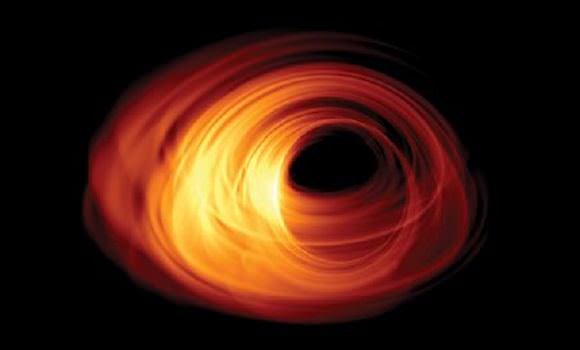

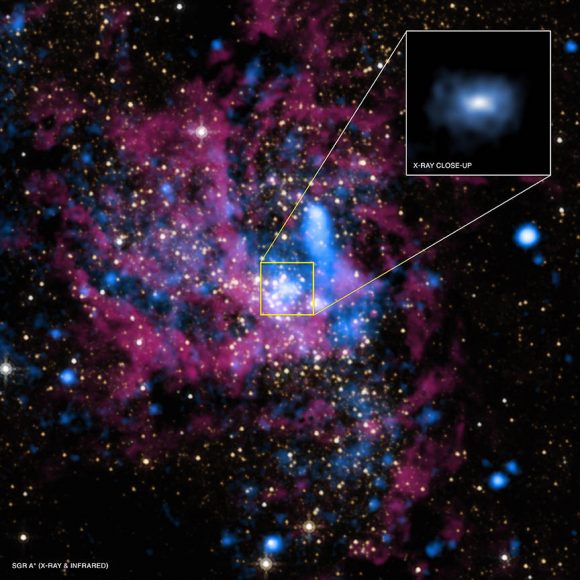

For decades, scientists have held that Supermassive Black Holes (SMBHs) reside at the center of larger galaxies. These reality-bending points in space exert an extremely powerful influence on all things that surround them, consuming matter and spitting out a tremendous amount of energy. But given their nature, all attempts to study them have been confined to indirect methods.

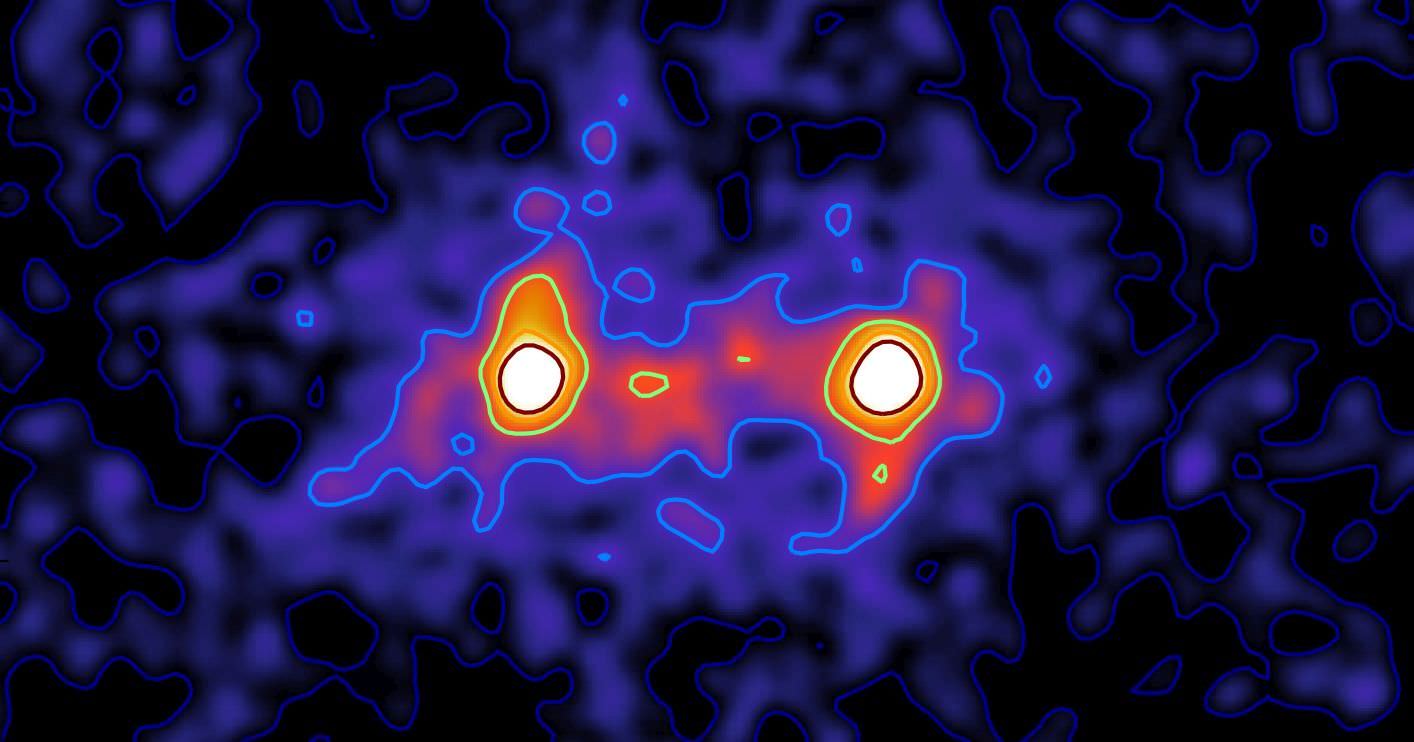

All of that changed beginning on Wednesday, April 12th, 2017, when an international team of astronomers obtained the first-ever image of a Sagittarius A*. Using a series of telescopes from around the globe – collectively known as the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) – they were able to visualize the mysterious region around this giant black hole from which matter and energy cannot escape – i.e. the event horizon.

