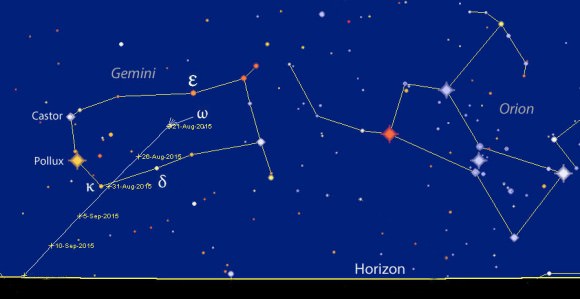

How about that perigee Full Moon this past weekend? Thus begins ‘Supermoon season’ for 2015, as this month’s Full Moon occurs even closer to perigee — less than an hour apart, in fact — on September 28th, with the final total lunar eclipse of the ongoing tetrad to boot. Keep an eye on Luna this week, as it crosses into the early AM sky for several key dates with destiny just prior to the start of the second and final eclipse season for 2015.

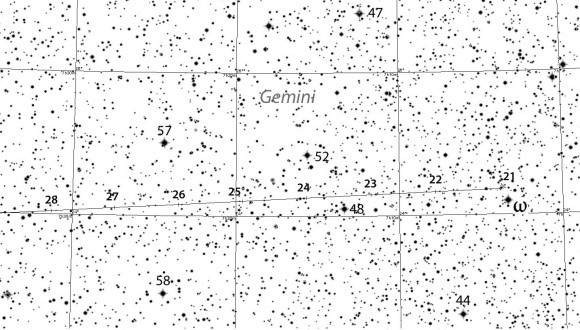

The big event later this week is a passage of the waning gibbous Moon through the Hyades open cluster on the morning of Saturday, September 5th, climaxing with a dramatic occultation of the bright star Aldebaran on the same morning. This is part of a series of 49 ongoing occultations of Aldebaran by the Moon, one for each lunation extending out to September 2018.

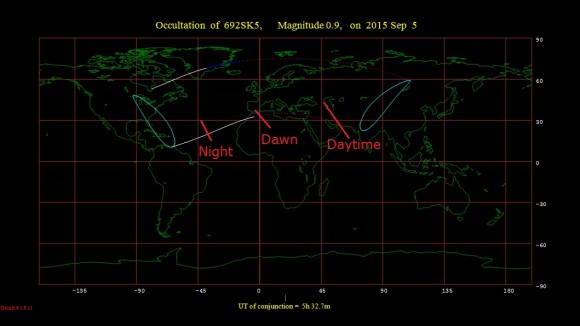

This weekend’s event will occur at moonrise under nighttime skies for the northeastern United States and the Canadian Maritimes, and near dawn and under daytime skies for observers in Western Europe and Northern Africa eastward. We observed an occultation of Aldebaran by the Moon under daytime skies from Alaska back in the late 1990s, and can attest that the star is indeed visible near the limb of the Moon in binoculars. A good deep blue sky is key to spotting +1 magnitude Aldebaran in the daytime.

