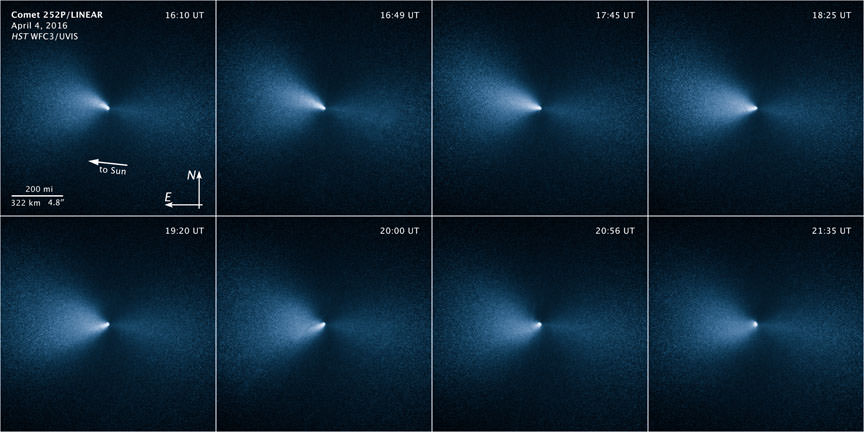

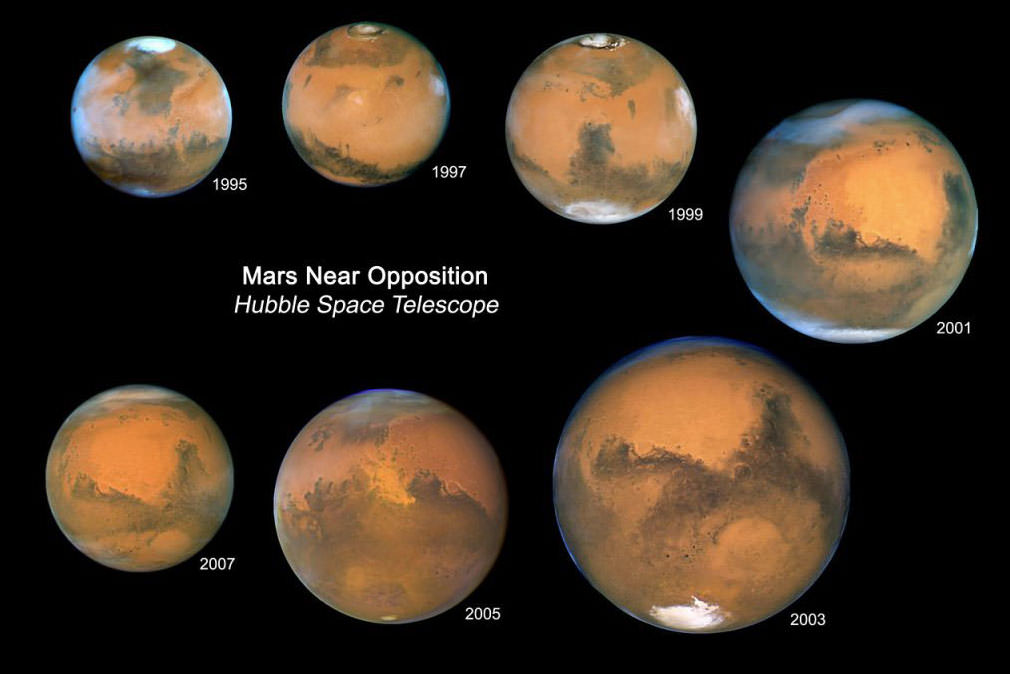

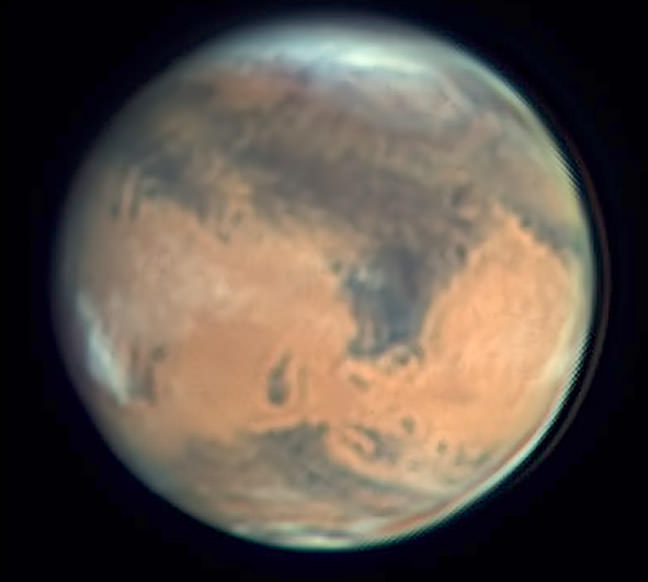

We’re in store for an exciting weekend as the Earth and Mars get closer to each other than at any time in the last ten years. To take advantage of this special opportunity, the Hubble Space Telescope, normally busy eyeing remote galaxies, was pointed at our next door neighbor to capture this lovely close-up image.

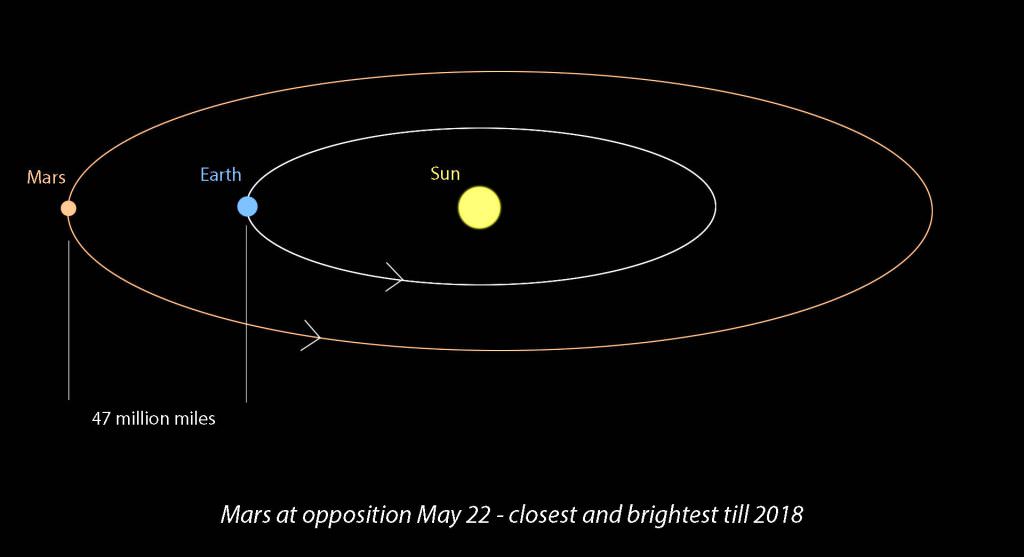

As Universe Today writer David Dickinson described in his excellent Mars guide, the planet reaches opposition on Sunday morning May 22. That’s when the planet will be directly opposite the Sun in the sky and rise in the east around the same time the Sun sets in the west. Earth sits squarely in between. Opposition also marks the planet’s close approach to Earth, so that Mars appears bigger and brighter in the sky than usual. A perfect time for detailed studies whether through both amateur and professional telescopes.

Although opposition for most outer planets coincides with the date of closest approach, that’s not true in the case of Mars. If Mars is moving away from the Sun in its orbit when Earth laps it, closest approach occurs a few days before opposition. But if the planet is moving toward the Sun when our planet passes by, closest approach occurs a few days after opposition. This time around, Mars is headed sunward, so the date of closest approach of the two planets occurs on May 30.

It’s all goes back to Mars’ more eccentric orbit, which causes even a few days worth of its orbital travels to make a difference in the distance between the two planets when Earth is nearby. On May 22, Mars will be 47.4 million miles away vs. 46.77 million on the 30th, a difference of about 700,000 miles.

