The study of Mars’ surface and atmosphere has unlocked some ancient secrets. Thanks to the efforts of the Curiosity rover and other missions, scientists are now aware of the fact that water once flowed on Mars and that the planet had a denser atmosphere. They have also been able to deduce what mechanics led to this atmosphere being depleted, which turned it into the cold, desiccated environment we see there today.

At the same time though, it has led to a rather intriguing paradox. Essentially, Mars is believed to have had warm, flowing water on its surface at a time when the Sun was one-third as warm as it is today. This would require that the Martian atmosphere had ample carbon dioxide in order to keep its surface warm enough. But based on the Curiosity rover’s latest findings, this doesn’t appear to be the case.

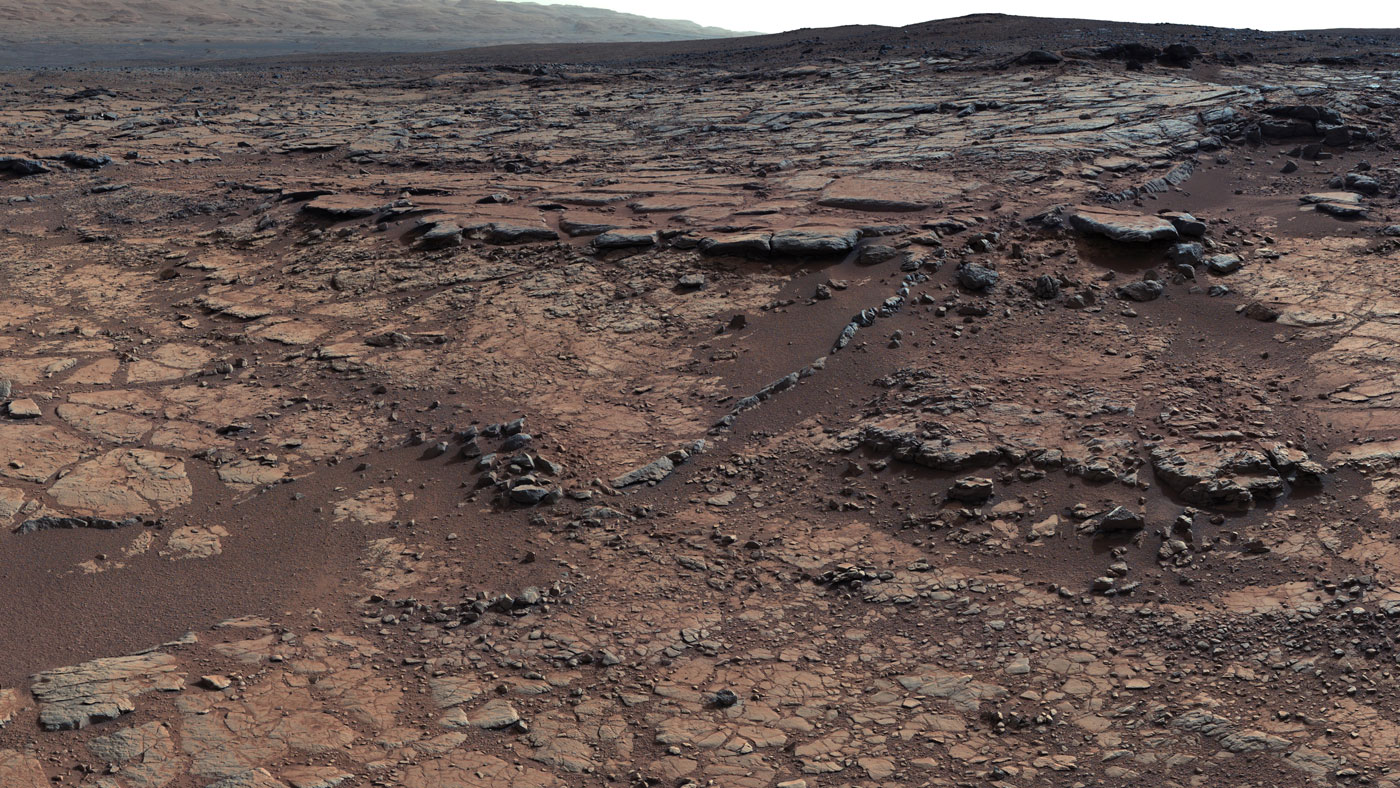

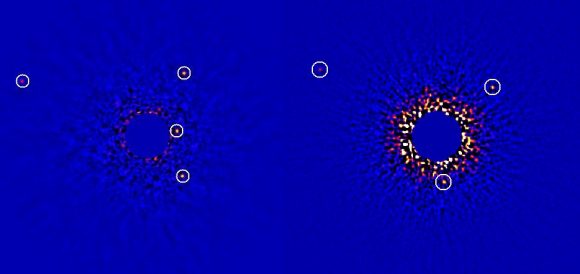

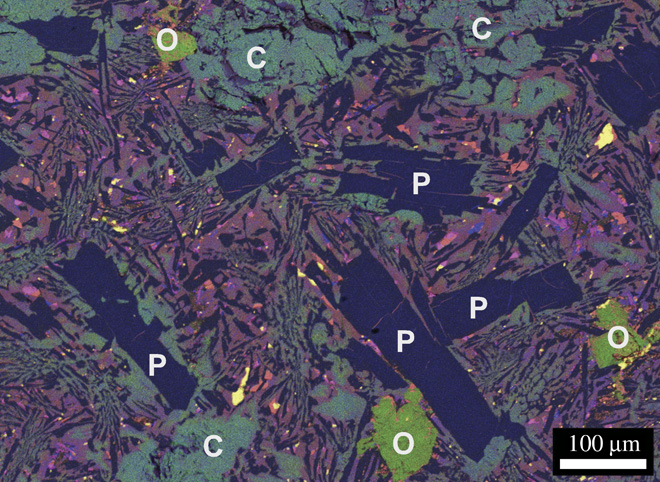

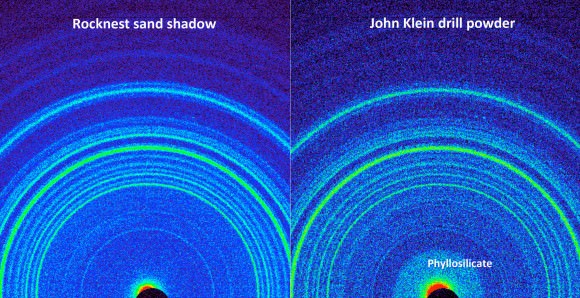

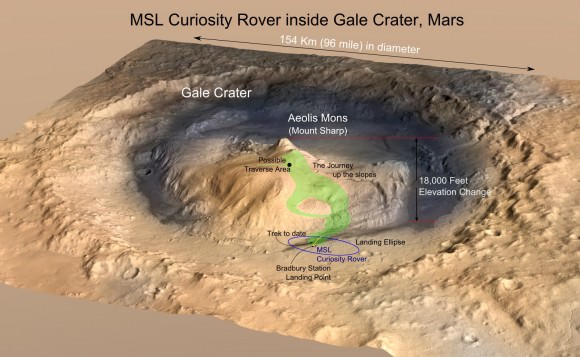

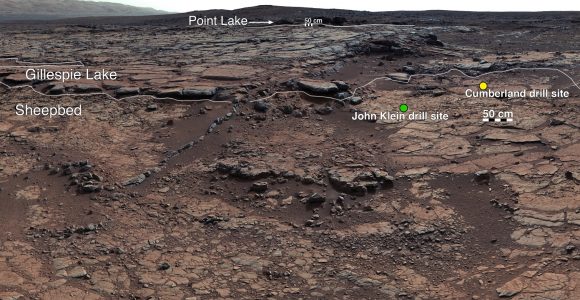

These findings were part of an analysis of data taken by the Curiosity’s Chemistry and Mineralogy X-ray Diffraction (CheMin) instrument, which has been used to study the mineral content of drill samples in the Gale Crater. The results of this analysis were recently published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, where the research team indicated that no traces of carbonates were found in any samples taken from the ancient lake bed.

