[/caption]

Greetings, fellow SkyWatchers! Are you ready for another week filled with bright planets, a meteor shower, challenging lunar features, interesting stars and astronomy history? Then you have come to the right place! Bring along your telescopes and binoculars and meet me in the backyard…

Monday, April 30 – Karl Frederich Gauss was born on this day in 1777. Known as the “Prince of Mathematics,” Gauss contributed to the field of astronomy in many ways – from computing asteroid orbits to inventing the heliotrope. Out of Gauss’ many endeavors, he is most recognized for his work in magnetism. We understand the term “gauss” as a magnetic unit – a refrigerator magnet carries about 100 gauss while an average sunspot might go up to 4000. On the most extreme ends of the magnetic scale, the Earth produces about 0.5 gauss at its poles, while a magnetar can produce as much as 10 to the 15th power in gauss units!

While we cannot directly observe a magnetar, those living in the Southern Hemisphere can view a region of the sky where magnetars are known to exist – the Large Magellanic Cloud – or you can use the projection method to view a sunspot! If you have a proper solar filter, magnetism distorts sunspots as they near the limb – called the “Wilson Effect”

Tuesday, May 1 – On this day in 1949 Gerard Kuiper discovered Nereid, a satellite of Neptune. If you’re game, you can find Neptune – usually hanging around in Capricornus – about an hour before dawn. While it can be seen in binoculars as a bluish “star,” it takes around a 6″ telescope and some magnification to resolve its disc. Today’s imaging technology can even reveal its moons!

While you’re out this morning, keep an eye on the sky for the peak of the Phi Bootid meteor shower, whose radiant is near the constellation of Hercules. While the best time to view a meteor shower is around 2:00 a.m. local time, you will have best success watching for these meteors when the Moon is as far west as possible. The average fall rate is about 6 per hour.

