The venerable ‘old faithful of meteor showers’ is on tap for this week, as the August Perseids gear up for their yearly performance. Observers are already reporting enhanced rates from this past weekend, and the next few mornings are crucial for catching this sure-fire meteor shower.

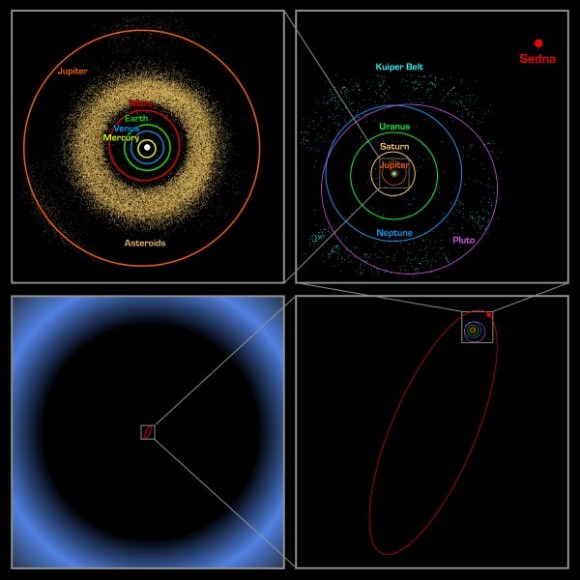

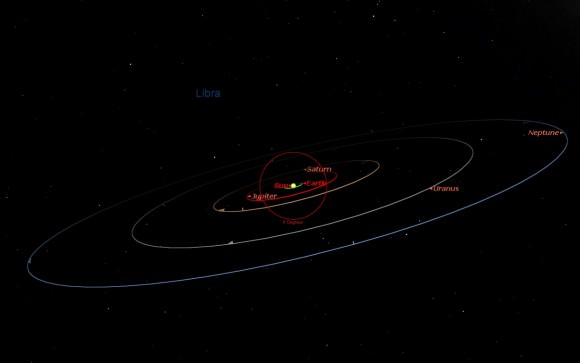

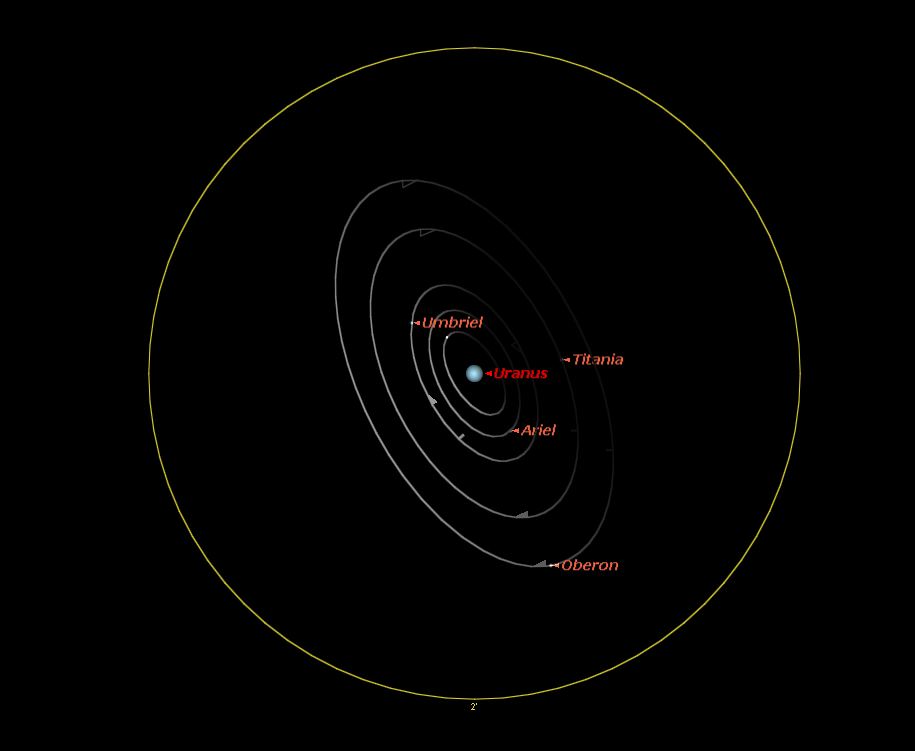

First, here’s a quick rundown on prospects for 2015. The peak of the shower as per theoretical modeling conducted by Jérémie Vaubaillon projects a broad early maximum starting around Wednesday, August 12th at 18:39 UT/2:39 PM EDT. This favors northeastern Asia in the early morning hours, as the 1862 dust trail laid down by Comet 109P Swift-Tuttle — the source of the Perseids — passes 80,000 km (20% of the Earth-Moon distance, or about twice the distance to geostationary orbit) from the Earth. This is worth noting, as the last time we encountered this same stream was 2004, when the Perseids treated observers to enhanced rates up towards 200 per hour. Typically, the Perseids exhibit a Zenithal Hourly Rate (ZHR) of 80-100 per hour on most years.