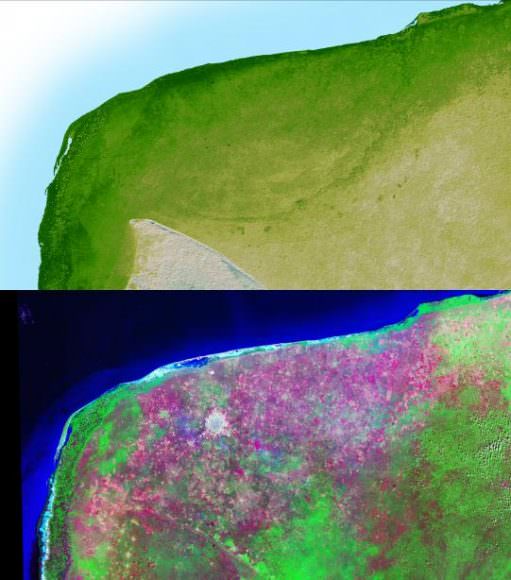

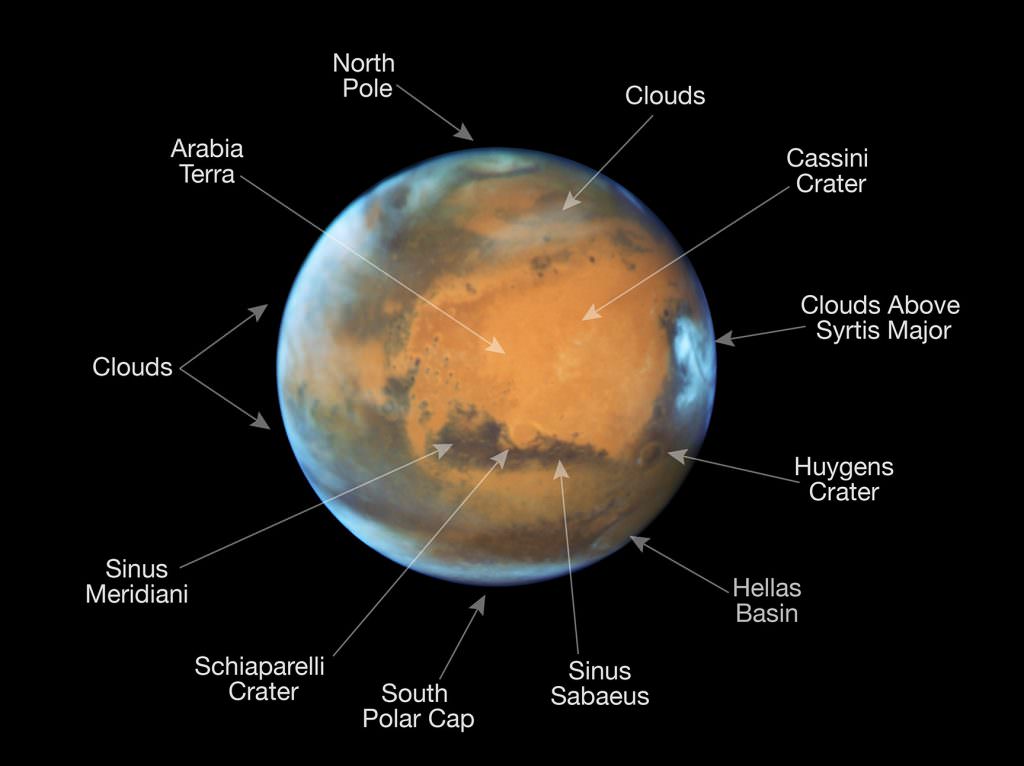

On May 12, Hubble took advantage of this favorable alignment and turned its gaze towards Mars to take an image of our rusty-hued neighbor, From this distance the telescope could see Martian features as small as 18.6 miles (30 kilometers) across. The image shows a sharp, natural-color view of Mars and reveals several prominent geological features, from smaller mountains and erosion channels to immense canyons and volcanoes.

The orange area in the center of the image is Arabia Terra, a vast upland region. The landscape is densely cratered and heavily eroded, indicating that it could be among the oldest features on the planet.

South of Arabia Terra, running east to west along the equator, is the long dark feature named Sinus Sabaeus that terminates in a larger, dark blob called and Sinus Meridiani. These darker regions are covered by bedrock from ancient lava flows and other volcanic features. An extended blanket of clouds can be seen over the southern polar cap where it’s late winter. The icy northern polar cap has receded to a comparatively small size because it’s now late summer in the northern hemisphere.