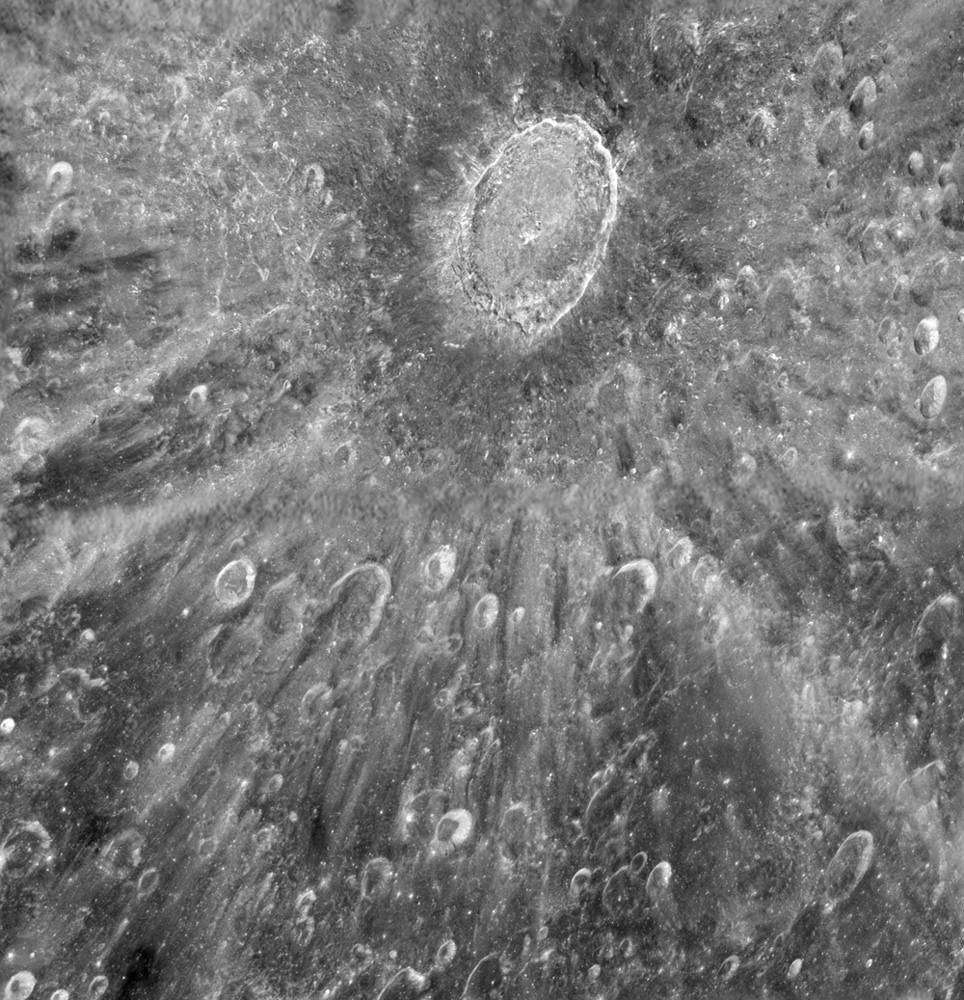

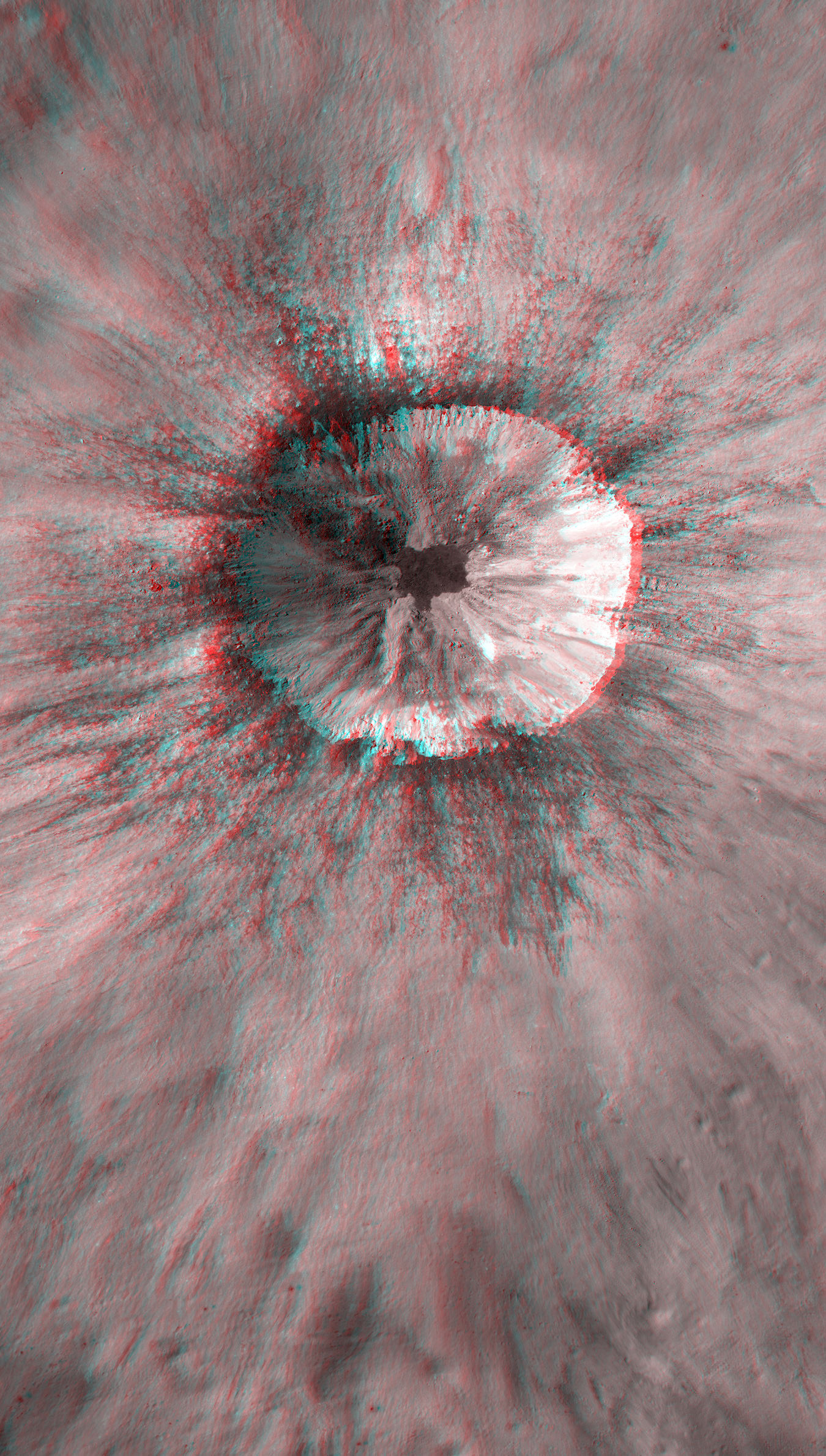

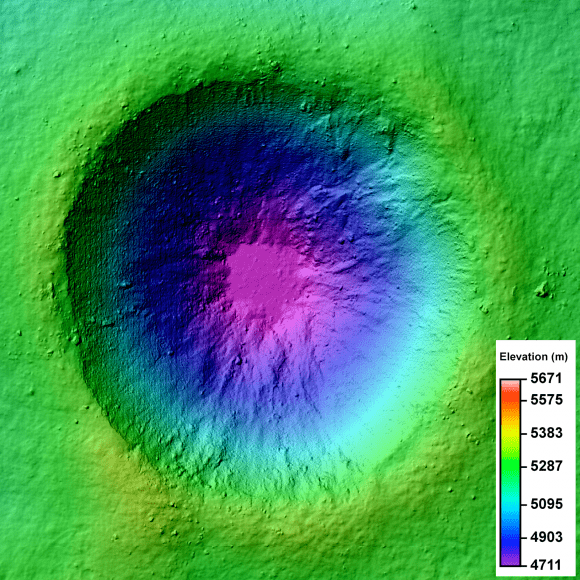

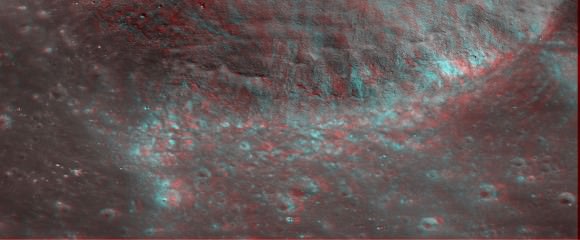

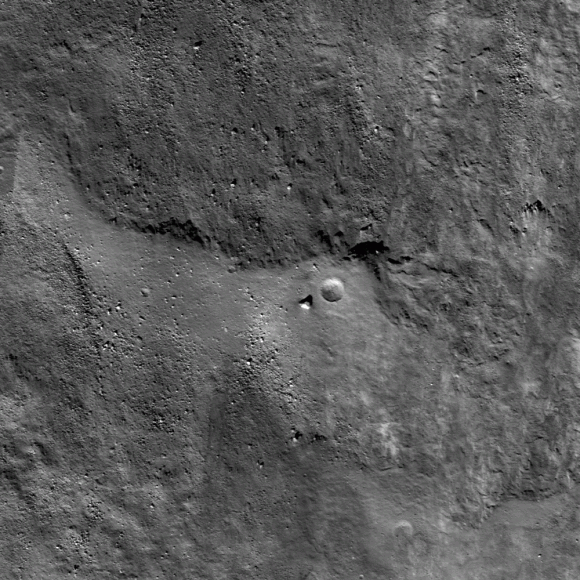

Our lunar mission for tonight is to move south, past the crater rings of Ptolemaeus, Alphonsus, Arzachel, and Purbach, until we end up at the spectacular crater Walter.

Named for Dutch astronomer Bernhard Walter, this 132- by 140-kilometer-wide lunar feature offers up amazing details at high power. It is worthwhile to take the time to study the differing levels, which drop to a maximum of 4,130 meters below the surface. Multiple interior strikes abound, but the most fascinating of all is the wall crater Nonius. Spanning 70 kilometers, Nonius would also appear to have a double strike of its own—one that’s 2,990 meters deep!

Wednesday, May 2 – On the lunar surface, we can enjoy a strange, thin feature. If you used last night’s map, you’re well acquainted with this area! Look toward the lunar south where you will note the prominent rings of craters Ptolemaeus, Alphonsus, Arzachel, Purbach, and Walter descending from north to south. Just west of them, you’ll see the emerging Mare Nubium. Between Purbach and Walter you will see the small, bright ring of Thebit with a crater caught on its edge. Look further west and you will see a long, thin, dark feature cutting across the mare. Its name? Rupes Recta – better known as The Straight Wall, or sometimes Rima Birt. It is one of the steepest known lunar slopes rising around 366 meters from the surface at a 41 degree angle.

Be sure to mark your lunar challenge notes and we’ll visit this feature again!

