Video Caption: Last moments of Orion descent as viewed from the recovery ship USS Anchorage. Credit: NASA/US Navy

Relive the final moments of the first test flight of NASA’s Orion spacecraft on Dec. 5, 2014, through this amazing series of up close videos showing the spacecraft plummeting back to Earth through the rollicking ocean recovery by dive teams from the US Navy and the USS Anchorage amphibious ship.

The two orbit, 4.5 hour flight maiden test flight of Orion on the Exploration Flight Test-1 (EFT-1) mission was a complete success.

It was brought back to land to the US Naval Base San Diego, California.

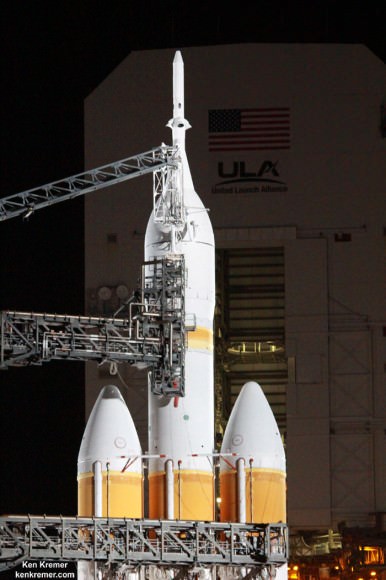

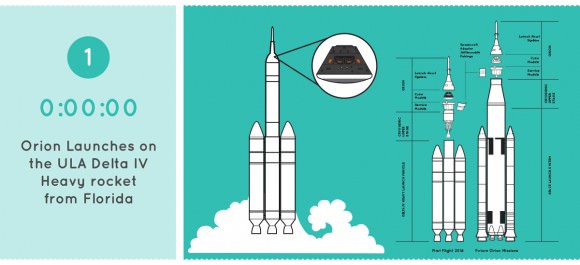

Orion’s test flight began with a flawless launch on Dec. 5 as it roared to orbit atop the fiery fury of a 242 foot tall United Launch Alliance Delta IV Heavy rocket – the world’s most powerful booster – at 7:05 a.m. EST from Space Launch Complex 37 (SLC-37) at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida.

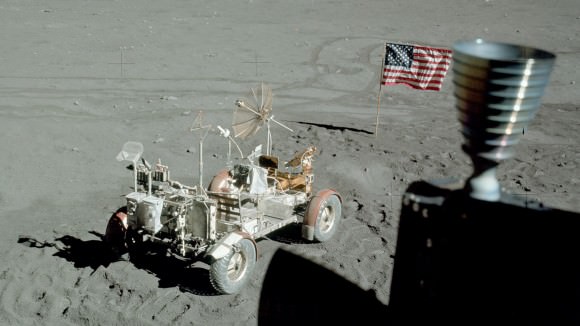

The unpiloted test flight of Orion on the EFT-1 mission ignited NASA’s roadmap to send Humans to Mars by the 2030s by carrying the capsule farther away from Earth than any spacecraft designed for astronauts has traveled in more than four decades.

Humans have not ventured beyond low Earth orbit since the launch of Apollo 17 on NASA’s final moon landing mission on Dec. 7, 1972.

Video Caption: NASA TV covers the final moments of Orion spacecraft descent and splashdown in the Pacific Ocean approximately 600 miles southwest of San Diego on Dec. 5, 2014, as viewed live from the Ikhana airborne drone. Credit: NASA TV

The spacecraft was loaded with over 1200 sensors to collect critical performance data from numerous systems throughout the mission for evaluation by engineers.

EFT-1 tested the rocket, second stage, and jettison mechanisms as well as avionics, attitude control, computers, environmental controls, and electronic systems inside the Orion spacecraft and ocean recovery operations.

It also tested the effects of intense radiation by traveling twice through the Van Allen radiation belt.

After successfully accomplishing all its orbital flight test objectives, the capsule fired its thrusters and began the rapid fire 10 minute plummet back to Earth.

During the high speed atmospheric reentry, it approached speeds of 20,000 mph (32,000 kph), approximating 85% of the reentry velocity for astronauts returning from voyages to the Red Planet.

The capsule endured scorching temperatures near 4,000 degrees Fahrenheit in a critical and successful test of the 16.5-foot-wide heat shield and thermal protection tiles.

The entire system of reentry hardware, commands, and 11 drogue and main parachutes performed flawlessly.

Finally, Orion descended on a trio of massive red and white main parachutes to achieve a statistical bulls-eye splashdown in the Pacific Ocean, 600 miles southwest of San Diego, at 11:29 a.m. EST.

It splashed down within one mile of the touchdown spot predicted by mission controllers after returning from an altitude of over 3600 miles above Earth.

The three main parachutes slowed Orion to about 17 mph (27 kph).

Here’s a magnificent up close and personal view direct from the US Navy teams that recovered Orion on Dec. 5, 2014.

Video Caption: Just released footage of the Orion Spacecraft landing and recovery! See all the sights and sounds, gurgling, and more from onboard the Zodiac boats with the dive teams on Dec. 5, 2014. See the initial recovery operations, including safing the crew module and towing it into the well deck of the USS Anchorage, a landing platform-dock ship. Credit: US Navy

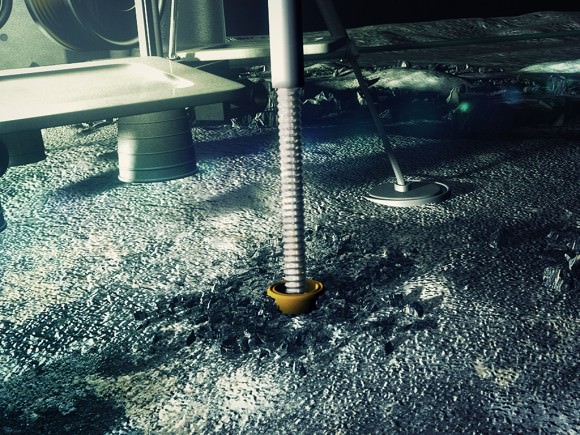

Navy teams in Zodiac boats had attached a collar and winch line to Orion at sea and then safely towed it into the flooded well deck of the USS Anchorage and positioned it over rubber “speed bumps.”

Next they secured Orion inside its recovery cradle and transported it back to US Naval Base San Diego where it was off-loaded from the USS Anchorage.

The Orion EFT-1 spacecraft was recovered by a combined team from NASA, the U.S. Navy, and Orion prime contractor Lockheed Martin.

Orion has been offloaded from the USS Anchorage and moved about a mile to the “Mole Pier” where Lockheed Martin technicians have conducted the first test inspection of the crew module and collected test data.

It will soon be hauled on a flatbed truck across the US for a nearly two week trip back to Kennedy where it will arrive just in time for the Christmas holidays.

Technicians at KSC will examine every nook and cranny of Orion and will dissemble it for up close inspection and lessons learned.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and planetary science and human spaceflight news.