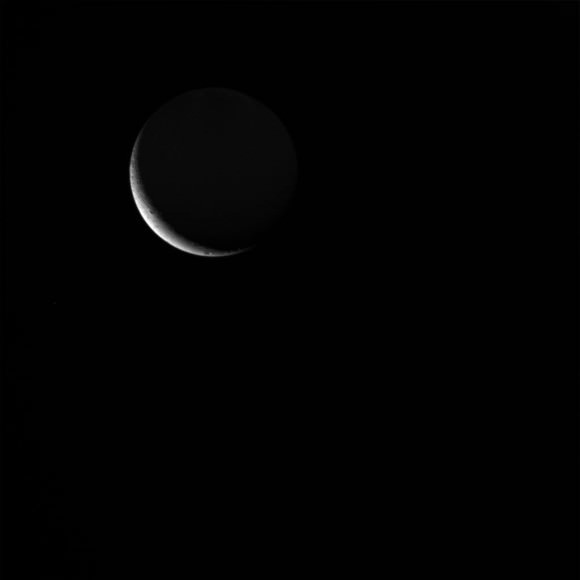

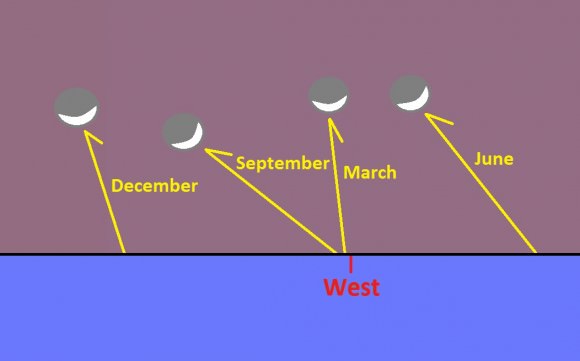

During waning phase, the bright edge of the Moon is always leading, meaning Aldebaran will ingress (wink out) on the bright limb of the 52% illuminated Moon, and egress (reappear) along its dark limb.

Here are some key times for ingress/egress by location (all times quoted are local and incorporate daylight saving/summer time):

Washington D.C.

Moonrise: 11:53 PM

Ingress: N/A (before Moonrise)

Egress: 12:38 AM (altitude = 8 degrees)

Boston

Moonrise: 11:22 PM

Ingress 11:57 PM (altitude = 6 degrees)

Egress: 12:41 AM (altitude = 14 degrees)

Gander, Newfoundland

Moonrise: 11:26 PM

Ingress: 1:37 AM (altitude = 20 degrees)

Egress: 2:26 AM (altitude = 28 degrees)

London

Moonrise: 11:04 PM

Ingress: 5:50 AM (altitude = 53 degrees)

Sunrise: 6:18 AM

Egress: 7:07 AM (altitude = 54 degrees)

Paris

Moonrise: 12:02 AM

Ingress: 6:53 AM (altitude = 56 degrees)

Sunrise: 7:12 AM

Egress: 8:10 AM (altitude = 57 degrees)

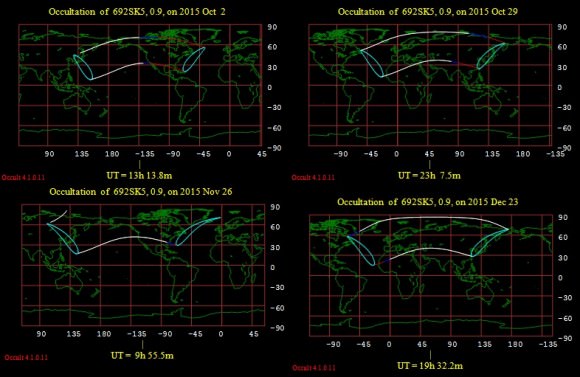

Occultations of bright stars by the Moon are one of the few times besides a solar or lunar eclipse when you can actually discern the one degree per every two and half hours orbital motion of the Moon in real time. The Moon moves just a little more than its own apparent diameter as seen from the Earth every hour. This also sets us up for four more fine occultations of Aldebaran by the Moon alternating between Europe and North America on October 2nd, October 29th, November 26th, and December 23rd.

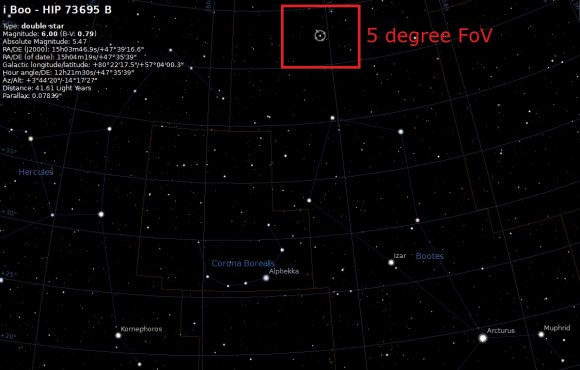

The bright stars Antares, Spica and Regulus also lie along the path of the Moon, which is inclined about five degrees relative to the ecliptic. A series of occultations of Regulus by the Moon begins in late 2016.

