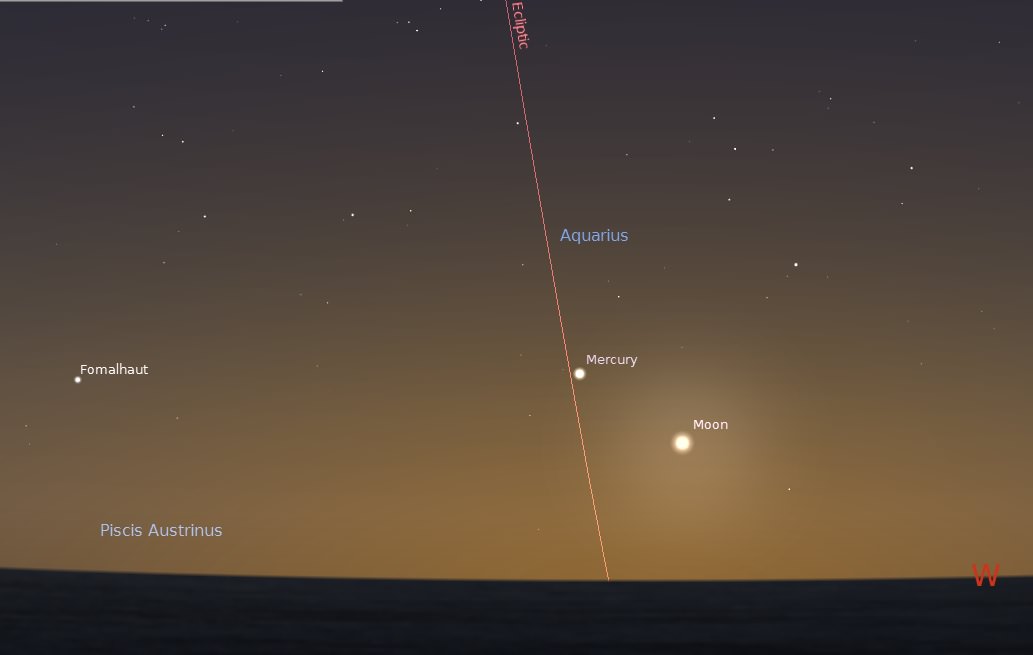

Are you ready for some lunar versus planetary occultation action? One of the best events for 2014 occurs early this Wednesday morning on February 26th, when the waning crescent Moon — sometimes referred to as a decrescent Moon — meets up with a brilliant Venus in the dawn sky. This will be a showcase event for the ongoing 2014 dawn apparition of Venus that we wrote about recently.

This is one of 16 occultations of a planet by our Moon for 2014, which will hide every naked eye classical planet except Jupiter and only one of two involving Venus this year.

An occultation occurs when one celestial body passes in front of another, obscuring it from our line of sight. The term is used to refer to planets or asteroids blocking out distant stars or the Moon passing in front of stars or planets.