Another great target for a bright night is Delta Corvi. 125 light-years away, it displays a yellowish color primary and slightly blue secondary that’s an easily split star in any telescope, and a nice visual double with Eta in binoculars. Use low power and see if you can frame this bright grouping of stars in the same eyepiece field.

Before you put the telescope away for the evening, be sure to visit with Mars. If you’ve been keeping track, the red planet is slowly moving away from us and dimming even more. Tonight it should have reached an apparent -0.0 magnitude. Compare it to other nearby stars and gauge its brightness for yourself. How has its apparent position against the background stars changed over the weeks? Have you noted features like Syrtis Major or Amazonis Planitia? How have the polar caps changed?

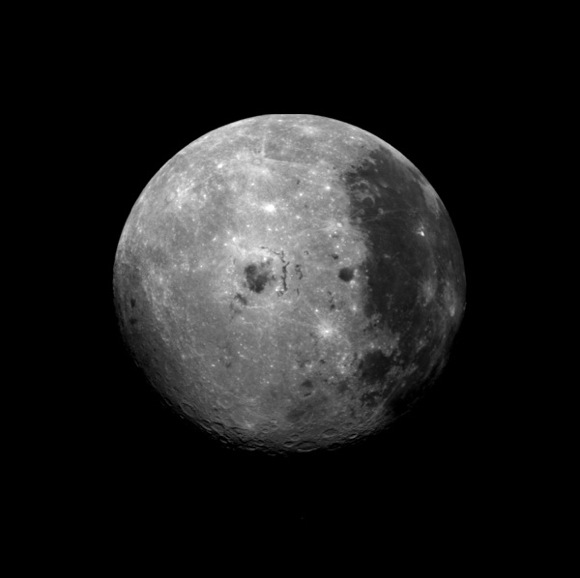

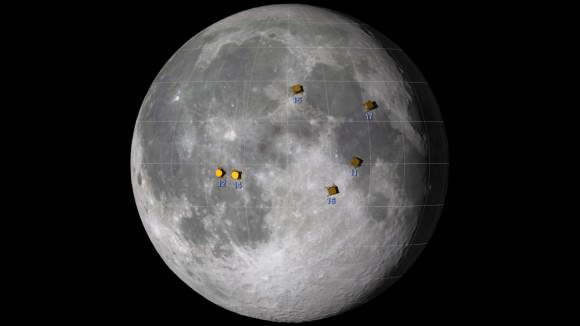

Thursday, May 3 – Tonight we’ll use what we learned previously to locate another unusual feature – Montes Recti or the “Straight Range.” You’ll find this curiosity tucked between Plato and Sinus Iridum on the north shore of Mare Imbrium.

To binoculars or small scopes at low power, this isolated strip of mountains will appear as a white line drawn across the grey mare. It is believed this feature may be all that is left of a crater wall from the Imbrium impact. It runs for a distance of around 90 kilometers, and is approximately 15 kilometers wide. The Straight Range and some of its peaks reach up to 2072 meters! Although this doesn’t sound particularly impressive, that’s over twice as tall as the Vosges Mountains in central western Europe, and on the average very comparable to the Appalachian Mountains in the eastern United States.

Friday, May 4 – Tonight you are on your own without a map. Lunar features are easy when you become acquainted with them! Return to the Moon and explore with binoculars or telescopes the area to the south around another easy and delightful lunar feature you should recognize, the crater Gassendi. At around 110 kilometers in diameter and 2010 meters deep, this ancient crater contains a triple mountain peak in its center. As one of the most “perfect circles” on the Moon, the south wall of Gassendi has been eroded by lava flows over a 48 kilometer expanse and offers a great amount of detail to telescopic observers on its ridge- and rille-covered floor. For those observing with binoculars? Gassendi’s bright ring stands on the north shore of Mare Humorum…an area about the size of the state of Arkansas!

Northeast of Regulus by about a fistwidth is 2.61 magnitude Gamma Leonis – also known as Algieba. This is one of the finest double stars in the sky, but a little difficult at low power since the pair is both bright and close. Separated by about twice the diameter of our own solar system, this 90 light-year distant pair is slowly widening.

Another two fingerwidths north is 3.44 magnitude Zeta Leonis – also named Aldhafera. Located about 130 light-years away, this excellent star has an optical companion which is viewable in binoculars – 35 Leonis. Remember this pair, because it will lead you to galaxies later!