Not only is this the first time that this mysterious region around a black hole has been imaged, it is also the most extreme test of Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity ever attempted. It also represents the culmination of the EHT project, which was established specifically for the purpose of studying black holes directly and improving our understanding of them.

Since it began capturing data in 2006, the EHT has been dedicated to the study of Sagittarius A* since it is the nearest SMBH in the known Universe – located about 25,000 light years from Earth. Specifically, scientists hoped to determine if black holes are surrounded by a circular region from which matter and energy cannot escape (which is predicted by General Relativity), and how they accrete matter onto themselves.

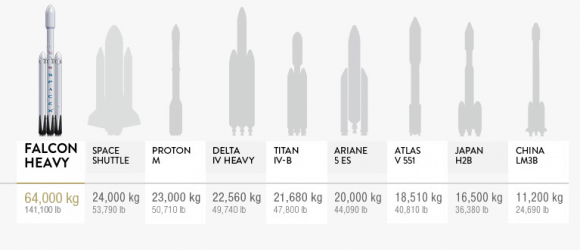

Rather than constituting a single facility, the EHT relies on a worldwide network of radio astronomy facilities based on four continents, all of which are dedicated to studying one of the most powerful and mysterious forces in the Universe. This process, whereby widely-space radio dishes from across the globe are connected into an Earth-sized virtual telescope, is known as Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI).

As Michael Bremer – an astronomer at the International Research Institute for Radio Astronomy (IRAM) and a project manager for the Event Horizon Telescope – said in an interview with AFP:

“Instead of building a telescope so big that it would probably collapse under its own weight, we combined eight observatories like the pieces of a giant mirror. This gave us a virtual telescope as big as Earth—about 10,000 kilometers (6,200 miles) is diameter.”

All told, the network includes instruments like the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, the Arizona Radio Observatory Submillimeter Telescope, the IRAM 30-meter Telescope in Spain, the Large Millimeter Telescope Alfonso Serrano in Mexico, the South Pole Telescope in Antarctica, and the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope and Submillimeter Array at Mauna Kea, Hawaii.

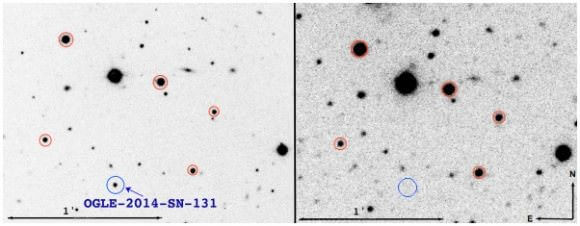

With these arrays, the EHT radio-dish network is the only one powerful enough to detect the light released when an object would disappear into Sagittarius A*. And from six nights – from Wednesday, April 5th, to Tuesday, April 11th, – all of its arrays were trained on the center of our Milky Way to do just that. By the end of the run, the international team announced that they had snapped the first-ever picture of an event horizon.

In the end, some 500 terabytes of data were collected. This data is now being transferred to the MIT Haystack Observatory in Massachusetts, where it will be processed by supercomputers and turned into an image. “For the first time in our history, we have the technological capacity to observe black holes in detail,” said Bremer. “The images will emerge as we combine all the data. But we’re going to have to wait several months for the result.”

Part of the reason for the wait is the fact that the recorded data obtained by the South Pole Telescope can only be collected when spring starts in Antarctica – which won’t happen until October 2017 at the earliest. As such, it won’t be until 2018 before the public gets to feast its eyes on the shadow region that surrounds Sagittarius A*, and it is not expected that the first image will be entirely clear.

As Heino Falcke – an astronomers from Radbound University who now chairs the Scientific Council of EHT (and was the one who proposed this experiment twenty years ago) – explained in a EHT press release prior to the observation being made:

“It is the challenge of doing something, that has never been attempted before. It is the start of an adventurous journey towards a black hole… However, I think we need more observation campaigns and eventually more telescopes in the network to make a really good image.”

Despite the wait, and the fact that repeated attempts will be needed before we can get our first clear look at a black hole, there is still plenty of reason to celebrate in the meantime. Not only was this a first that was a long time in he making, but it also represents a major leap towards understanding one of the most powerful and mysterious forces of nature.

Given time, the study of black holes may allow for us to finally resolve how gravity and the other fundamental forces of the Universe interact. At long last, we will be able to comprehend all of existence as a single, unified equation!

Further Reading: Event Horizon Telescope, NRAO