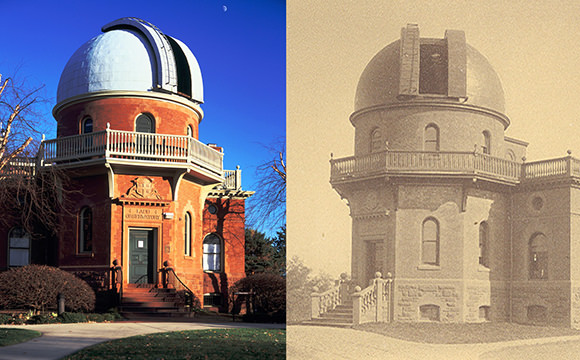

Today, in a remote part of the Chilean Andes, the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), was inaugurated at an official ceremony. This event marks the completion of all the major systems of the giant telescope and the formal transition from a construction project to a fully fledged observatory. ALMA is a partnership between Europe, North America and East Asia in cooperation with the Republic of Chile.

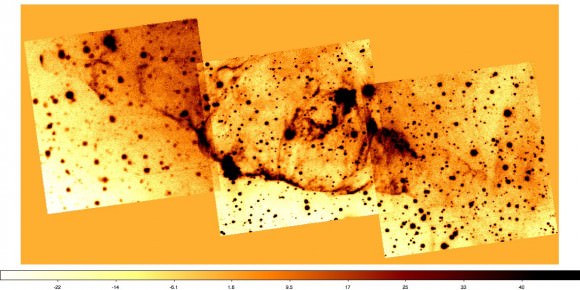

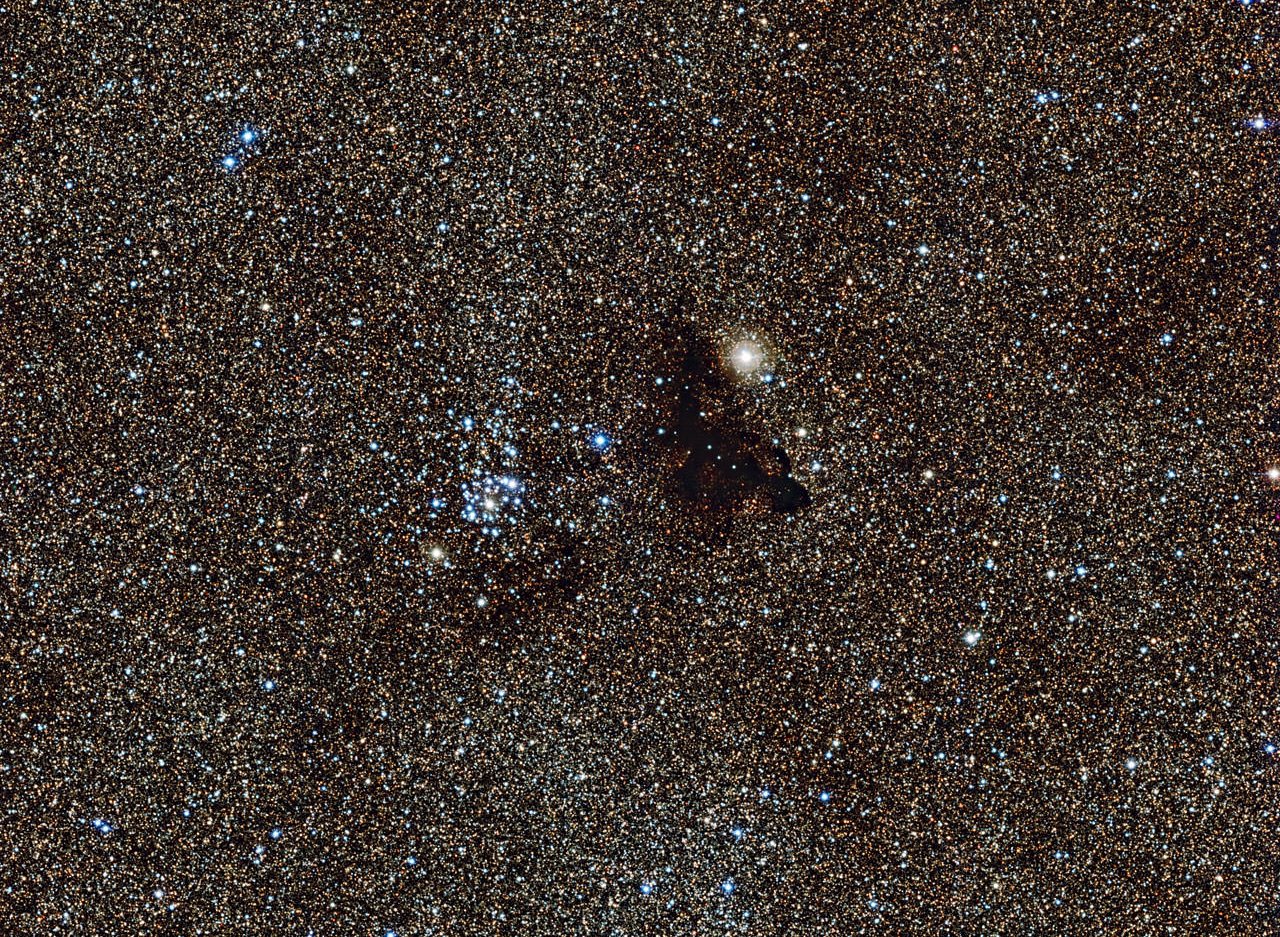

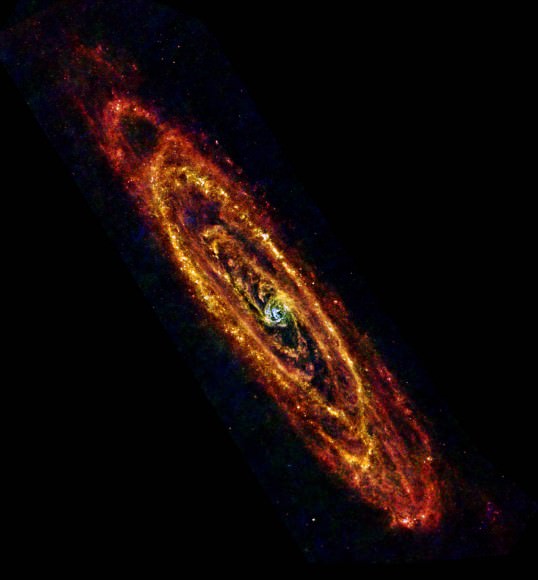

ALMA is able to observe the Universe by detecting light that is invisible to the human eye, and will show us never-before-seen details about the birth of stars, infant galaxies in the early Universe, and planets coalescing around distant suns. It also will discover and measure the distribution of molecules — many essential for life — that form in the space between the stars.

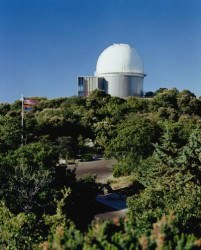

ALMA’s three international partners today welcomed more than 500 people to the ALMA Observatory in the Chilean Atacama Desert to celebrate the success of the project. The guest of honour was the President of Chile, Sebastián Piñera.

In honor of the official inauguration of ALMA, this movie, called ALMA — In Search of Our Cosmic Origins, has been released:

The President of Chile, Sebastián Piñera, said: “One of our many natural resources is Chile’s spectacular night sky. I believe that science has been a vital contributor to the development of Chile in recent years. I am very proud of our international collaborations in astronomy, of which ALMA is the latest, and biggest outcome.”

The Director of ALMA, Thijs de Graauw, expressed his expectations for ALMA. “Thanks to the efforts and countless hours of work by scientists and technicians in the ALMA community around the world, ALMA has already shown that it’s the most advanced millimetre/submillimetre telescope in existence, dwarfing anything else we had before. We are eager for astronomers to exploit the full power of this amazing tool.”

The observatory was conceived as three separate projects in Europe, USA and Japan in the 1980s, and merged to one in the 1990s. Construction started in 2003. The total construction cost of ALMA is approximately US$ 1.4 billion.

The antennas of the ALMA array, fifty-four 12-metre and twelve smaller 7-meter dish antennas, work together as a single telescope. Each antenna collects radiation coming from space and focuses it onto a receiver. The signals from the antennas are then brought together and processed by a specialized supercomputer: the ALMA correlator. The 66 ALMA antennas can be arranged in different configurations, where the maximum distance between antennas can vary from 150 meters to 16 kilometers.

Source: ESO