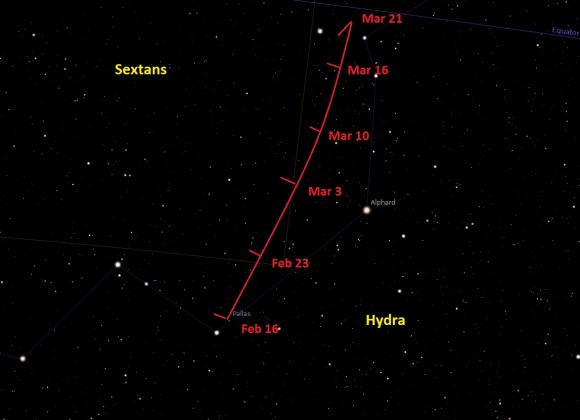

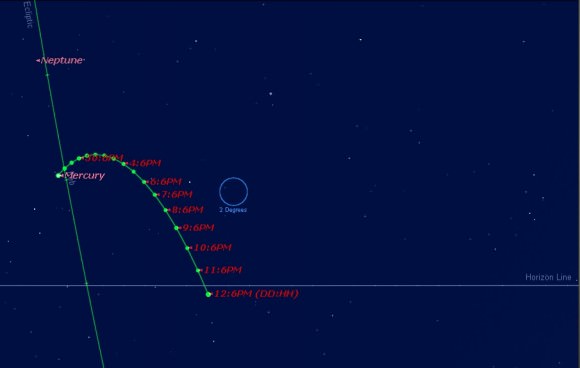

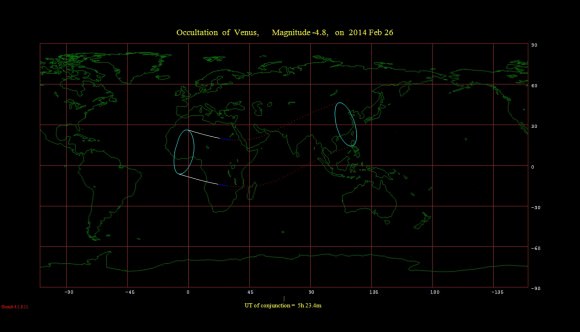

Wednesday’s event has a central conjunction time of 5:00 Universal. Viewers in northwestern Africa based in Mali and southern Algeria and surrounding nations will see the occultation occur in the dawn sky before sunrise, while viewers eastward across the Horn of Africa, the southern Arabian peninsula, India and southeast Asia will see the occultation occur in the daylight.

Observers worldwide, including those based in Australia, Europe and the Americas will see a near miss, but early risers will still be rewarded with a brilliant dawn pairing of the second and third brightest objects in the night sky. This will also be a fine time to attempt to spot Venus in the daytime, using the nearby crescent Moon as a guide. It’s easier than you might think! In fact, Venus is actually brighter than the Moon per apparent square arc second of surface area, owing to its higher average reflectivity (known as albedo) of 80% versus the Moon’s dusky 14%.

The International Occultation Timing Association also maintains a chart of ingress and egress times for specific locations along the track of the occultation.

The Moon occults Venus 21 times in this decade. The last occultation of Venus by the Moon occurred on September 8th, 2013, and the next occurs October 23rd 2014 over the South Pacific in daylight skies very close to the Sun, and is unobservable.