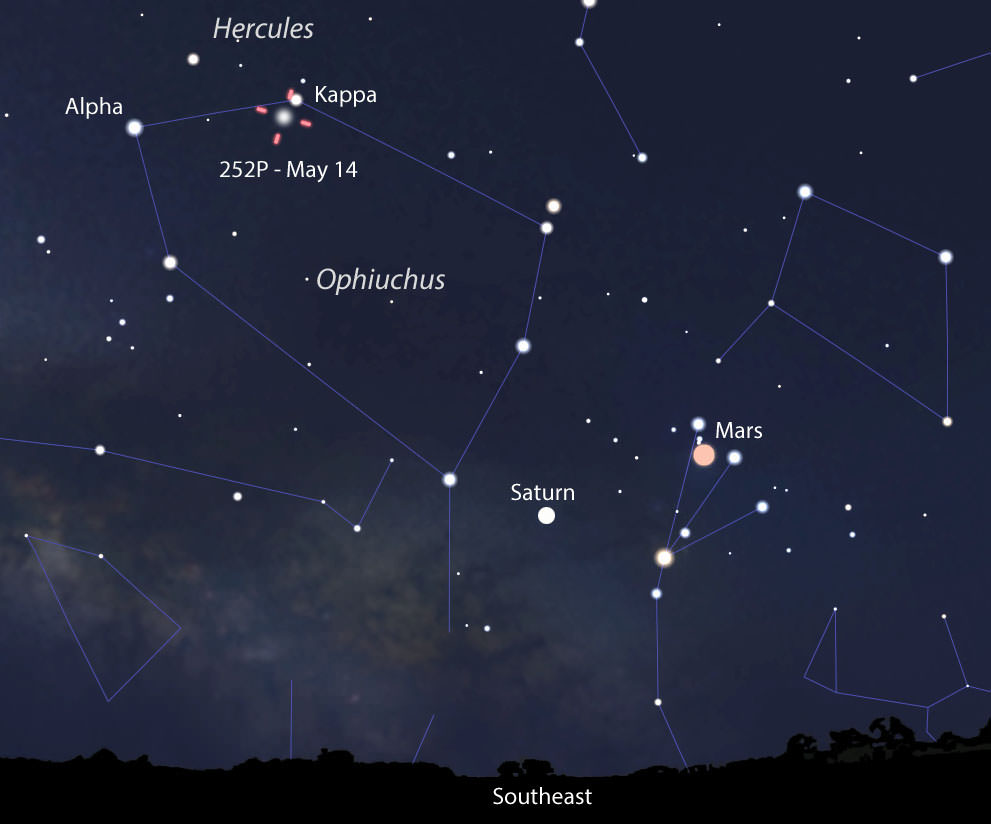

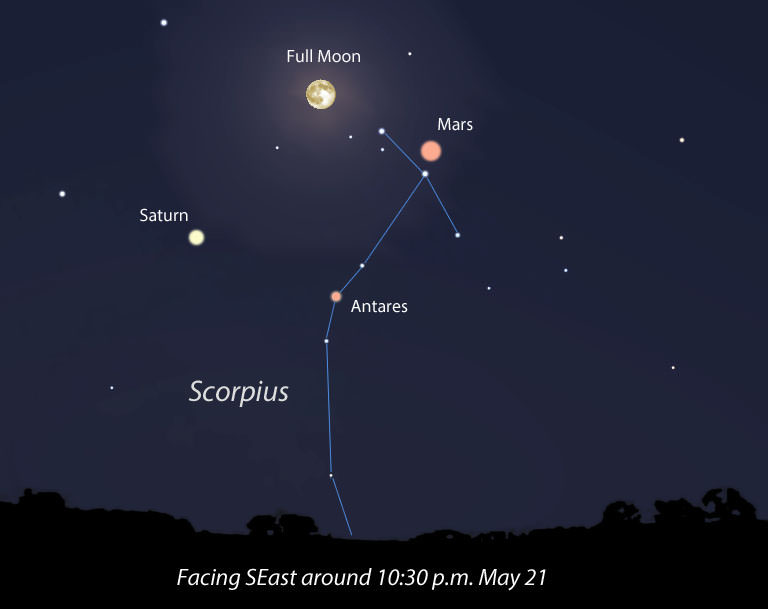

So the question now is how much will you see as we pull up alongside the Red Planet this weekend? With the naked eye, Mars looks like a fiery “star” in the head of Scorpius the scorpion not far from the similarly-colored Antares, the brightest star in the constellation. It’s unmistakable. Even through the haze it caught my eye last night, rising in the southeast around 10 o’clock with its signature hue.