Fun fact: The Moon used to occult the bright star Pollux in the constellation Gemini until about 2100 years ago in 117 BC. The 26,000 year cycle known as the Precession of the Equinoxes has since carried the star out of the Moon’s path.

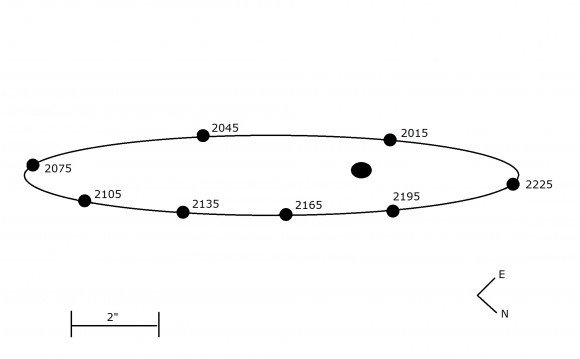

Observations of occultations — especially dramatic grazes spied right from the edge of the path — can be used to construct a profile of the lunar limb. A step-wise ‘wink out’ of a star during an occultation can also betray the existence of a close binary.

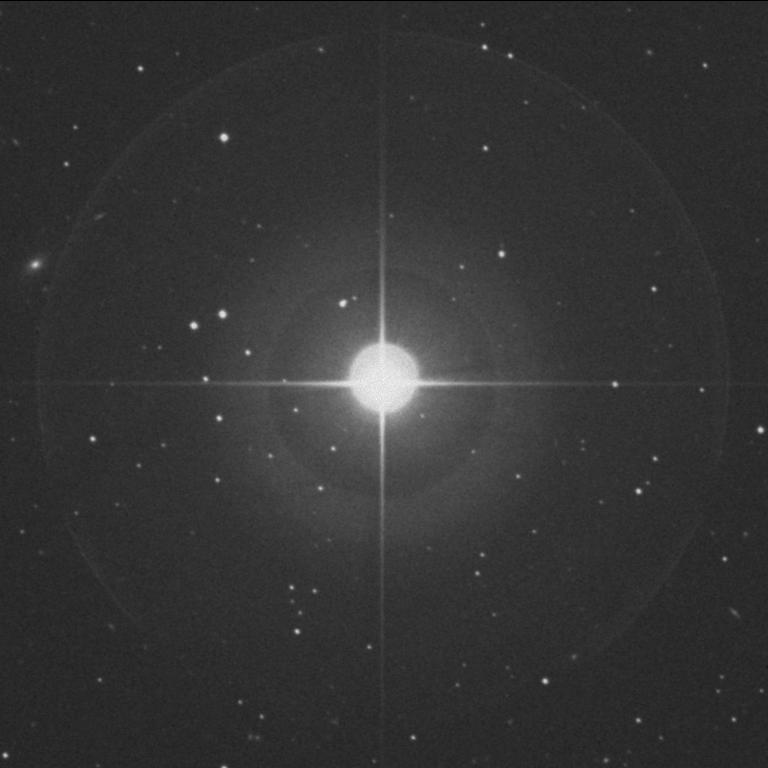

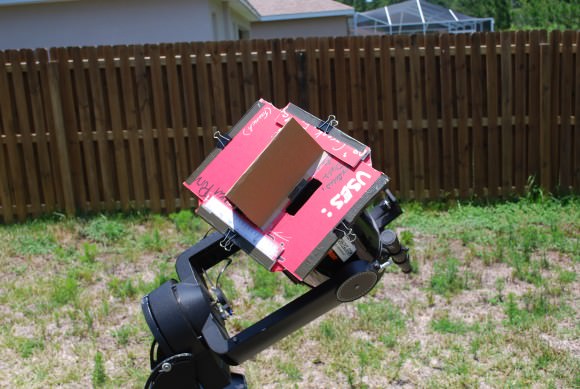

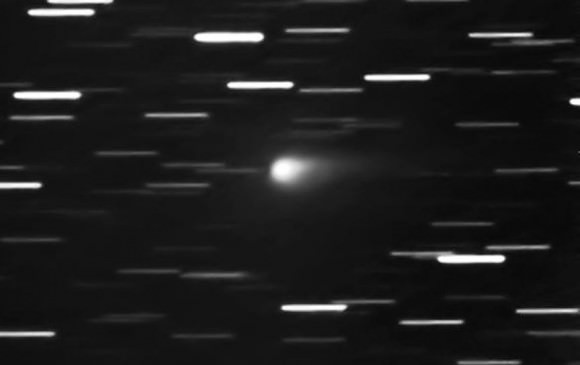

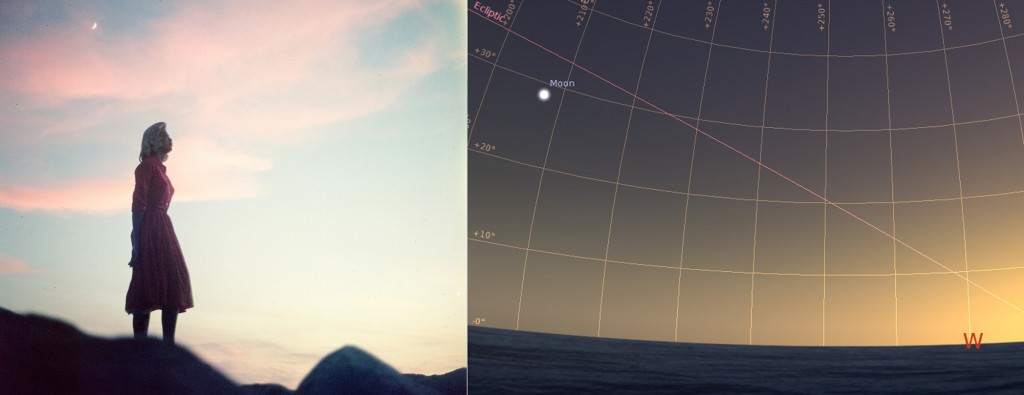

Recording an occultation of a star by the Moon is as easy as running video while shooting the Moon. The dark limb egress of Aldebaran will be much easier to record during the September 5th event than the ingress of the star against the bright limb. I typically run video with a DLSR directly coupled to a Celestron 