[/caption]

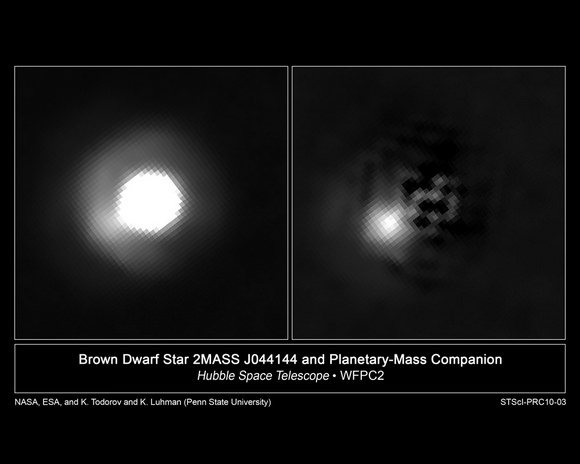

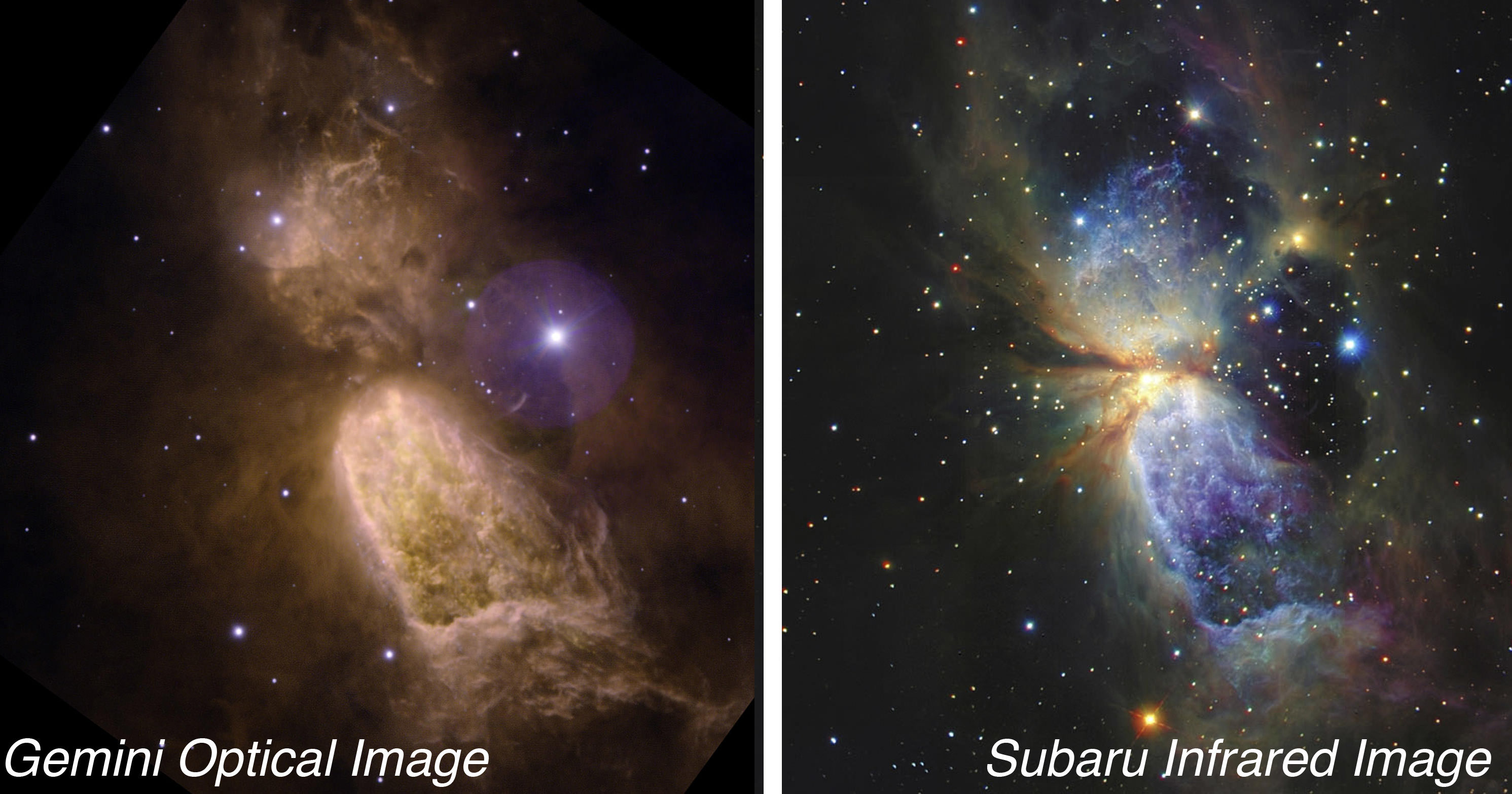

Big planet or companion brown dwarf? Using the Hubble Space Telescope and the Gemini Observatory, astronomers have discovered an unusual object orbiting a brown dwarf, and its discovery could fuel additional debate about what exactly constitutes a planet. The object circles a nearby brown dwarf in the Taurus star-forming region with an orbit approximately 3.6 billion kilometers (2.25 billion miles) out, about the same as Saturn from our sun. The astronomers say it is the right size for a planet, but they believe the object formed in less than 1 million years — the approximate age of the brown dwarf — and much faster than the predicted time it takes to build planets according to conventional theories.

