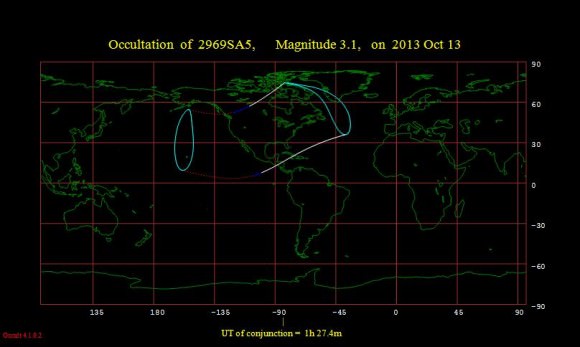

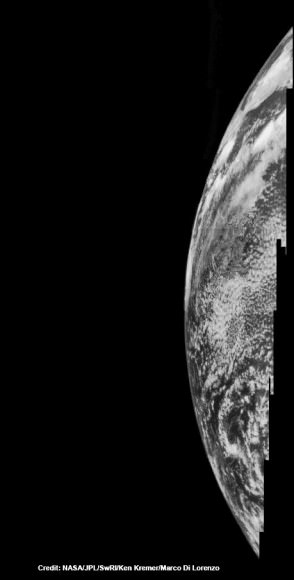

Juno swoops over Argentina

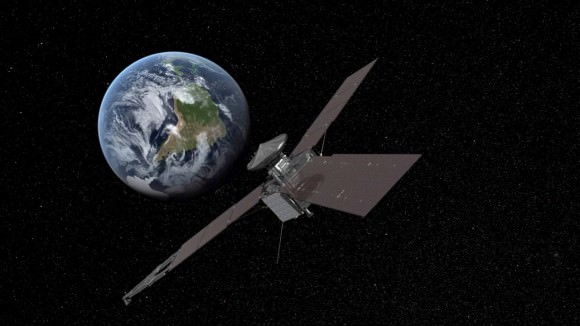

This reconstructed day side image of Earth is one of the 1st snapshots transmitted back home by NASA’s Jupiter-bound Juno spacecraft during its speed boosting flyby on Oct. 9, 2013. It was taken by the probes Junocam imager and methane filter at 12:06:30 PDT and an exposure time of 3.2 milliseconds. Juno was flying over South America and the southern Atlantic Ocean. The coastline of Argentina is visible at top right. Credit: NASA/JPL/SwRI/MSSS/Ken Kremer

See another cool Junocam image below[/caption]