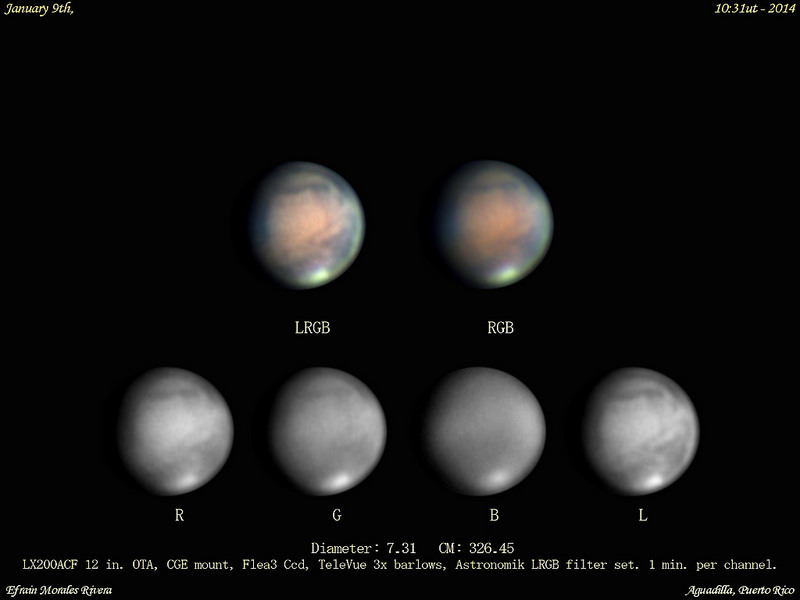

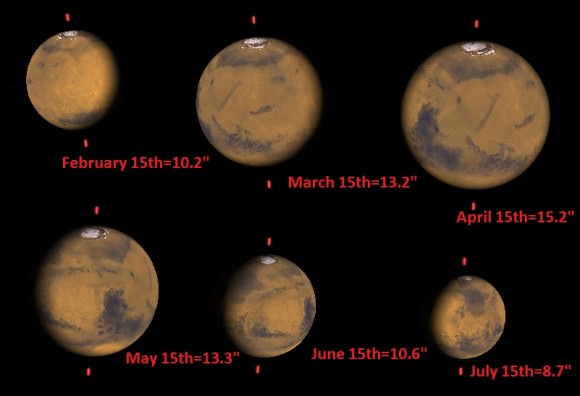

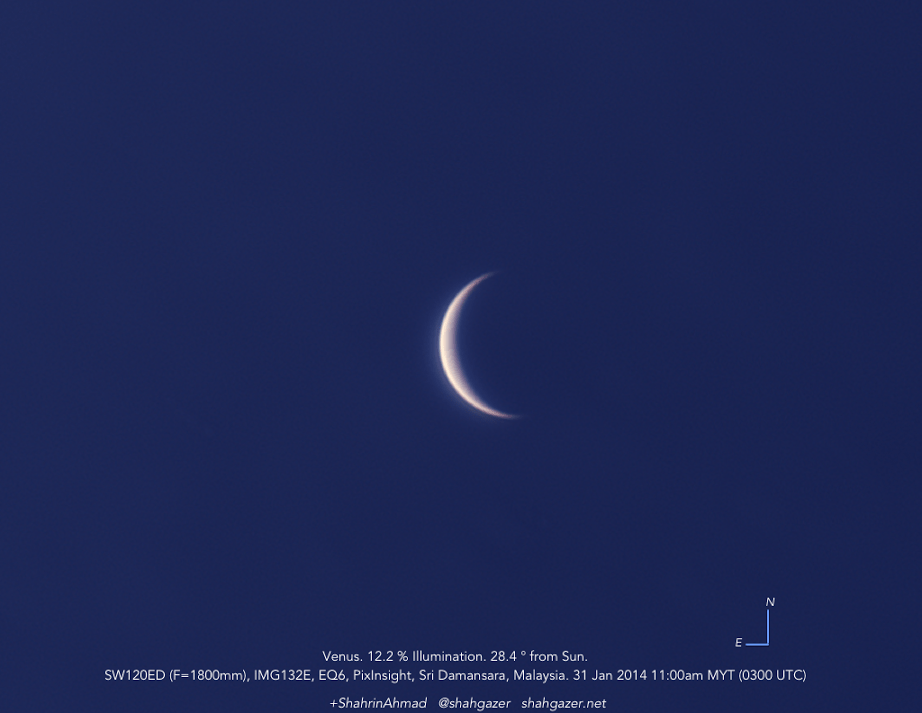

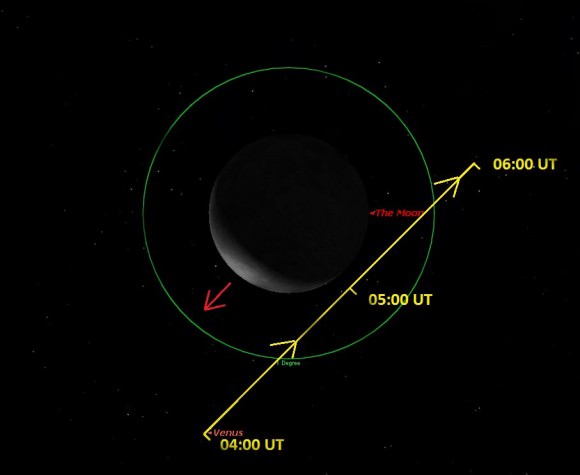

Wednesday’s event also offers a unique opportunity to catch a crescent Venus emerging from behind the dark limb of the Moon. On Wednesday, Venus presents a 34” diameter disk that is 35% illuminated and shining at magnitude -4.3, while the Moon is a 12% illuminated crescent three days from New. Fun fact: February 2014 is missing a New Moon, meaning that both January and March will each contain two!

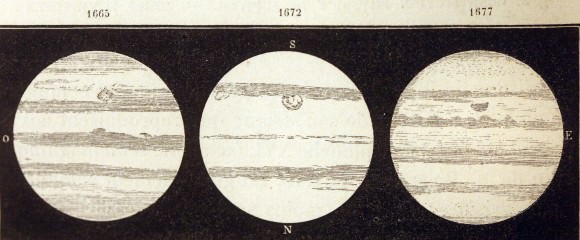

This also means that a well positioned observer in northwestern Africa would be able to see able to catch the dark limb of Venus creeping out from behind the nighttime side of the Moon against a dark sky. Such favorable occurrences only happen a handful of times per decade, and this week would be a great time to try and briefly spot – or perhaps even video or photograph – a phenomenon know as the ashen light of Venus as the dazzling crescent daytime side of the planet lay obscured by the Moon. Is this effect reported by observers over the years a fanciful illusion, or a real occurrence?