This translates into a local peak for observers worldwide on the mornings of August 12th and 13th. Comet 109P Swift-Tuttle orbits the Sun once every 120 years, and last reached perihelion in 1992, enhancing the rates of the Perseids throughout the 1990s.

Don’t live in northeast Asia? Don’t despair, as meteor showers such as the Perseids can exhibit broad multiple peaks which may arrive early or late. Mornings pre-dawn are the best time to spy meteors, as the Earth has turned forward into the meteor stream past local midnight, and rushes headlong into the oncoming stream of meteor debris. It’s a metaphor that us Floridians know all too well: the front windshield of the car gets all the bugs!

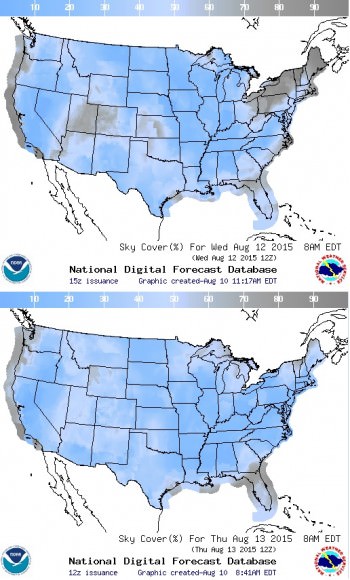

Weather prospects — particularly cloud cover, or hopefully, the lack of it — is a factor on every observer’s mind leading up to a successful meteor hunting expedition. Fortunately here in the United States southeast, August mornings are typically clear, until daytime heating gives way to afternoon thunder storms. About 48 hours out, we’re seeing favorable cloud cover prospects for everyone in the CONUS except perhaps the U.S. northeast.

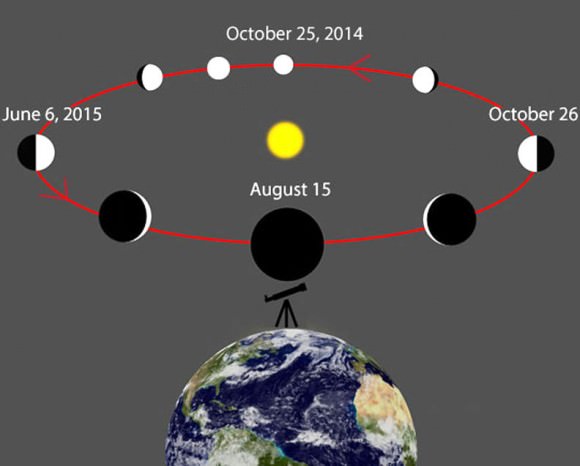

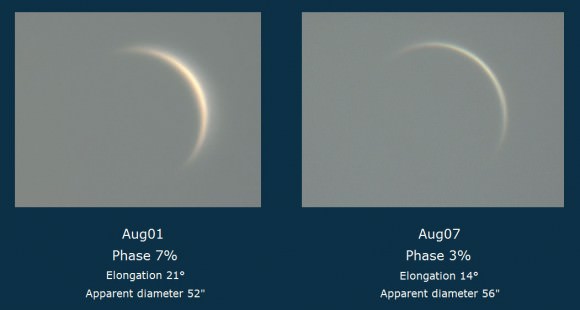

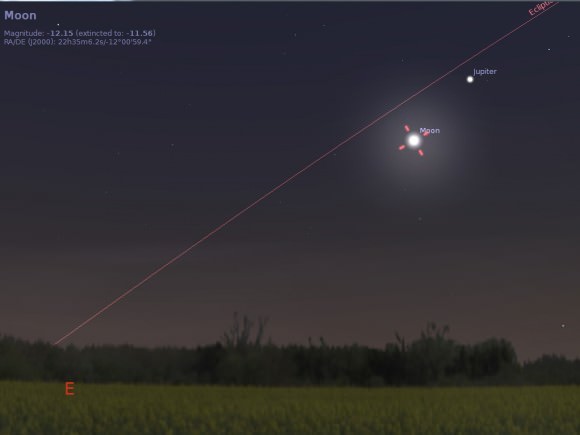

The Moon is also under 48 hours from New on Wednesday, allowing for dark skies. This is the closest New Moon to the peak of the Perseids we’ve had since 2007, and it won’t be this close again until 2018.