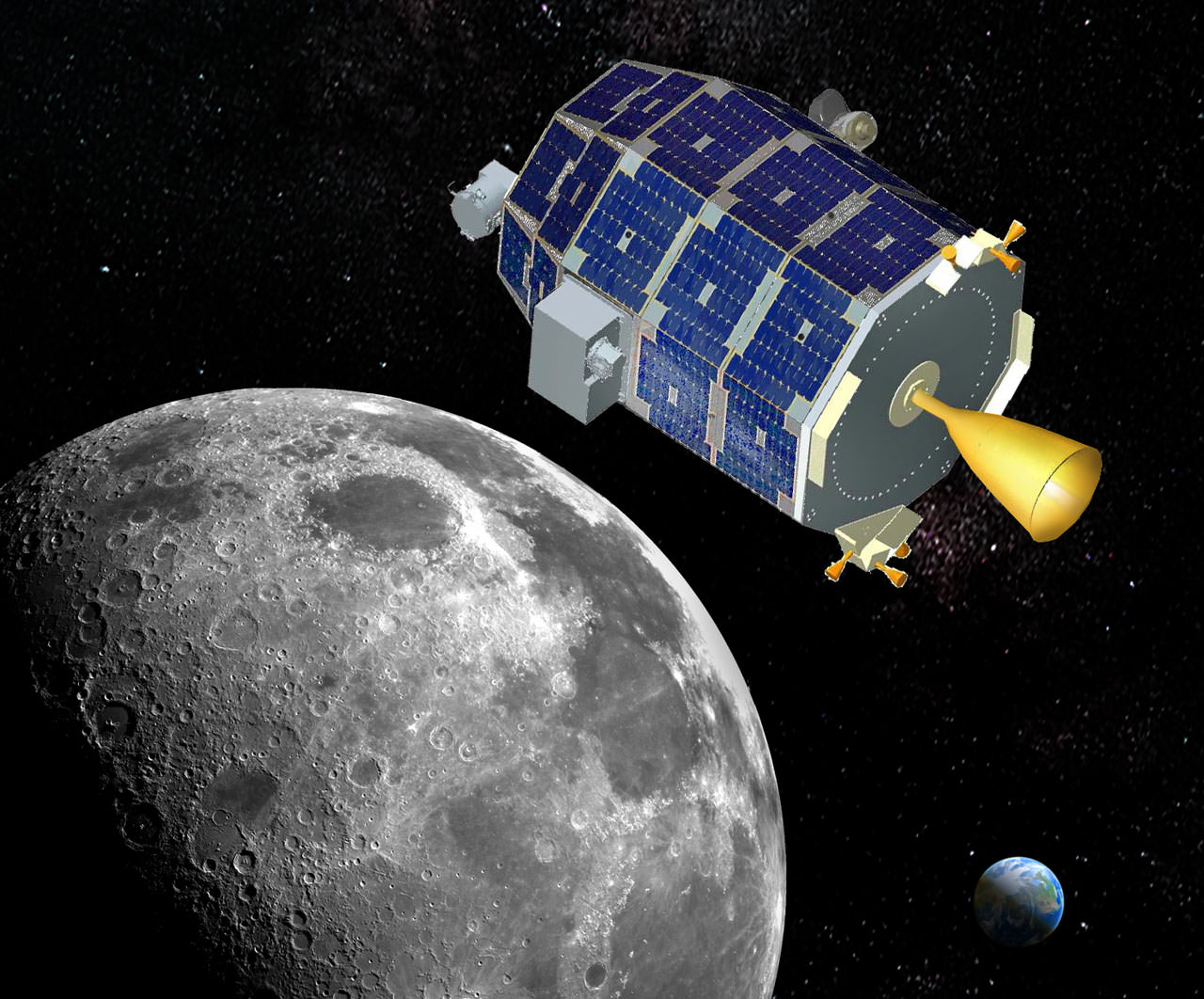

Engineers have deftly managed to successfully restore NASA’s Jupiter-bound Juno probe back to full operation following an unexpected glitch that placed the ship into ‘safe mode’ during the speed boosting swing-by of Earth on Wednesday, Oct. 9 – the mission’s top scientist told Universe Today late Friday.

“Juno came out of safe mode today!” Juno principal investigator Scott Bolton happily told me Friday evening. Bolton is from the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), San Antonio, Texas.

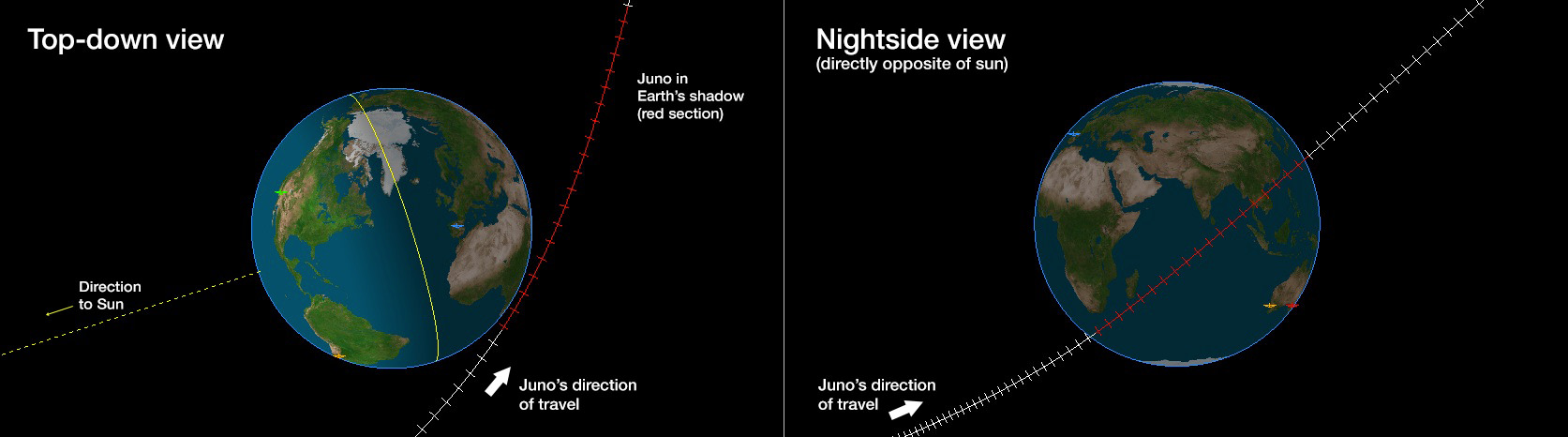

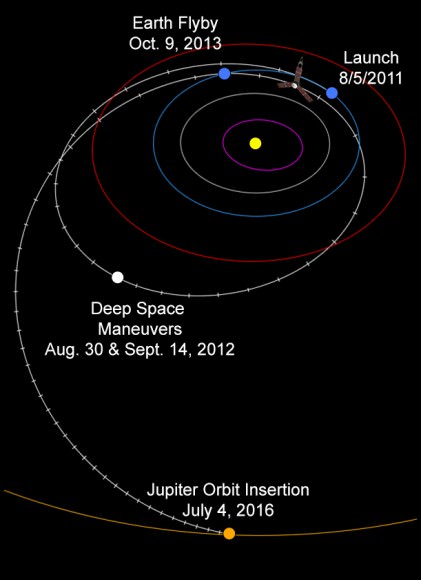

The solar powered Juno spacecraft conducted a crucial slingshot maneuver by Earth on Wednesday that accelerated its velocity by 16,330 mph (26,280 km/h) thereby enabling it to be captured into polar orbit about Jupiter on July 4, 2016.