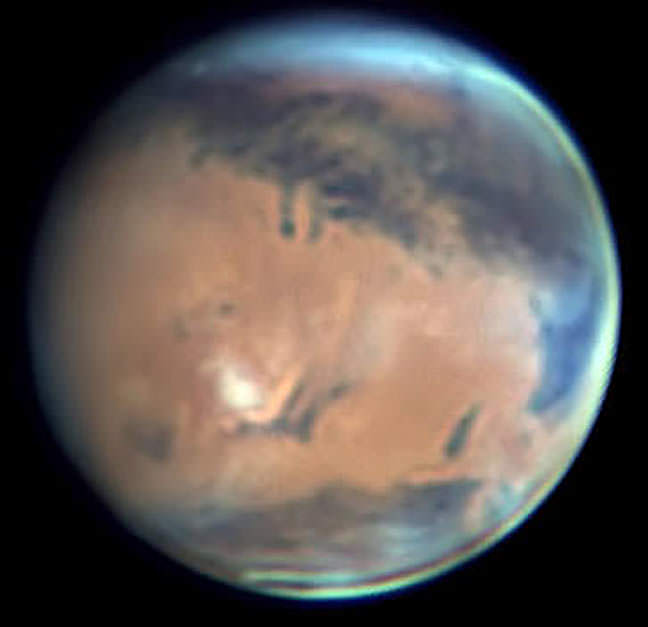

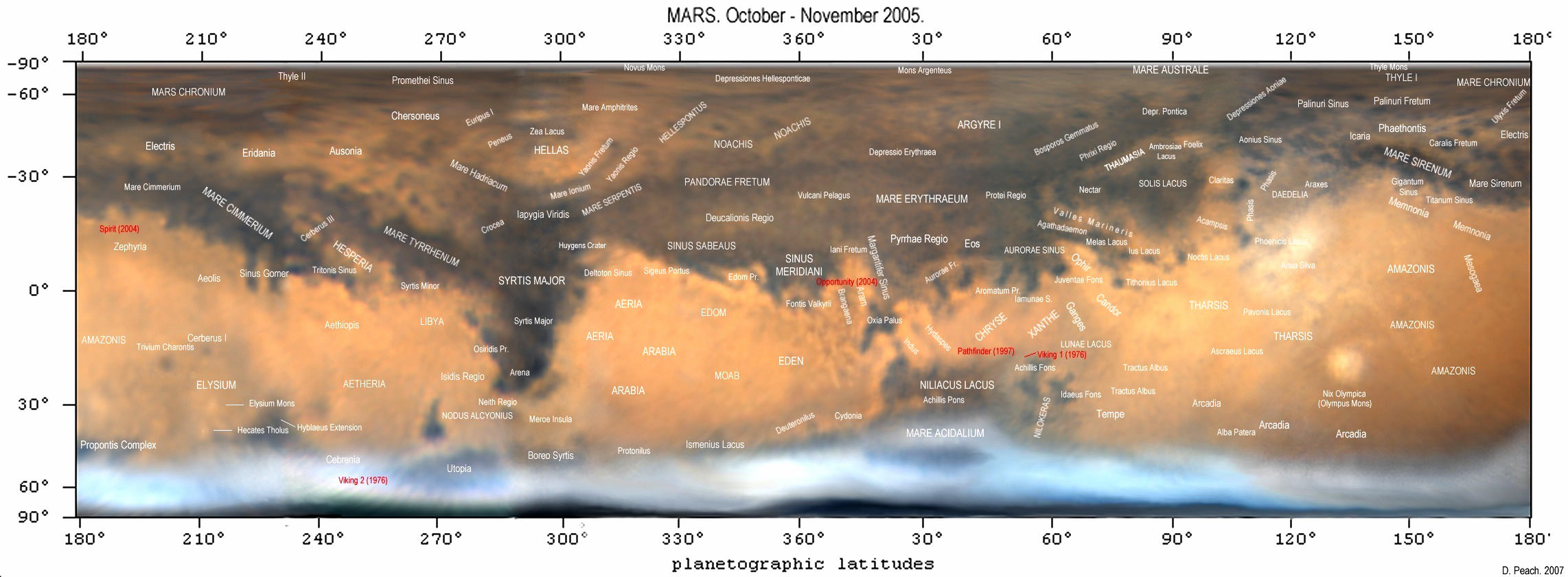

Through a 4-inch or larger telescope, you can see limb hazes/clouds and prominent dark features such as Syrtis Major, Utopia, clouds over Hellas, Mare Tyrrhenum (to the west of Syrtis Major) and Mare Cimmerium (west of M. Tyrrhenum).

