[/caption]

When it comes to space flight, the media, politicians and the public tend to focus on who was “first.” Many point to the fact that the Soviet Union was first to send both a satellite and man into orbit as the impetus behind the U.S. into the new frontier. However, the “lasts” are often lost to history, forgotten in the dusty pages of some biographer’s notes. As the shuttle era closes, there are several lasts that, so far, have gone unmentioned. More importantly, the program, as a whole, has been an incredibly powerful engine for change – both within the U.S. and abroad.

Alvin Drew is the last African-American currently scheduled to fly in the shuttle program. Additionally, there is one other last that may or may not be highlighted (if NASA gets the necessary funding for the mission) – the last woman to fly in the shuttle program – Sandra “Sandy” Magnus on STS-135. Although NASA has declared STS-135 an official mission, the funding needed to fly it, has yet to be approved.

These two “lasts” may or may not be noted by the media, many of whom give the appearance of looking down on the program. The shuttle, as Bob Crippen once said is often “bad-mouthed” for not living up the expectations laid out at the beginning of the program. Perhaps, in time, the shuttle program will be remembered as what it was – an engine that worked to remove many social barriers. The shuttle era could, one day, be regarded as the program that opened space flight to people of all races and nations.

The number of nations that have flown astronauts onboard NASA’s fleet of shuttles is far more expansive than most think. Canada, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Switzerland, Israel, Japan, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia and the Ukraine have all flown astronauts aboard the space shuttle.

During the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo Programs the crews were universally white and male. With the shuttle’s capacity for larger crews – that dynamic changed. The U.S. flew its first woman, Sally Ride, in 1984 (the Soviet Union flew its first woman, Valentina Tereshkova in 1963) the first African-American, Guy Bluford also flew that year. After that the backgrounds of the astronauts who flew on the shuttle continued to diversify.

The first female pilot, Eileen Collins, flew on board STS-63 – she would go on to become the first female commander – and to return NASA to flight after the Columbia disaster on STS-114 in 2005. Charles Bolden, an African-American, commanded the first joint Russian/American shuttle mission (mission STS-61 on Discovery) and would go on to become the first African-American NASA administrator when he was selected in 2009. These are just two of numerous examples of how the shuttle has empowered different genders and races.

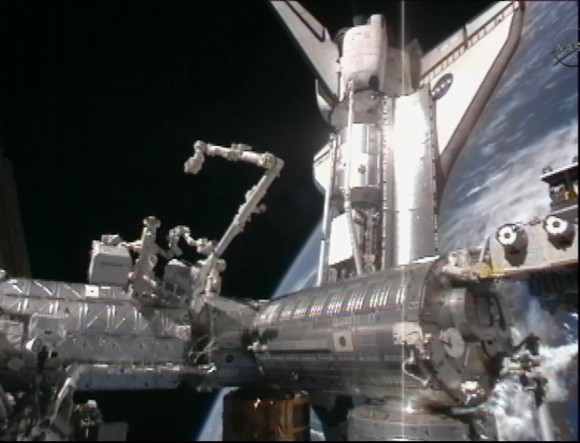

So while Drew’s and Magnus’ place in history may not be well remembered, those that paved the way for them as well as the shuttle’s capabilities made it all possible. Time will tell if the shuttle will be remembered for its shortcomings or if it will be remembered for allowing astronauts of all stripes to fly, for the Hubble Space Telescope to be deployed and serviced, for the International Space Station to be built and for all the other positive things that the shuttle made possible since it first flew in April of 1981.

“The shuttle has flown on such a routine basis for the past 30 years that many Americans may not realize the contributions it has made for all humankind,” said Candrea Thomas a NASA public affairs officer. “When the shuttles stop flying, I believe Americans will remember all the wonderful technologies and advancements that these amazing spacecraft, and the diverse group of people who worked on them, made possible.”