Fun fact: the August Perseids, October Orionids, November Leonids AND the December Geminids are roughly spaced on the calendar in such a way that if the Moon phase is favorable for one shower on a particular year, it’ll nearly always be favorable (and vice versa) on the others as well.

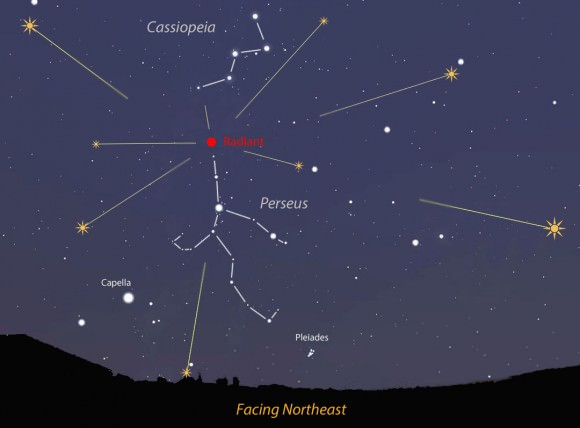

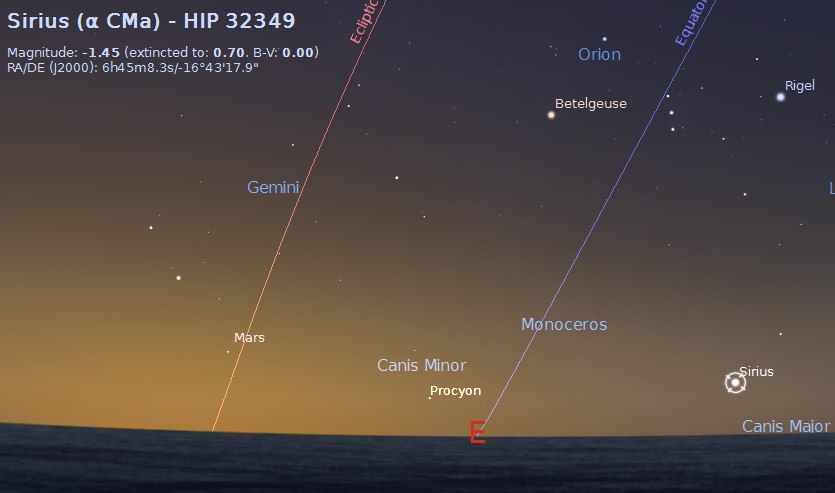

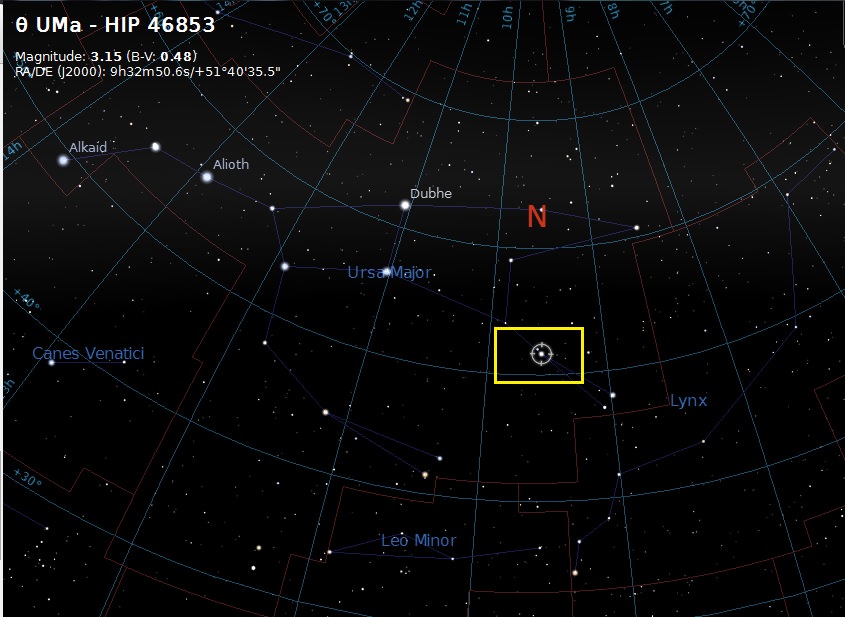

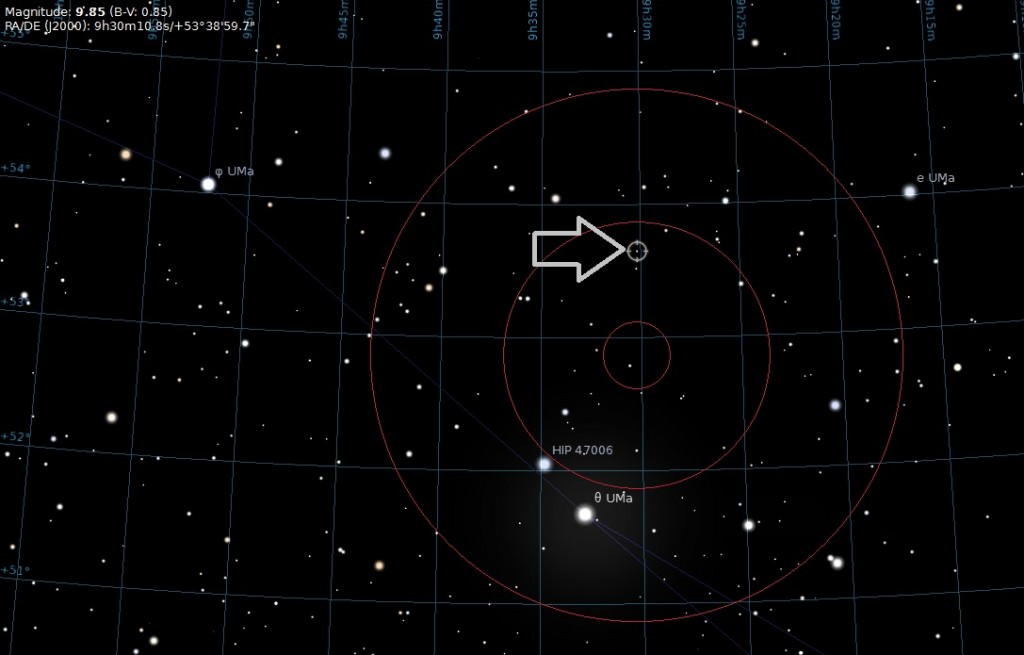

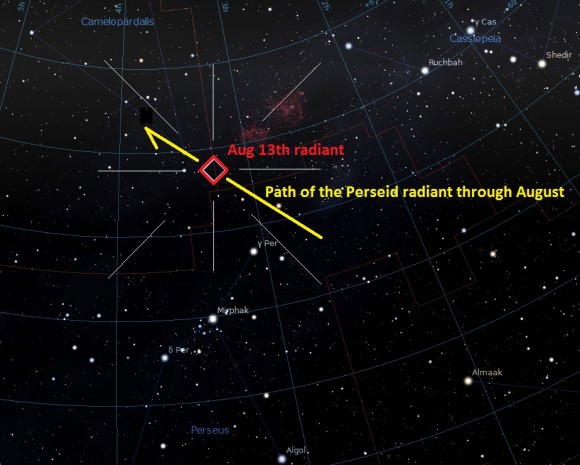

Sky watchers have observed the annual Perseid meteors since antiquity, and the shower is often referred to as ‘The Tears of Saint Lawrence.’ The Romans martyred Saint Lawrence on a hot grid iron on August 10th, 258 AD. The radiant crosses from the constellation Perseus in early August, and sits right on the border of Cassiopeia and Camelopardalis on August 12th at right ascension 3 hours 10’ and declination +50N 50.’ Technically, the shower should have the tongue-twisting moniker of the ‘Camelopardalids’ or perhaps the ‘Cassiopeiaids!’

The last few years have seen respectable activity from the Perseids:

2014- ZHR = 68 (Full Moon year)

2013- ZHR = 110

2012- ZHR = 120

2011- ZHR = 60 (Full Moon year)

2010- ZHR = 90

