On March 22, Comet P/2016 BA14 (Pan-STARRS) flew just 2.2 million miles (3.5 million kilometers) from Earth, making it the third closest comet ever recorded. The last time a comet appeared on our doorstep was in 1770, when Lexell’s Comet breezed by at about half that distance. Through a telescope, comet BA14 looked (and still looks) like a faint star, though time exposures reveal a short, weak tail. With an excellent map and large amateur telescope you might still find it making a bead across the Big Dipper and constellation Bootes tonight through the weekend.

Flyby Comet Imaged by Radar

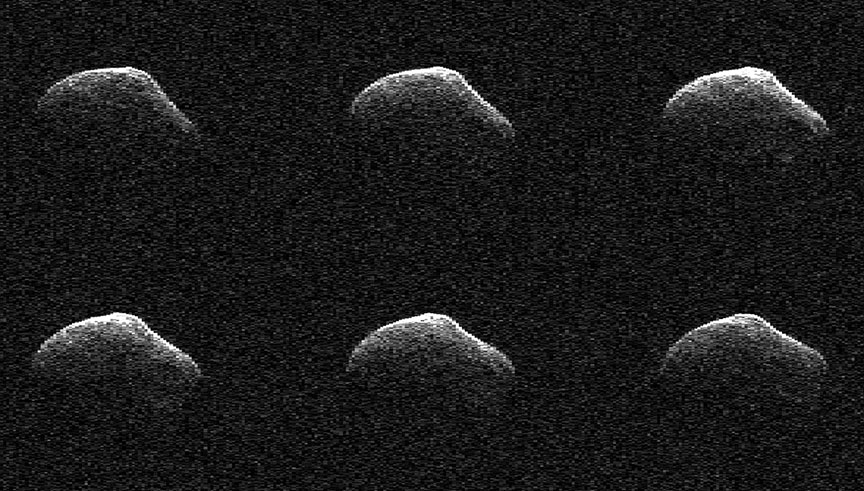

While normal telescopes show few details, NASA’s Goldstone Solar System Radar in California’s Mojave Desert pinged P/2016 BA14 with radar over three nights during closest approach and created a series of crisp, detailed images from the returning echoes. They show a bigger comet than expected — about 3,000 feet (one kilometer) across — and resolve features as small as 26 feet (8 meters) across.

“The radar images show that the comet has an irregular shape: looks like a brick on one side and a pear on the other,” said Shantanu Naidu, a researcher at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “We can see quite a few signatures related to topographic features such as large flat regions, small concavities and ridges on the surface of the nucleus.”

I honestly thought we’d see a more irregular shape assuming that astronomers were correct in thinking that BA14 broke off from its parent 252P/LINEAR though it’s possible it happened so long ago that the “damage” has been repaired by vaporizing ice softening its contours.

Radar also shows that the comet is rotating on its axis once every 35 to 40 hours. While radar eyes focused on BA14, Vishnu Reddy, of the Planetary Science Institute, Tucson, Arizona, used the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility (IRTF) on Mauna Kea, Hawaii to examine the comet in infrared light. He discovered its dark surface reflects less than 3% of the sunlight that falls on it. The infrared data is expected to yield clues of the comet’s composition as well.

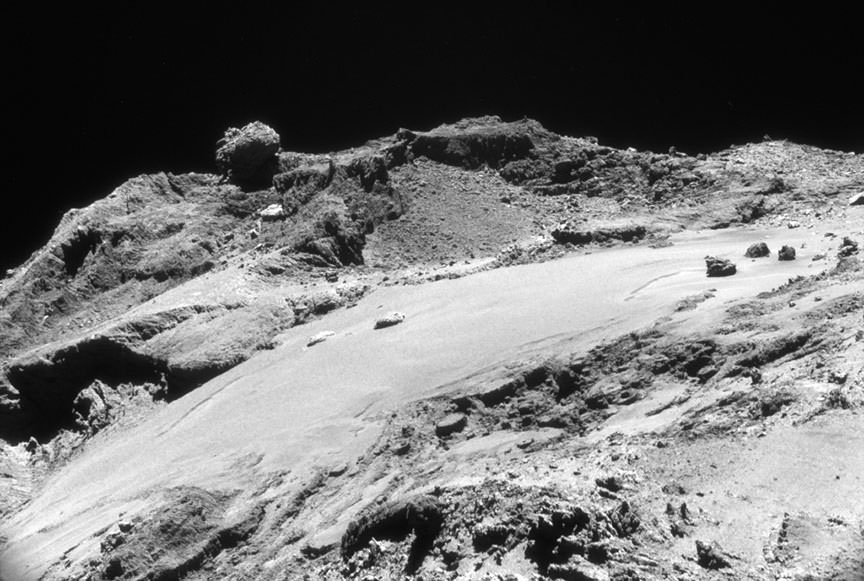

Comets are exceptionally dark objects often compared to the appearance of a fresh asphalt road or parking lot. They appear bright in photos because seen against the blackness of space, they’re still reflective enough to stand out. Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, still the apple of the orbiter Rosetta’s eye, is similarly dark, reflecting about 4% of sunlight.

What makes comets so dark even though they composed primarily of ice? Astronomers believe a comet grows a dark ‘skin’ both from accumulated dust and irradiation of its pristine ices by cosmic rays. Cosmic rays loosen oxygen atoms from water ice, freeing them to combine with simple carbon molecules present on comets to form larger, more complex and darker compounds resembling tars and crude oil. Dust settles on a comet’s surface after it’s set free from ice that vaporizes in sunlight.

I live in Minnesota, where our annual State Fair features every kind of deep-fried food you can imagine: deep-fried Twinkies, deep-fried fruit, deep-fried bacon and even deep-fried Smores. Just now, I can’t shake the thought that comets are just another deep-fried confection made of pristine, 4.5-billion-year-old ice toasted by eons of sunlight and cosmic bombardment.