[/caption]It reads like the annual progress report from my first year in university. He lacks direction, he’s not motivated and he has filled his time with extra-curricular activities, causing a lack of concentration in lectures. However, it shouldn’t read like an 18 year-old’s passage through the first year of freedom; it should read like a successful, optimistic and inspirational prediction about NASA’s future in space.

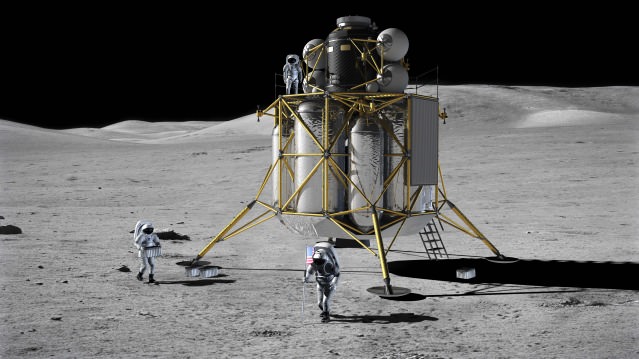

What am I referring to? It turns out that the Houston university where President John F. Kennedy gave his historic “We go to the Moon” speech back in 1962 has commissioned a report, recommending that NASA should give up its quest for returning to the Moon and focus more on environmental and energy projects. The reactions of several astronauts from the Mercury, Apollo and Shuttle eras have now been published. The conclusions in the Rice University report may have been controversial, but the reactions of the six ex-astronauts went well beyond that. They summed up the concern and frustration they feel for a space agency they once risked their lives for.

At the end of the day, it all comes down to how we interpret the importance of space exploration. Is it an unnecessary expense, or is it part of scientific endeavour where the technological spin-offs are more important than we think?

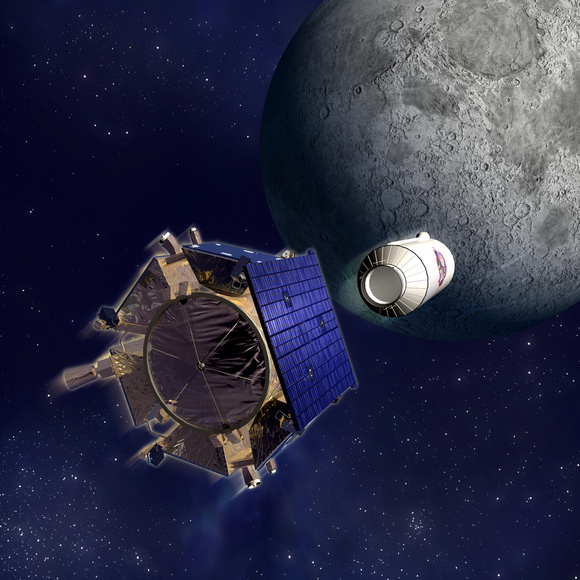

It is widely accepted that NASA is underfunded, mismanaged and falling short of its promises. Many would argue that this is a symptom of an old cumbersome government department that has lost its way. This could be down to institutional failings, lack of investment or loss of vision, but the situation is getting worse for NASA. Regardless, something isn’t right and now we are faced with a five year gap in US manned spaceflight capability, forcing NASA to buy Russian Soyuz flights. The Shuttle replacement, the Constellation Program, has even been written off by many before it has even carried out the first test launch.

So, from their unique perspective, what do these retired astronauts think of the situation? It turns out that some agree with the report, others are strongly opposed to it, whereas all voice concern for the future of NASA.

Four-time Shuttle astronaut Kathryn Thornton, agrees that the agency is underfunded and overstretched and dubious about the Institute’s recommendation that NASA should focus all its attention on environmental issues for four years. “I find it hard to believe we would be finished with the energy and environment issues in four years. If you talk about a re-direction, I think you talk about a permanent re-direction,” Thornton added.

Gene Cernan, commander of the 1972 Apollo 17 mission, believes that space exploration is essential to inspire the young and invigorate the educational system. He is shocked by the Institute’s recommendation to pull back on space exploration. The 74 year old was the last human to walk on the Moon and he believes NASA shouldn’t be focused on ways to save the planet, other agencies and businesses can do that.

“It just blows my mind what they would do to an organization like NASA that was designed and built to explore the unknown.” — Gene Cernan

Sally Ride, 57, a physicist and the first American woman to fly into space believes the risky option of extending the life of the Shuttle should be considered to allow US manned access to the space station to continue. The greater risk of being frozen out of the outpost simply is not an option. However, she advocates the report’s suggestion that NASA should also focus on finding solutions to climate change. “It will take us awhile to dig ourselves out,” she said. “But the long-term challenge we have is solving the predicament we have put ourselves in with energy and the environment.”

Franklin Chang Diaz, who shares world’s record for the most spaceflights (seven), believes that NASA has been given a very bad deal. He agrees with many of the report’s recommendations, not because the space agency should turn its back on space exploration, it’s because the agency has been put in an impossible situation.

“NASA has moved away from being at the edge of high tech and innovation,” said Chang Diaz. “That’s a predicament NASA has found itself in because it had to carry out a mission to return humans to the moon by a certain time (2020) and within a budget ($17.3 billion for 2008). It’s not possible.”

In Conclusion

This discussion reminds me of a recent debate not about space exploration, but another science and engineering endeavour here on Earth. The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) has its critics who will argue that this $5 billion piece of kit is not worth the effort, where the money spent on accelerating particles could be better spent on finding solutions for climate change, or a cure for cancer.

Prof. Cox explained that the science behind the LHC is “part of a journey” where the technological spin-offs and the knowledge gained from such a complex experiment cannot be predicted before embarking on scientific endeavour. Indeed, advanced medical technologies are being developed as a result of LHC research; the Internet may be revolutionized by new techniques being derived from work at the LHC; even the cooling system for the LHC accelerator electromagnets can be adapted for use in fusion reactors.

The point is that we may never fully comprehend what technologies, science or knowledge we may gain from huge experiments such as the LHC, and we certainly don’t know what spin-offs we can derive from continued advancement of space travel technology. Space exploration can only enhance our knowledge and scientific understanding.

If NASA starts pulling back on endeavours in space, taking a more introverted view of finding specific solutions to particular problems (such as finding a solution to climate change at the detriment to space exploration, as suggested by the Rice University report), we may never fully realise our potential as a race, and many of the problems here on Earth will never be solved…

Sources: Chron.com, Astroengine.com