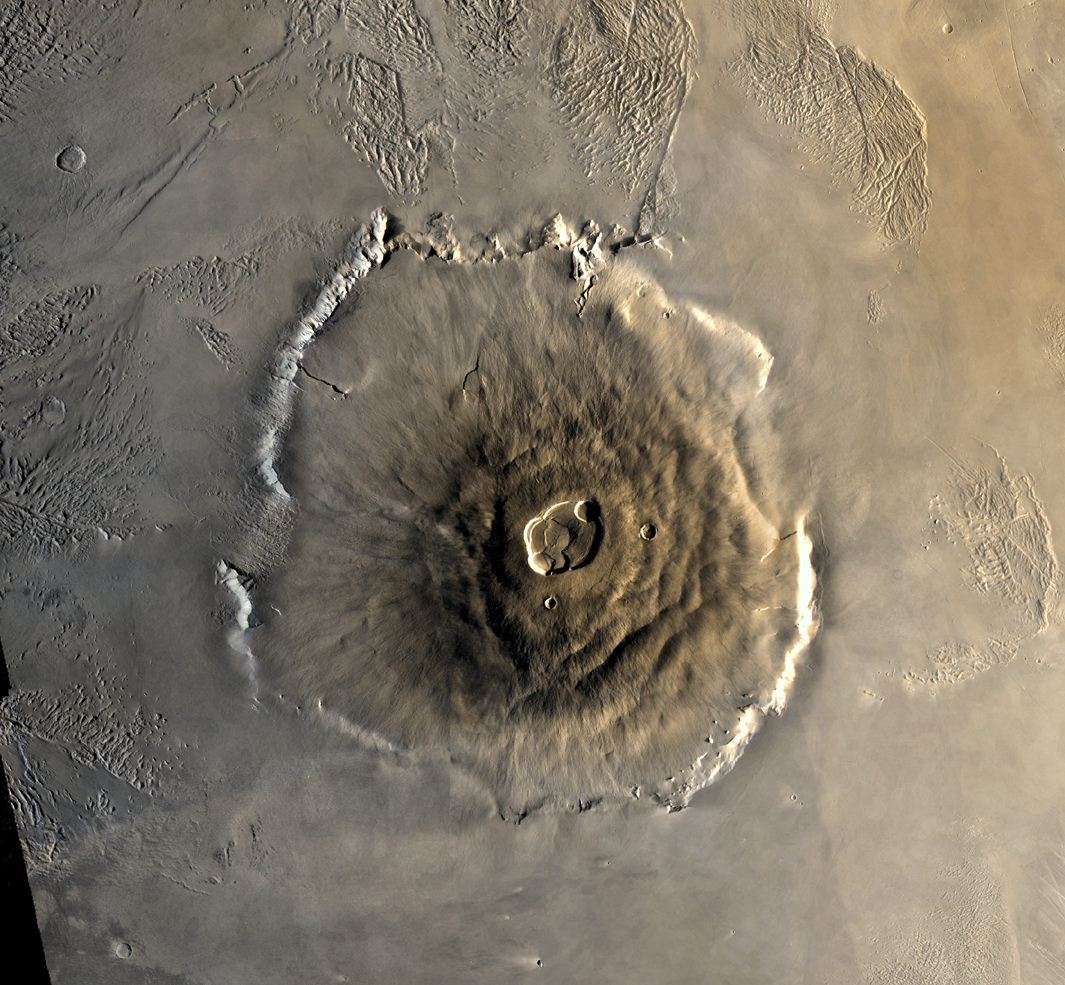

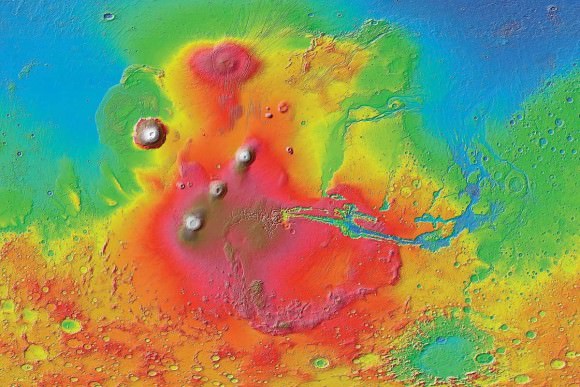

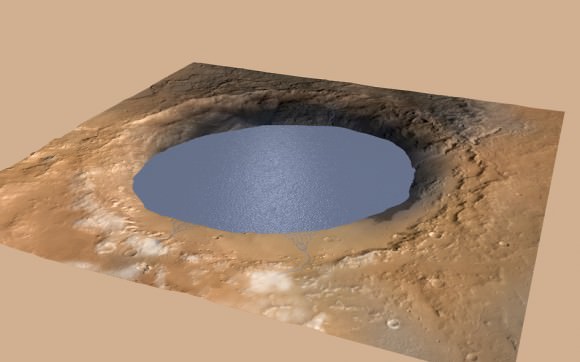

To break it down, evidence collected by Curiosity (and a slew of other rovers, landers and orbiters) has led scientists to conclude that roughly 3.5 billion years ago, Mars surface had lakes and flowing rivers. They have also determined, thanks to the many samples taken by Curiosity since it landed in the Gale Crater in 2011, that this geological feature was once a lake bed that gradually became filled with sedimentary deposits.

However, for Mars to have been warm enough for liquid water to exist, its atmosphere would have had to contain a certain amount of carbon dioxide – providing a sufficient Greenhouse Effect to compensate for the Sun’s diminished warmth. Since rock samples in the Gale Crater act as a geological record for what conditions were like billions of years ago, they would surely contain plenty of carbonate minerals if this were the case.

