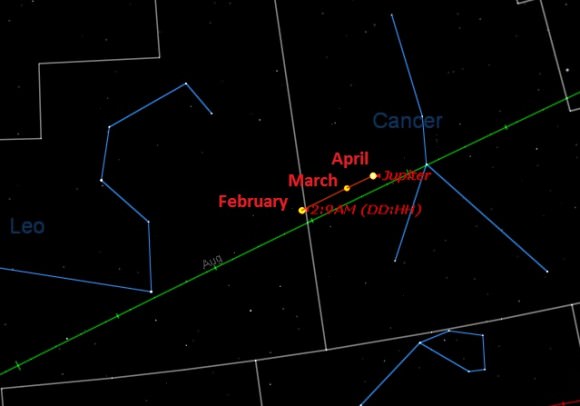

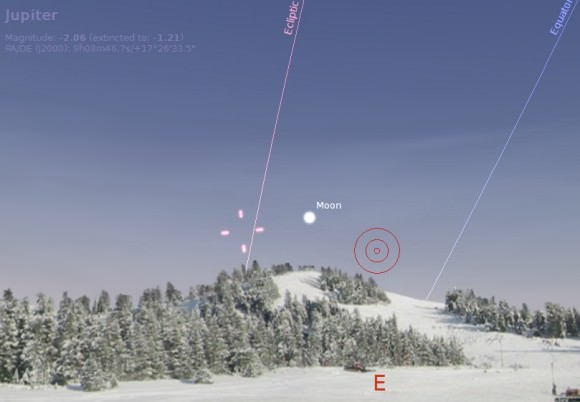

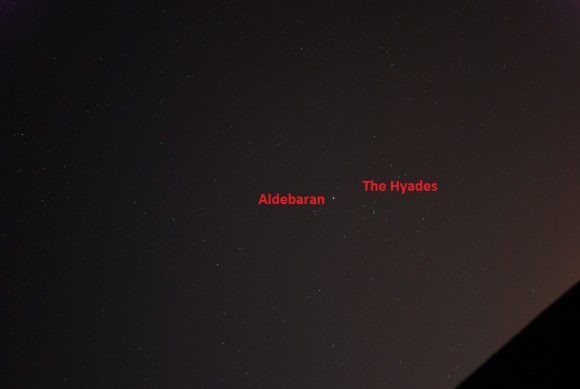

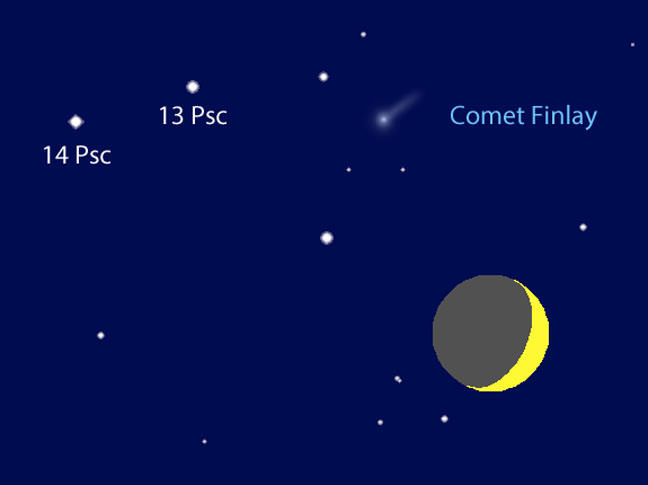

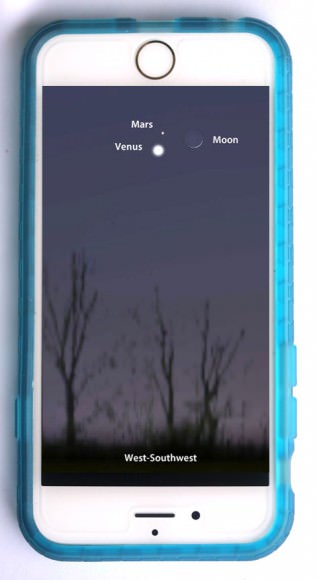

Tonight the thin, 2-day-old crescent Moon will join Venus and Mars in the western sky at dusk for one of the most striking conjunctions of the year. The otherworldly trio will fit neatly with a circle about 1.5° wide or just three times the diameter of the full moon. No question, this will catch a lot of eyes around the world. Why not take a picture and share it with your friends? Here are a few tips to do just that.

