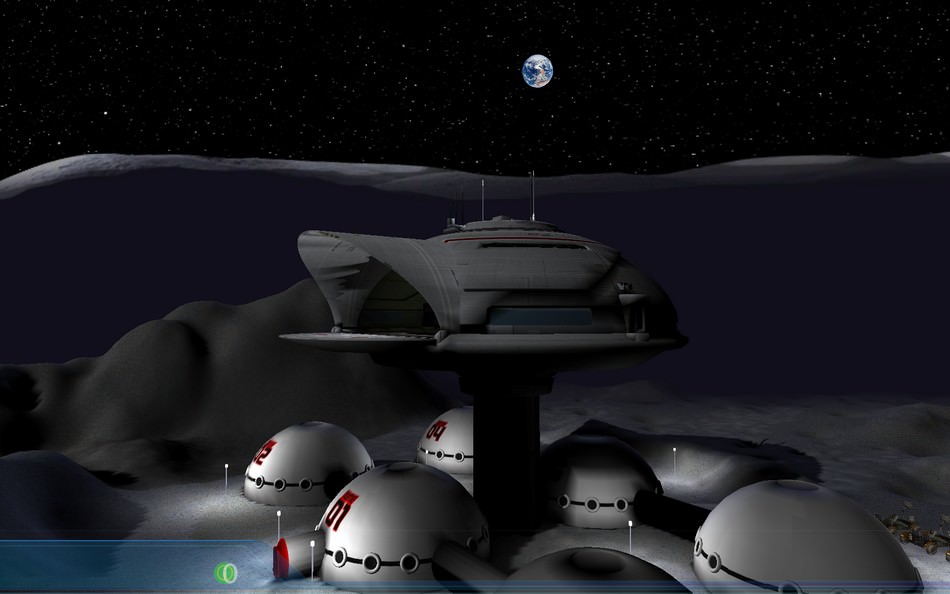

[/caption]In a budget blueprint released by the White House on Thursday, President Barack Obama has confirmed his intent to carry out the planned retirement of the ageing Space Shuttle next year. Additionally, the the blueprint affirms Obama’s stance on a return trip to the Moon. The US will return to the lunar surface by the year 2020, following the time scale set out by George W. Bush’s 2004 Vision for Space Exploration. However, there is no mention that the next manned lunar mission will be carried out by the Constellation Program, a project plagued by criticism about its design and technology.

Although the blueprint may differ from the final budget submitted to Congress in April, it looks like there is some certainty about the future of the shuttle and the direction NASA will be taking over the next decade. And now the space agency has a little bit more money to do something about that troublesome 5-year gap in US manned access to space…

So, any hope to extend the life of the Shuttle looks to have been dashed. Although there could still be a chance for a shuttle extension when the final budget is submitted, it seems as if President Obama has made his intent very clear; the 25 year-old space launch system will be mothballed, as planned, in 2010. This may come as a relief to many as extending the operational lifetime of the shuttle could be a safety risk, however, many on Florida’s Space Coast won’t be so happy as they could be looking at losing their jobs sooner than they would have hoped.

Generally, these decisions have been welcomed, including the extra $2.4 billion NASA will receive for the 2010 fiscal year (when compared with 2008):

Combined with $1 billion provided to NASA in the $787 billion stimulus package signed into law Feb. 17, the agency would receive $2 billion more than in the $17.7 billion 2009 NASA budget that was passed by the House – an increase that equals an Obama campaign promise. — Florida Today

It remains uncertain how the gap between shuttle retirement and Constellation launch could be shortened from the minimum of five years, but the extra cash is bound to boost confidence. But where does the blueprint say Constellation is even part of the plan? It doesn’t, sparking some media sources to point out that it remains a possibility that the Ares rocket system could be abandoned in favour of making the existing Atlas V or Delta IV rockets human rated. However, space policy specialists are advising not to read too much into the omission.

“The budget doesn’t say a whole lot about any specific system,” said John Logsdon, a space policy analyst at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC. “I wouldn’t interpret the absence of the words ‘Constellation’, ‘Ares’, and ‘Orion’ one way or another. That’s really up to the the new management team, when it gets there.”

After all, since the departure of Michael Griffin as NASA Administrator, the space agency has been without a leader. Acting NASA Administrator Christopher Scolese is currently at the helm, saying that the new budget “is fiscally responsible and reflects the administration’s desire for a robust and innovative agency.” Unfortunately the details about the use of Constellation may remain sketchy until the final budget is submitted.

This may be the case, but President Obama has obviously seen the merit in the original plans to get man back to the Moon by the year 2020, despite criticism from a guy who has actually stood on the Moon, Buzz Aldrin. In an “alternative” proposal for the future of NASA, Aldrin and two co-authors posted a draft of the “Unified Space Vision” on the National Space Society’s website this week (Update: the draft has now been “Removed At Request of the Authors”), urging the administration not to mount an unnecessary lunar mission (been there, done that) and go straight for manned exploration of the asteroids and Mars. The Unified Space Vision, unfortunately, was probably too hard on NASA’s accomplishments, saying that “post-Apollo NASA” has become a “visionless jobs-providing enterprise that achieves little or nothing,” in developing a viable space transportation system. Many of the points raised are valid (and occasionally very tough), but would require a complete change in NASA’s structure to accomplish. I doubt we’ll see any radical changes being enacted any time soon.

So, we now have a pretty good idea as to what’s going to happen to the shuttle next year; it looks like the plan to get the US back to the Moon by 2020 is still on and NASA has been given an extra $2 billion to play with. I hope they spend it wisely, perhaps on private space launch contracts?

Sources: Florida Today, New Scientist