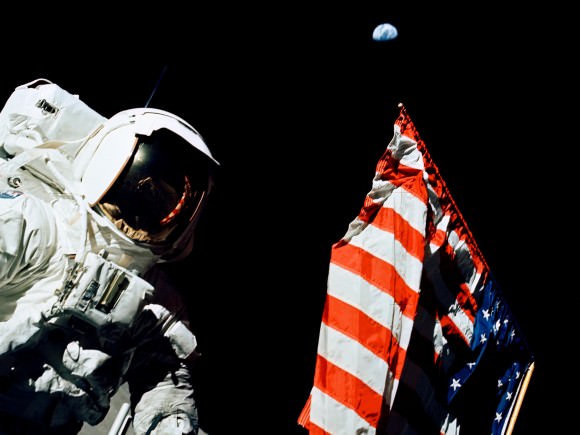

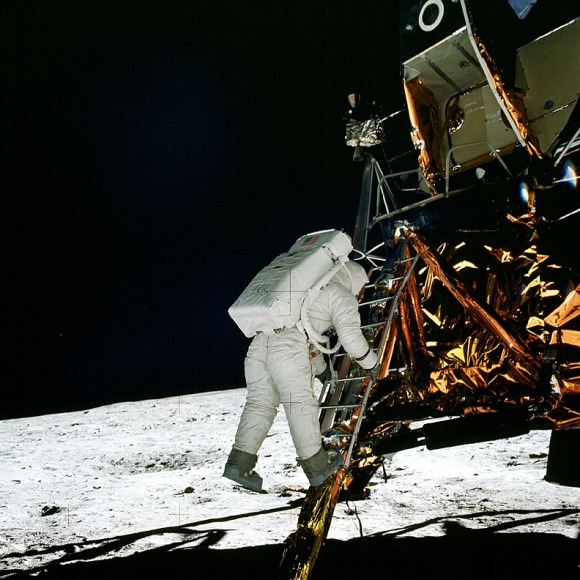

Saturday, May 5 – In 1961 Alan Shepard became the first American in “space” (as we now refer to that region above the sky), taking a 15 minute suborbital ride aboard the Mercury craft Freedom 7.

Return to the Moon tonight to have a look on the terminator near the southern cusp for two outstanding features. The easiest is crater Schickard – a class V mountain-walled plain that spans 227 kilometers. Named for German astronomer Wilhelm Schickard, this beautiful old crater with the subtle interior details has another crater caught on its northern wall named Lehmann.

Look further south for one of the Moon’s most incredible features – Wargentin. Among the many strange things on the lunar surface, Wargentin is unique. Once upon a time, it was a very normal crater and had been that way for hundreds of millions of years – then it happened. Either a fissure opened in its interior, or the meteoric impact that formed it caused molten lava to begin to rise. Oddly enough, Wargentin’s walls were without large enough breaks to allow the lava to escape and it continued to fill the crater to the rim. Often referred to as “the Cheese,” enjoy Wargentin tonight for its unusual appearance and be sure to note Nasmyth and Phocylides as well!

Before we leave, let’s have a look east at 3.34 magnitude Theta Leonis. Also known as Chort, mark this one in your memory, as well as 3.94 magnitude Iota to the south as markers for a galaxy hop. Last is easternmost 2.14 magnitude Beta. Denebola is the “Lion’s Tail” and has several faint optical companions.

