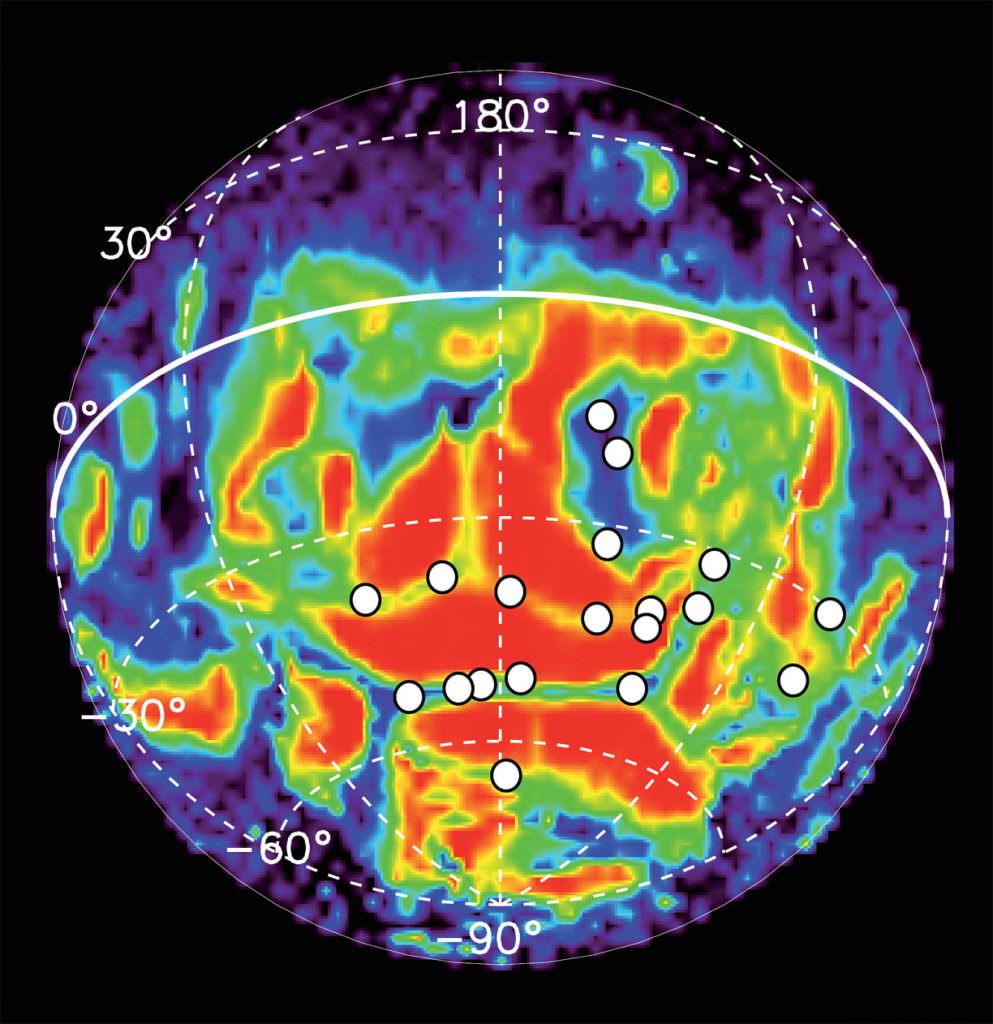

A team of astronomers suggests that an exoplanet named 62f could be habitable. Kepler data suggests that 62f is likely a rocky planet, and could have oceans. The exoplanet is 40% larger than Earth and is 1200 light years away.

62f is part of a planetary system discovered by the Kepler mission in 2013. There are 5 planets in the system, and they orbit a star that is both cooler and smaller than our Sun. The target of this study, 62f, is the outermost of the planets in the system.

Kepler can’t tell us if a planet is habitable or not. It can only tell us something about its potential habitability. The team, led by Aomawa Shields from the UCLA department of physics and astronomy, used different modeling methods to determine if 62f could be habitable, and the answer is, maybe.

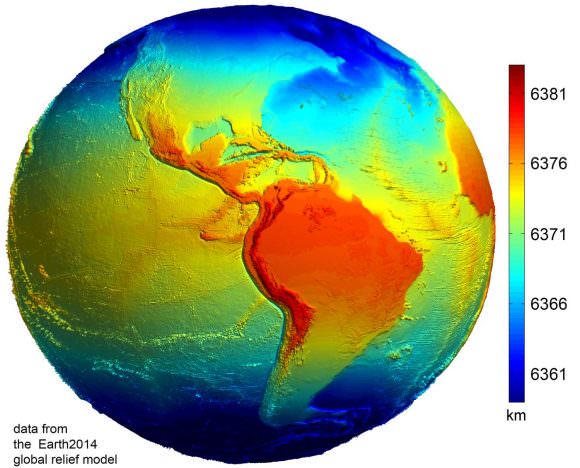

According to the study, much of 62f’s potential habitability revolves around the CO2 component of its atmosphere, if it indeed has an atmosphere. As a greenhouse gas, CO2 can have a significant effect on the temperature of a planet, and hence, a significant effect on its habitability.