You can see the light-polluting impact of the nearly Full Moon on the previous years listed above. Light pollution has a drastic effect on the number of Perseids you’ll see. Keep in mind, a ZHR is an ideal rate, assuming the radiant is directly overhead and skies are perfectly dark. Most observers will see significantly less. We like to watch at an angle about 45 degrees from the radiant, to catch meteors in sidelong profile.

Imaging the Perseids is as simple as setting up a DSLR on a tripod as taking long exposures of the sky with a wide angle lens. Be sure to take several test shots to get the combination of f-stop/ISO/and exposure just right for current sky conditions. This year, we’ll be testing a new intervalometer to take automated exposures while we count meteors.

Clouded out? NASA TV will be tracking the Perseids live on Wednesday, August 12th starting at 10PM EDT/02:00 UT:

Remember, you don’t need sophisticated gear to watch the Perseids… just a working set of ‘Mark-1 eyeballs.’ You can even ‘hear’ meteor pings on an FM radio on occasion similar to lightning static if you simply tune to an unused spot on the dial. Sometimes, you’ll even hear a distant radio station come into focus as it’s reflected off of an ionized meteor trail:

And if you’re counting meteors, don’t forget to report ‘em to the International Meteor Organization and tweet ‘em out under hashtag #Meteorwatch.

Good luck and good meteor hunting!