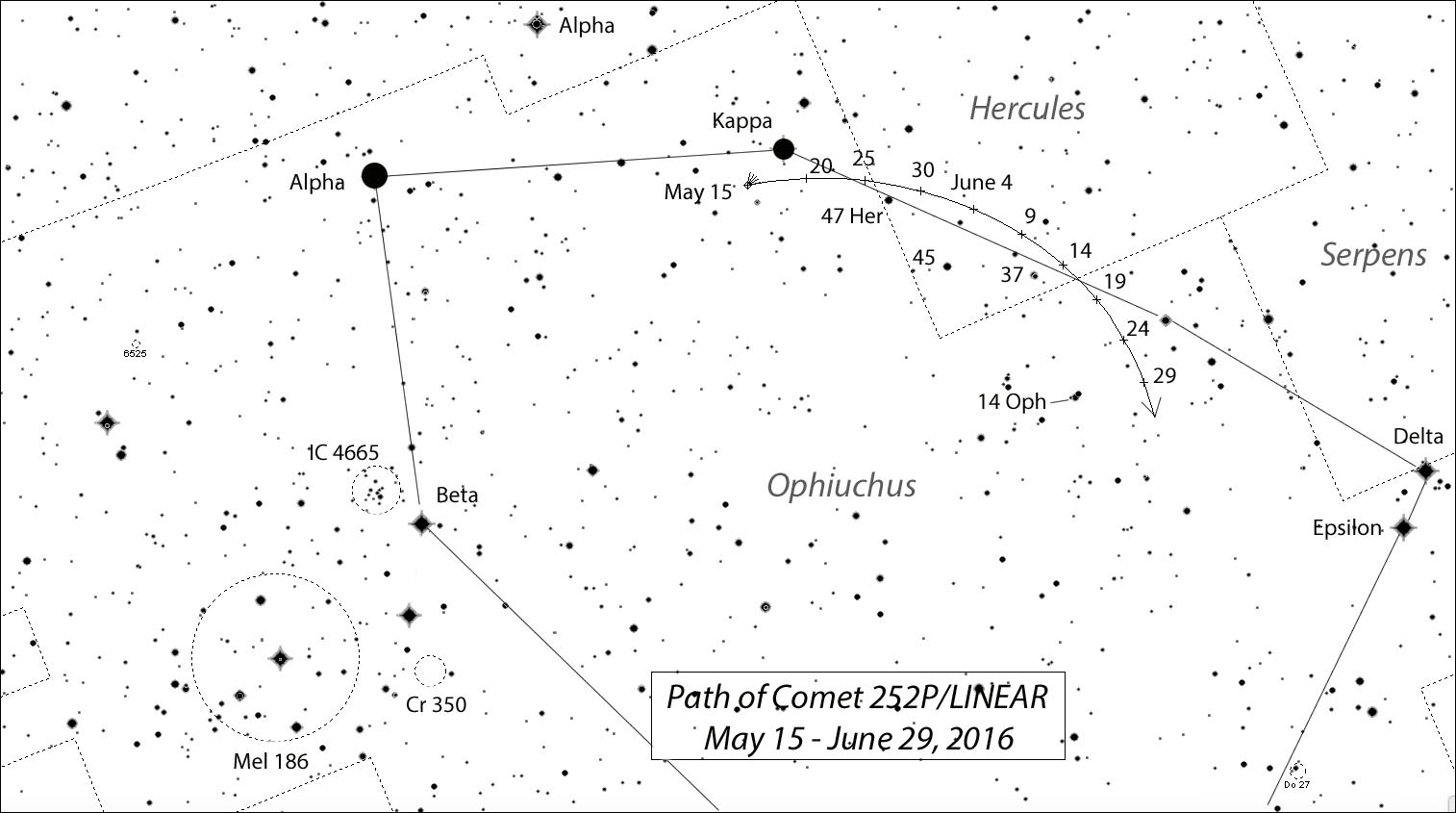

These features observers across the America will see this week and early next between about 11 p.m. and 2 a.m. local time. As Mars rotation period is 37 minutes longer than Earth’s, these markings will gradually rotate out of view, and we’ll see the opposite hemisphere in the coming weeks. You can use the map to help you identify particular features or Sky & Telescope’s handy Mars Profiler to know which side of the planet’s visible when.

To top off all the good stuff happening with Mars, the Full Flower Moon will join up with that planet, Saturn and Antares Saturday night May 21 to create what I like to call a “diamond of celestial lights” visible all night. Don’t miss it!

Italian astronomer Gianluca Masi will offer up two online Mars observing sessions in the coming week, on May 22 and 30, starting at 5 p.m. CDT (22:00 UT). Yet another opportunity to get acquainted with your inner Mars.