neil Armstrong, the first human to walk on the Moon during Apollo 11 in July 1969.

The SLS core stage is derived from the huge External Tank (ET) that fueled NASA Space Shuttle’s for three decades. It is a longer version of the Shuttle ET.

NASA initially planned to paint the SLS core stage white, thereby making it resemble the Saturn V.

But since the natural manufacturing color of its insulation during fabrication is burnt orange, managers decided to keep it so and delete the white paint job.

“As part of the CDR, the program concluded the core stage of the rocket and Launch Vehicle Stage Adapter will remain orange, the natural color of the insulation that will cover those elements, instead of painted white,” said NASA.

There is good reason to scrap the white color motif because roughly 1000 pounds of paint can be saved by leaving the tank with its natural orange pigment.

This translates directly into another 1000 pounds of payload carrying capability to orbit.

“Not applying the paint will reduce the vehicle mass by potentially as much as 1,000 pounds, resulting in an increase in payload capacity, and additionally streamlines production processes,” Shannon Ridinger, NASA Public Affairs spokeswomen told Universe Today.

After the first two shuttle launches back in 1981, the ETs were also not painted white for the same reason – in order to carry more cargo to orbit.

“This is similar to what was done for the external tank for the space shuttle. The space shuttle was originally painted white for the first two flights and later a technical study found painting to be unnecessary,” Ridinger explained.

NASA said that the CDR was completed by the SLS team in July and the results were also further reviewed over several more months by a panel of outside experts and additionally by top NASA managers.

“The SLS Program completed the review in July, in conjunction with a separate review by the Standing Review Board, which is composed of seasoned experts from NASA and industry who are independent of the program. Throughout the course of 11 weeks, 13 teams – made up of senior engineers and aerospace experts across the agency and industry – reviewed more than 1,000 SLS documents and more than 150 GB of data as part of the comprehensive assessment process at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, where SLS is managed for the agency.”

“The Standing Review Board reviewed and assessed the program’s readiness and confirmed the technical effort is on track to complete system development and meet performance requirements on budget and on schedule.”

The final step of the SLS CDR was completed this month with another extremely thorough assessment by NASA’s Agency Program Management Council, led by NASA Associate Administrator Robert Lightfoot.

“This is a major step in the design and readiness of SLS,” said John Honeycutt, SLS program manager.

The CDR was the last of four reviews that examine SLS concepts and designs.

NASA says the next step “is design certification, which will take place in 2017 after manufacturing, integration and testing is complete. The design certification will compare the actual final product to the rocket’s design. The final review, the flight readiness review, will take place just prior to the 2018 flight readiness date.”

“Our team has worked extremely hard, and we are moving forward with building this rocket. We are qualifying hardware, building structural test articles, and making real progress,” Honeycutt elaborated.

Numerous individual components of the SLS core stage have already been built and their manufacture was part of the CDR assessment.

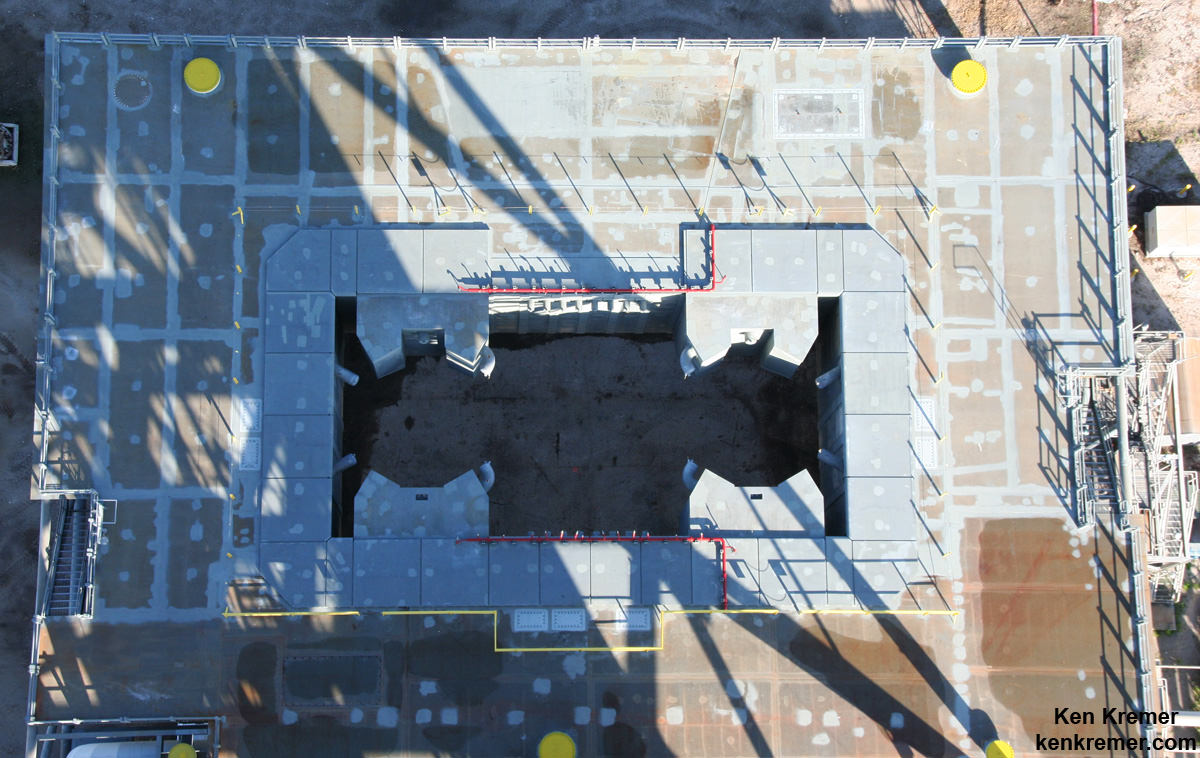

The SLS core stage is being built at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans. It stretches over 200 feet tall and is 27.6 feet in diameter and will carry cryogenic liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen fuel for the rocket’s four RS-25 engines.

On Sept. 12, 2014, NASA Administrator Charles Bolden officially unveiled the world’s largest welder at Michoud, that will be used to construct the core stage, as I reported earlier during my on-site visit – here.

The first stage RS-25 engines have also completed their first round of hot firing tests. And the five segment solid rocket boosters has also been hot fired.

NASA decided that the SRBs will be painted with something like racing stripes.

“Stripes will be painted on the SRBs and we are still identifying the best process for putting them on the boosters; we have multiple options that have minimal impact to cost and payload capability, ” Ridinger stated.

With the successful completion of the CDR, the components of the first core stage can now proceed to assembly of the finished product and testing of the RS-25 engines and boosters can continue.

“We’ve successfully completed the first round of testing of the rocket’s engines and boosters, and all the major components for the first flight are now in production,” Hill explained.

NASA plans to gradually upgrade the SLS to achieve an unprecedented lift capability of 130 metric tons (143 tons), enabling the more distant missions even farther into our solar system.

The first SLS test flight with the uncrewed Orion is called Exploration Mission-1 (EM-1) and will launch from Launch Complex 39-B at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC).

The SLS/Orion stack will roll out to pad 39B atop the Mobile Launcher now under construction – as detailed in my recent story and during visit around and to the top of the ML at KSC.

Orion’s inaugural mission dubbed Exploration Flight Test-1 (EFT) was successfully launched on a flawless flight on Dec. 5, 2014 atop a United Launch Alliance Delta IV Heavy rocket Space Launch Complex 37 (SLC-37) at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and Planetary science and human spaceflight news.