A spectacular annular eclipse of the Sun was witnessed across Australia and the southern Pacific region early today. Morning dawned mostly clear across the Australian continent, and those who journeyed out to meet the antumbra of the Moon as the Sun rose across the Great Sandy Desert and the Cape York Peninsula were not disappointed. The rest of us watched worldwide on as Slooh and a scattering of other ad-hoc broadcasts delivered the celestial event to us via the web.

This was a challenging one. Although partial phases of the eclipse was visible across the entirety of Australia, Hawaii, and as far north as the Philippines and as far south as New Zealand, the track of annularity passed over some very remote locales. Stable Internet connections were scarce, and many photos and videos are still trickling in as die-hard eclipse chasers return “from the Bush.”

One lucky witness to the eclipse was Druce Horton (Xylopia on flickr) who caught the eclipse from Kuranda, Australia just north of Cairns. “It was completely clouded over here in Kuranda and I didn’t even bother going to a place where I could get a clear view.” Druce told Universe Today. “I then noticed the sky lightening a little and I rushed out with the camera and desperately tried to set an appropriate exposure and frame it while avoiding getting an eyeful of sunlight and/or a tree branch in the way.”

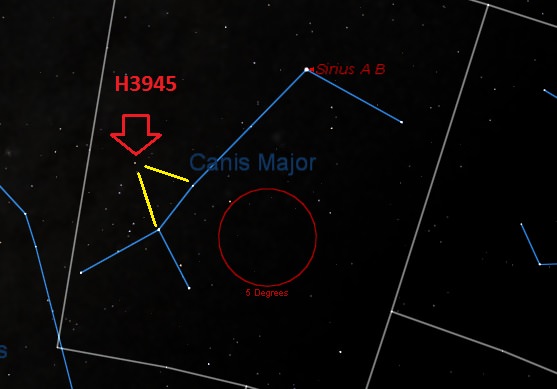

As pointed out the us by Michael Zeiler (@EclipseMaps) earlier this week, the town of Newman and surrounding regions in Western Australia were a great place to witness the rising annular eclipse. Geoffrey Sims ventured out and did just that:

Note how the atmospheric haze is distorting the solar annulus into a flattened ring… pure magic! Mr. Sims got some truly stunning pictures of the eclipse, and was one of the first to manage to get them out onto the Internet, though he stated on Twitter that it “will likely take weeks to sort through the images!”

All get reasons to keep a close eye on Mr. Sims’ Facebook page…

Mr. Joerg Schoppmeyer also ventured about 70 kilometres south of Newman to catch the rising “Ring of Fire”:

We also mentioned earlier this week how you can use the “strainer effect” to create a flock of crescent Suns during a partial solar eclipse.

Amanda Bauer (@astropixie) of Sydney, Australia did just this to create her name in “eclipse pacmans”:

And speaking of which, eclipse crescents can turn up in the most bizarre of places, such as a lens flare caught by a webcam based at the Canberra Deep Space Network:

Trevor Sellman (@tsellman) based in northern Melbourne preferred to catch sight of the partial phase of the eclipse “the old fashioned way,” via a simple pinhole projection onto a white sheet of paper:

In addition to Slooh, the Mead West Vaco Observatory in conjunction with the Columbus State University’s Coca-Cola Space Science Center provided an excellent webcast of the full phases of the eclipse, and in multiple wavelengths to boot:

And they also provided a view in Calcium-K:

But Earth bound-observers weren’t the only ones on hand to witness this eclipse. Roskosmos also released a video animation of the antumba of the Moon crossing the Earth as seen from the Elektro-L satellite:

“These images interest Russian space enthusiasts because we asked Roskosmos to optimize (the) work of satellite for best pictures of eclipse,” Vitaliy Egorov told Universe Today.

There’s no word as of yet if the NASA/JAXA spacecraft Hinode or if ESA’s Proba-2 caught the eclipse, although they were positioned to take advantage of the opportunity.

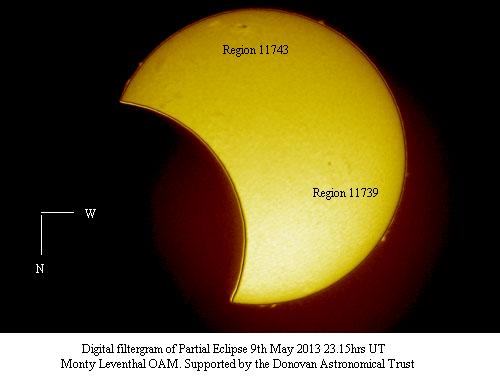

There were also some active sunspot regions on the Earthward face of the Sun, as captured by Monty Leventhal in this outstanding white-light filtered image:

Another fine video animation of the eclipse turned up courtesy of Steve Swayne of Maleny in Queensland, Australia;

And finally, Vanessa Hill caught the partial stage of the eclipse while observing from the CSIRO Astrophysics & Space Sciences viewing event:

Partial stages of the eclipse were also captured by Carey Johnson (@TheTelescopeGuy) from Hawaii and can be viewed on his flickr page.

If this eclipse left you jonesin’ for more, there’s a hybrid solar eclipse across the Atlantic and central Africa on November 3rd 2013. Maximum totality for this eclipse is 1 minute and 40 seconds. Unfortunately, after two solar eclipses in 6 months, another total solar eclipse doesn’t grace the Australian continent until July 22nd, 2028!

But such are the ways of the cosmos and celestial mechanics… hey, be glad we occupy a position in space and time where solar eclipses can occur.

Thanks to all who sent in photos… if you’ve got a picture of today’s eclipse, an anecdote, or just a tale of triumph and/or eclipse chasing tribulations drop us a line & share those pics up to the Universe Today flickr group. See you next syzygy, and may all your eclipse paths be clear!