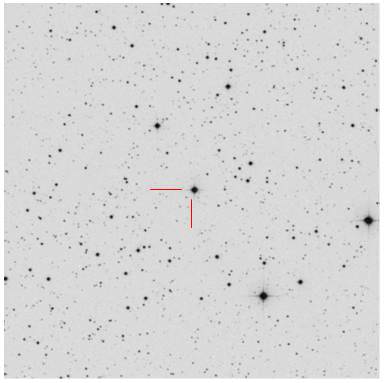

Kamen Todorov of Penn State University and his team conducted a survey of 32 young brown dwarfs in the Taurus region.

The object orbits the brown dwarf 2M J044144 and is about 5-10 times the mass of Jupiter. Brown dwarfs are objects that typically are tens of times the mass of Jupiter and are too small to sustain nuclear fusion to shine as stars do.

While there has been a lot of discussion in the context of the Pluto debate over how small an object can be and still be called a planet, this new observation addresses the question at the other end of the size spectrum: How small can an object be and still be a brown dwarf rather than a planet? This new companion is within the range of masses observed for planets around stars, but again, the astronomers aren’t sure if it is a planet or a companion brown dwarf star.

The answer is strongly connected to the mechanism by which the companion most likely formed.

The Hubble new release offers these three possible scenarios for how the object may have formed:

Dust in a circumstellar disk slowly agglomerates to form a rocky planet 10 times larger than Earth, which then accumulates a large gaseous envelope; a lump of gas in the disk quickly collapses to form an object the size of a gas giant planet; or, rather than forming in a disk, a companion forms directly from the collapse of the vast cloud of gas and dust in the same manner as a star (or brown dwarf).

If the last scenario is correct, then this discovery demonstrates that planetary-mass bodies can be made through the same mechanism that builds stars. This is the likely solution because the companion is too young to have formed by the first scenario, which is very slow. The second mechanism occurs rapidly, but the disk around the central brown dwarf probably did not contain enough material to make an object with a mass of 5-10 Jupiter masses.

“The most interesting implication of this result is that it shows that the process that makes binary stars extends all the way down to planetary masses. So it appears that nature is able to make planetary-mass companions through two very different mechanisms,” said team member Kevin Luhman of the Center for Exoplanets and Habitable Worlds at Penn State University.

If the mystery companion formed through cloud collapse and fragmentation, as stellar binary systems do, then it is not a planet by definition because planets build up inside disks.

The mass of the companion is estimated by comparing its brightness to the luminosities predicted by theoretical evolutionary models for objects at various masses for an age of 1 million years.

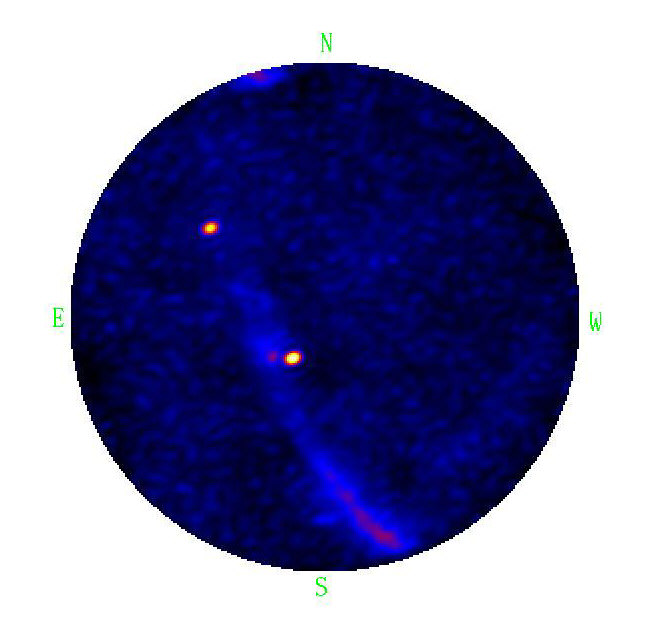

Further supporting evidence comes from the presence of a very nearby binary system that contains a small red star and a brown dwarf. Luhman thinks that all four objects may have formed in the same cloud collapse, making this in actuality a quadruple system.

“The configuration closely resembles quadruple star systems, suggesting that all of its components formed like stars,” he said.

The team’s research is being published in an upcoming issue of The Astrophysical Journal.

The team’s paper: Discovery of a Planetary-Mass Companion to a Brown Dwarf in Taurus

Source: HubbleSite