Earth’s atmosphere is only 0.04% carbon dioxide (and rising.) 62f would likely need to have much more CO2 than that if it were to support life. It would also require other atmospheric characteristics, .

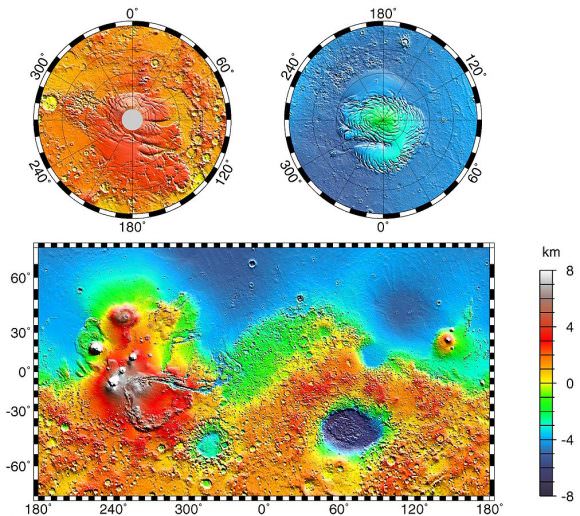

The study modelled parameters for CO2 concentration, atmospheric density, and orbital characteristics. They simulated:

- An atmospheric thickness from the same as Earth’s up to 12 times thicker.

- Carbon dioxide concentrations ranging from the same as Earth’s up to 2500 times Earth’s level.

- Multiple different orbital configurations.

It may look like the study casts its net pretty wide in order to declare a planet potentially habitable. But the simulations were pretty robust, and relied on more than a single, established modelling method to produce these results. With that in mind, the team found that there are multiple scenarios that could make 62f habitable.

“We found there are multiple atmospheric compositions that allow it to be warm enough to have surface liquid water,” said Shields, a University of California President’s Postdoctoral Program Fellow. “This makes it a strong candidate for a habitable planet.”

As mentioned earlier, CO2 concentration is a big part of it. According to Shields, the planet would need an atmospheric entirely composed of CO2, and an atmosphere five times as dense as Earth’s to be habitable through its entire year. That means that there would be 2500 times more carbon dioxide than Earth has. This would work because the planet’s orbit may take it far enough away from the star for water to freeze, but an atmosphere this dense and this high in CO2 would keep the planet warm.

But there are other conditions that would make 62f habitable, and these include the planet’s orbital characteristics.

“But if it doesn’t have a mechanism to generate lots of carbon dioxide in its atmosphere to keep temperatures warm, and all it had was an Earth-like amount of carbon dioxide, certain orbital configurations could allow Kepler-62f’s surface temperatures to temporarily get above freezing during a portion of its year,” said Shields. “And this might help melt ice sheets formed at other times in the planet’s orbit.”

Shields and her team used multiple modelling methods to produce these results. The climate was modelled using the Community Climate System Model and the Laboratoire de Me´te´orologie Dynamique Generic model. The planet’s orbital characteristics were modelled using HNBody. This study represents the first time that these modelling methods were combined, and this combined method can be used on other planets.

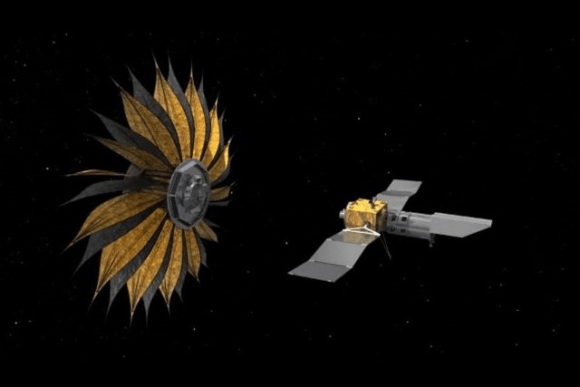

Shields said, “This will help us understand how likely certain planets are to be habitable over a wide range of factors, for which we don’t yet have data from telescopes. And it will allow us to generate a prioritized list of targets to follow up on more closely with the next generation of telescopes that can look for the atmospheric fingerprints of life on another world.”

There are over 2300 confirmed exoplanets, and many more candidates yet to be confirmed. Only a handful of them have been confirmed as being in the habitable zone around their host star. Of course, we don’t know if life can exist on other planets, even if they do reproduce the same kind of habitability that Earth has. We just have no way of knowing, yet.

That will change when instruments like the James Webb Space Telescope are able to peer into the atmospheres of exoplanets and tell us something about any bio-markers that might be present.

But until then, and until we actually visit another world with a probe of some design, we need to use modelling like the type employed in this study, to get us closer to answering the question of life on other worlds.