Carbonates are minerals that result from carbon dioxide combining with positively charged ions (like magnesium and iron) in water. Since these ions have been found to be in good supply in samples of Martian rock, and subsequent analysis has shown that conditions never became acidic to the point that the carbonates would have dissolved, there is no apparent reason why they wouldn’t be showing up.

Along with his team, Thomas Bristow – the principal investigator for the CheMin instrument on Curiosity – calculated what the minimum amount of atmospheric carbon dioxide would need to be, and how this would have been indicated by the levels of carbonate found in Martian rocks today. They then sorted through the years worth of the CheMin instrument’s data to see if there were any indications of these minerals.

But as he explained in a recent NASA press release, the findings simply didn’t measure up:

“We’ve been particularly struck with the absence of carbonate minerals in sedimentary rock the rover has examined. It would be really hard to get liquid water even if there were a hundred times more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere than what the mineral evidence in the rock tells us.”

In the end, Bristow and his team could not find even trace amounts of carbonates in the rock samples they analyzed. Even if just a few tens of millibars of carbon dioxide had been present in the atmosphere when a lake existed in the Gale Crater, it would have produced enough carbonates for Curiosity’s CheMin to detect. This latest find adds to a paradox that has been plaguing Mars researchers for years.

Basically, researchers have noted that there is a serious discrepancy between what surface features indicate about Mars’ past, and what chemical and geological evidence has to say. Not only is there plenty of evidence that the planet had a denser atmosphere in the past, more than four decades of orbital imaging (and years worth of surface data) have yielded ample geomorphological evidence that Mars once had surface water and an active hydrological cycle.

However, scientists are still struggling to produce models that show how the Martian climate could have maintained the types of conditions necessary for this to have been the case. The only successful model so far has been one in which the atmosphere contained a significant amount of CO2 and hydrogen. Unfortunately, an explanation for how this atmosphere could be created and sustained remains elusive.

In addition, the geological and chemical evidence for such a atmosphere existing billions of years ago has also been in short supply. In the past, surveys by orbiters were unable to find evidence of carbonate minerals on the surface of Mars. It was hoped that surface missions, like Curiosity, would be able to resolve this by taking soil and drill samples where water had been known to exist.

But as Bristow explained, his team’s study has effectively closed the door on this:

“It’s been a mystery why there hasn’t been much carbonate seen from orbit. You could get out of the quandary by saying the carbonates may still be there, but we just can’t see them from orbit because they’re covered by dust, or buried, or we’re not looking in the right place. The Curiosity results bring the paradox to a focus. This is the first time we’ve checked for carbonates on the ground in a rock we know formed from sediments deposited under water.”

There are several possible explanations for this paradox. On the one hand, some scientists have argued that the Gale Crater Lake may not have been an open body of water and was perhaps covered in ice, which was just thin enough to still allow for sediments to get in. The problem with this explanation is that if this were true, there would be discernible indications left behind – which would include deep cracks in the soft sedimentary lakebed rock.

But since these indications have not been found, scientists are left with two lines of evidence that do not match up. As Ashwin Vasavada, Curiosity’s Project Scientist, put it:

“Curiosity’s traverse through streambeds, deltas, and hundreds of vertical feet of mud deposited in ancient lakes calls out for a vigorous hydrological system supplying the water and sediment to create the rocks we’re finding. Carbon dioxide, mixed with other gases like hydrogen, has been the leading candidate for the warming influence needed for such a system. This surprising result would seem to take it out of the running.”

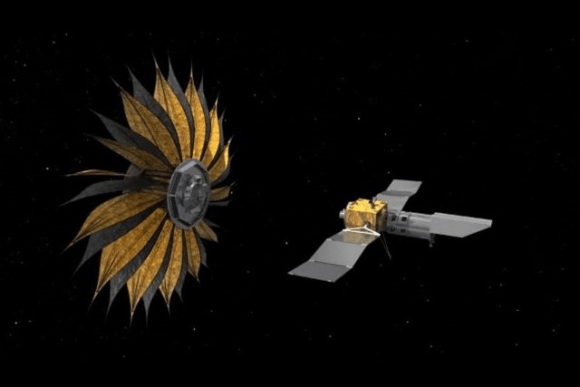

Luckily, incongruities in science are what allow for new and better theories to be developed. And as the exploration of the Martian surface continues – which will benefit from the arrival of the ExoMars and the Mars 2020 missions in the coming years – we can expect additional evidence to emerge. Hopefully, it will help point the way towards a resolution for this paradox, and not complicate our theories even more!

Further Reading: NASA