“The safe mode did not impact the spacecraft’s trajectory one smidgeon!”

Juno exited safe mode at 5:12 p.m. ET Friday, according to a statement from the Southwest Research Institute. Safe mode is a designated fault protective state that is preprogrammed into spacecraft software in case something goes amiss.

“The spacecraft is currently operating nominally and all systems are fully functional,” said the SwRI statement.

Although the Earth flyby did accomplish its primary goal of precisely targeting Juno towards Jupiter – within 2 kilometers of the aim point ! – the ship also suffered an unexplained anomaly that placed Juno into ‘safe mode’ at some point during the swoop past Earth.

“After Juno passed the period of Earth flyby closest approach at 12:21 PM PST [3:21 PM EDT] and we established communications 25 minutes later, we were in safe mode,” Juno Project manager Rick Nybakken, told me in a phone interview soon after Wednesday’s flyby of Earth. Nybakken is from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena, CA.

Nybakken also said that the probe was “power positive and we have full command ability.”

So the mission operations teams at JPL and prime contractor Lockheed Martin were optimistic about resolving the safe mode issue right from the outset.

“The spacecraft acted as expected during the transition into and while in safe mode,” acording to SwRI.

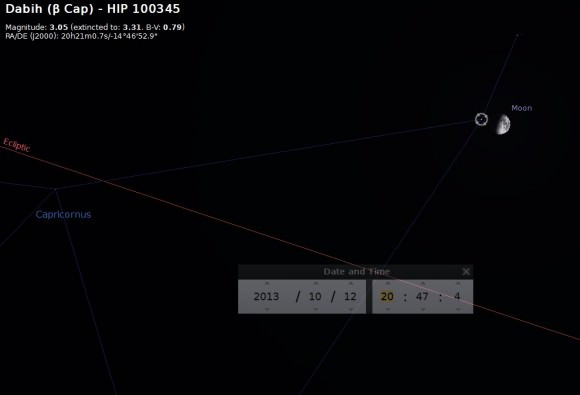

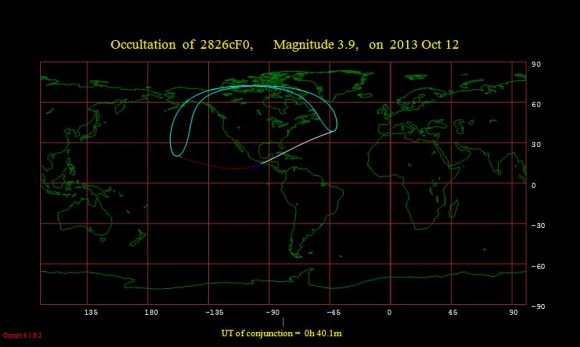

During the flyby, the science team also planned to observe Earth using most of Juno’s nine science instruments since the slingshot also serves as an important dress rehearsal and key test of the spacecraft’s instruments, systems and flight operations teams.

“The Juno science team is continuing to analyze data acquired by the spacecraft’s science instruments during the flyby. Most data and images were downlinked prior to the safe mode event.”

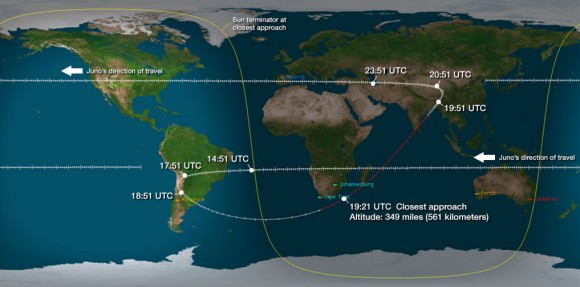

Juno’s closest approach took place over the ocean just off the tip of South Africa at about 561 kilometers (349 miles).

Juno launched atop an Atlas V rocket two years ago from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, FL, on Aug. 5, 2011 on a journey to discover the genesis of Jupiter hidden deep inside the planet’s interior.

The $1.1 Billion Juno probe is continuing on its 2.8 Billion kilometer (1.7 Billion mile) outbound trek to the Jovian system.

During a one year long science mission – entailing 33 orbits lasting 11 days each – the probe will plunge to within about 3000 miles of the turbulent cloud tops and collect unprecedented new data that will unveil the hidden inner secrets of Jupiter’s origin and evolution.

“Jupiter is the Rosetta Stone of our solar system,” says Bolton. “It is by far the oldest planet, contains more material than all the other planets, asteroids and comets combined and carries deep inside it the story of not only the solar system but of us. Juno is going there as our emissary — to interpret what Jupiter has to say.”

Read more about Juno’s flyby in my articles – at NBC News; here, and Universe Today; here, here and here