Perhaps, due to the remote location, this chance to spy and record this elusive effect will go unnoticed this time ‘round. The next chance with optimal possibilities to catch a crescent Venus occulted by the Moon against a dark sky occurs next year on October 8th, 2015, favoring the Australian outback. Anyone out there down for an observing expedition to prove or disprove the ashen light of Venus once and for all? Astronomy road trip!

This event also provides optimal circumstances as Venus heads towards greatest elongation west of the Sun on March 22nd and the Moon-Venus pair lay 43 degrees west of the Sun during Wednesday’s event. Compare this to the impossible to observe occultation this October, when the pairing is only one degree east of the Sun! The next occultation of Venus for North America occurs next year on December 7th, 2015 and will be visible in the daytime across the extent of the track except for Alaska and Northwestern Canada.

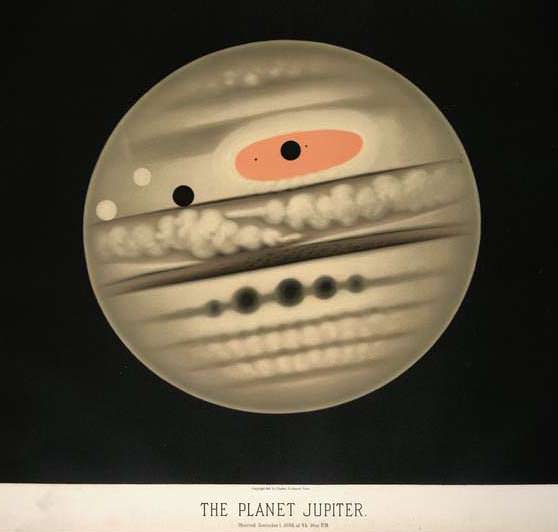

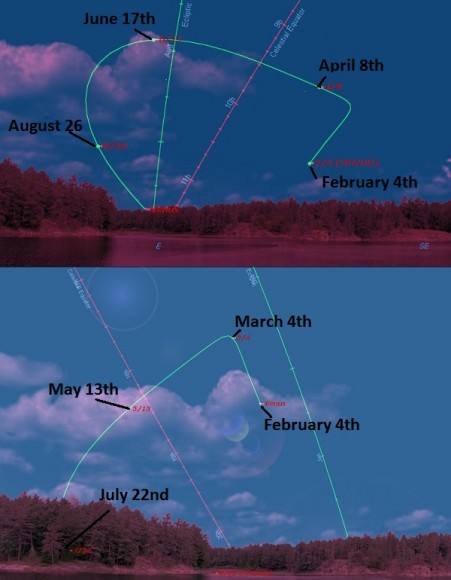

Vexillographers may also want to take note: this week’s Venus-Moon pairing will closely emulate the familiar crescent Moon plus star pairing seen on many national flags worldwide. Did an ancient and unrecorded occultation of Venus by the Moon inspire this meme? Tradition has it that Sultan Alp Arslan settled on the star and crescent for the flag of the Turks after witnessing a close conjunction after the defeat of the Byzantine Army at the Battle of Manzikert on August 26th, 1071 A.D. This tale, however, is almost certainly apocryphal, as no occultations of planets or bright stars by the Moon occurred on or near that date, and only two occultations of Venus by the Moon occurred that year. And Venus was less than two degrees from the Sun on that date, yet another strike against it. In fact, the only occultations of Venus by the Moon in 1071 occurred on June 29th and November 27th. Perhaps Arslan just took a while to decide…

Still, this week’s event provides a great photo-op to have “Fun with Flags” and capture the pair behind your favorite astronomical conjunction-depicting banner. And be sure to send those pics into Universe Today… methinks there’s a good chance of us running a post occultation photo-essay later this week!