8” SCT telescope, with WWV radio running in the background for a precise audio timing of the event. Remember, the Moon will also be transiting the Hyades star cluster as well, covering and uncovering many fainter stars for observers worldwide around the same time frame.

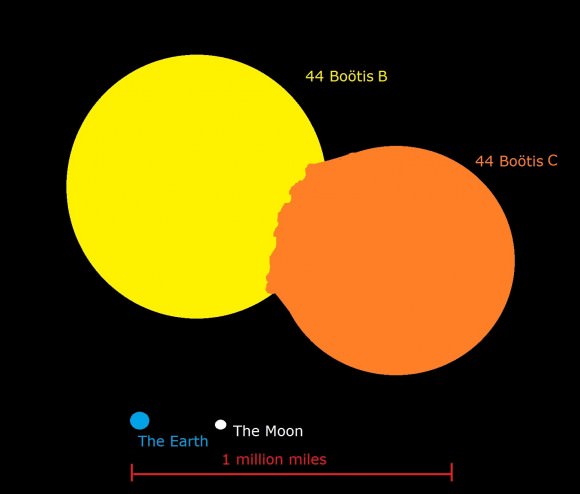

Now for the ‘wow’ factor. The Moon is about 240,000 miles (400,000 km), or 1 1/4 light seconds distant. Aldebaran is 65 light years away, and said light left the star around 1950, only to have its light ‘rejected’ during the very last second by the craggy mountains along the lunar limb. And though Aldebaran appears to be a member of the Hyades, it isn’t, as the open cluster sits 153 light years from Earth.

And watch that Moon, as it then heads for a partial solar eclipse as seen from South Africa and the southern Indian Ocean on September 13th, and a total lunar eclipse visible from North America and Europe on September 28th.

Expect more to come, with complete guides to both on Universe Today!