You won’t need much for an easy snapshot. In bright twilight, point your mobile phone toward the Moon and tap off a few shots, taking care not to touch the screen too hard lest you shake the phone and blur the image. The phone’s autoexposure and autofocus settings should be adequate to capture both the Moon and Venus. Mars is fainter and may only show if you can steady your phone against something to allow for a longer exposure without blurring. Assuming you use your phone in its default wide view, the Moon, Venus and Mars will form a tight, small group in a larger scene.

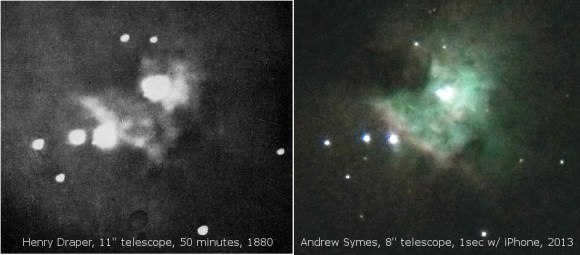

Phones provide the highest resolution in their wide setting. If you zoom in, the Moon will be bigger but resolution or sharpness will suffer. Someday phones will be as good as digital single lens reflex cameras (DSLRs) but until then, you’ll need one of these or their cousins, the point-and-shoot cameras, to get the best images of astronomical objects.

You’ll also need a tripod to keep the camera still and stable during the longer exposures you’ll need during the optimum time for photography which begins about 30 minutes after sunset. That’s when your photos will capture all three objects without overexposing the Moon and making it look washed-out. Ideally, you want to see the bright crescent contrasting with the dim glow of the earthshine.

Lucky for us, the Moon’s sharp form makes an ideal target for the camera’s autofocus. Frame an attractive landscape or ask a friend to stand in the foreground. Set your lens to its widest open setting (usually f/2.8-3.5) and the ISO (your camera’s sensitivity to light) to 800. The higher the ISO, the shorter the exposure you can use to capture an image, but high ISOs introduce unwanted noise and graininess. 800’s a good compromise. If you can manually set your exposure, start at 4 seconds.

Compose your photo and then focus on the Moon and gently press the shutter button. Check the image on the back screen. Are you on target or is it too dark? If so, double the time. If too bright, half it. As the sky gets darker, you’ll need to gradually increase your exposure. That’s when the Moon will start to wash out and the beautiful deep blue sky turn black or the color of your local light pollution. Around here, that’s pinkish-orange. I’ve got lots of orange sky photos to prove it!

All told, you can use a mobile phone to shoot from about 25-40 minutes after sunset and a DSLR from 25 minutes to 75 minutes after. If you’re shooting with a standard 24-35mm lens, keep your exposures under 20 seconds or the Moon and planets will start to streak or trail. The Rule of 500 is a great way to remember how long a time exposure you can make with any lens before celestial objects start trailing. So, 500/24mm = 20.8 seconds and 500/200mm (telephoto) = 2.5 seconds. That means if you plan to shoot the conjunction with a longer lens, you’ll need to up your ISO to 1600 or even 3200 in late twilight to get a tack-sharp, motionless photo.

Telephoto images are a bit more challenging, but they increase the size of the pretty trio within the scene. When shooting telephoto images (even wide ones if you’re fussy), shoot them on self-timer. That’s the setting everyone used before the selfie took the world by storm. Most timers are pre-set to 10 seconds. You press it and the camera counts down 10 seconds before automatically tripping the shutter, allowing you time to put yourself in a group photo.

In astrophotography, using the self-timer assures you’re going to get a vibration-free photo. If it’s cold out and you’re shooting with a telephoto, vibration from your finger pressing the shutter button can jiggle the image.

Good luck tonight and clear skies! If you have any questions, please ask.