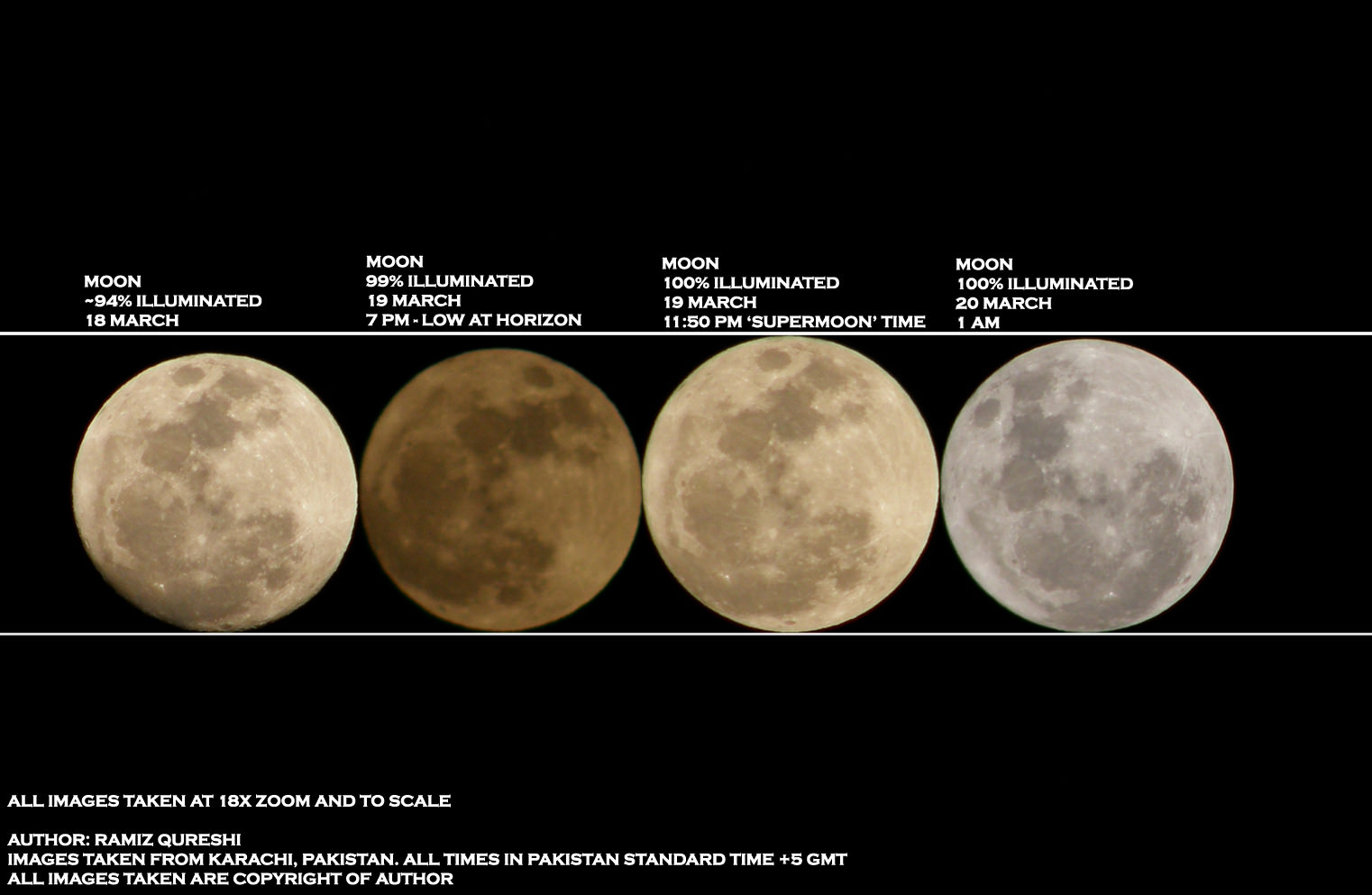

Sunday, May 6 – Earlier we learned about awesome magnetic energy, but what happens when you find magnetism in a very unlikely place? Tonight might be Full Moon, but we can still have a look at the lunar surface just a little southeast of the grey oval of Grimaldi. The area we are looking for is called the Sirsalis Rille and on an orb devoid of magnetic fields – it’s magnetic! Like a dry river bed, this ancient “crack” on the surface runs 480 kilometers along the surface and branches in many areas.

For those who like curiosities, our target for tonight will be 1.4 degrees northwest of 59 Leonis, which is itself about a degree southwest of Xi. While this type of observation may not be for everyone, what we are looking for is a very special star – a red dwarf named Wolf 359 (RA 10 56 28.99 Dec +07 00 52.0).

Discovered photographically by Max Wolf in 1959, charts from that time period will no longer be accurate because of the star’s large proper motion. It is one of the least luminous stars known, and we probably wouldn’t even know it was there except for the fact that it is the third closest star to our solar system. Located only 7.5 light-years away, this miniature star is about 8% the size of our Sun – making it roughly the size of Jupiter. Oddly enough, it is also a “flare star” – capable of jumping another magnitude brighter at random intervals. It might be faint and difficult to spot in mid-sized scopes, but Wolf 359 is definitely one of the most unusual things you will ever observe!

Until next week? Ask for the Moon, but keep on reaching for the stars!